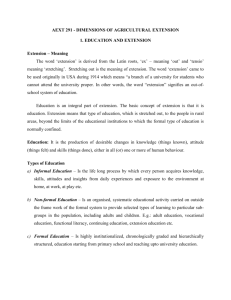

Arrested Development

advertisement