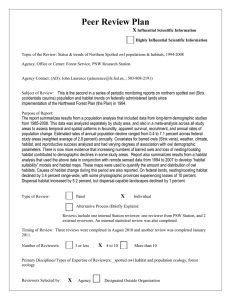

Document 11340950

advertisement

..I' Proc~edillg.r-Fir~ Eff~cls ort Rar~ and End.v.g~r~d S~cie.r and Habitats Conf~r~IIC~,NOII.1J-16, 1995. Coew d'Al~M, Idaho. to lAWF, 1997. Print~d ill U.S.A. 1 23 Effects of the Hatchery Complex Fires on Northern Spotted Owls in the Eastern Washington Cascades William L. Gaines,Robert A. Strand, and SusanD. Piper u.s. ForestService.600 Sherbourne.Leavenworth.WA98826 Tel. (509) 782.-1413; Fax (509) 548-5817 Abstract. During the summer of 1994the Hatchery Complex fIres burned 17,603ha in the eastCascadesof Washington. ThesefIres affectedthree habitatreserves and six octivity centersfor the northernspottedowl (Strix occidentalis caurina). The availability of spotted owl habitatwithin a 2.9km radiusof theseactivitycenterswas reducedby the direct effectsof the fire, (averagehabitat loss=31%, range 8%-45%)but wasalso significantly reducedbydelayedtreemortalityandinsectcausedmortality (averagehabitat10ss=55%, range10%-85%).Fewerspotted owls occuppiedand reproducedat thesesitesthan in previous years. Spottedowl habitat locatedin riparian areasor ona benchwassomewhatmorelikely to remainas fire refugia thanhabitatlocatedon mid-upperslopes.This was especiallytrue on southaspects.The availability of spottedowl habitatundercurrentand inherentfIre regimes was very dynamic acrossthe eastCascadeslandscape. Appropriate management strategiesmay includestrategically located low density fue) areascreatedto protect adjacentspottedowl habitat that 'There is a very low probabilitythat any(spottedowl habitatreserve)createdin theEastCascades subregionwill avoid catastrophicwildf"Ire over a significant JX>rtionof its landscapeover the next century." Thus the management dilema,while fire suppressionmay have increased the amount of suitable spotted owl habitat across the lanscape,it has also resultedin a greaterrisk of habitat loss due to catastrophicfIres (Agee and Edmunds 1992, Buchananet al. 1995). Managementof theselandscapes must considerthe short-termhabitatneedsof the spotted owl and the risk associatedwith standreplacementfires. Important in the managementof these landscapesis understandinghow fire affectsspottedowls and theirhabitat. Our objectiveswere to quantify,as muchas possible, the effectsof the HatcheryComplexfires on spottedowl habitat.occupancyrates,and reproduction. In addition, the future risk to additional owl sitesand JX>ssible managementstrategieswill re presented. Study Area Introduction Firesare a naturaleventwithin the eastsideCascades ecosystems(Agee 1994),however,flre suppressionand logging have contributedto higher fuel loadingsthat can lead to higher fIre intensity than would have inherently occurred(Agee and Edmunds1992). The fIres of 1994 were a dramatic exampleof this. Areasin which the inherentdisturbanceregime would havebeenlow to moderateintensityand high frequencyfifes,burnedasmoder~ ate to high intensity stand replacementfIres. Severalof thesefIreswerepartof theHatcheryComplexthatincluded the Rat, Hatchery,Eightmile, BlackjackI and Blackjack II fires. In total thesefires burnedabout17,603ha. These fIres burned within threeareasthat have been identified as Late-SuccesionalReserves(USFS 1994and 1995). Theseareashave management objectivesto provide habitat for late- successionalassociatedspecies,including the Threatened northern spotted owl (Strix occidentaliscaurina). Agee and Edmunds(1992)stated This studywasconductedon theLeavenworthRanger District. WenatcheeNational Forest, located on the east sideof the Cascadesof Washingtonstate(Figure 1). Elevationsrangefrom 650 metersto 1300meters. The study area is composedof ponderosapine (Pinus ponderosa) plant associationsat lower elevations,and Douglas-fIr (Pseudotsuga menziesil) andgrandfir (Abiesgrandis)plant associationsat the mid-elevations. Disturbances,suchas fIre, have beenshownto havea significantinfluence on the vegetationpatternsand processesof eastCascadelandscapes(Gastet al. 1991,Agee 1994,Johnsonet al. 1994,Harrod et al. 1996). Prior to fIre suppression, fire occurredat relatively frequentintervals within east~ forests(AgeeandEdmunds1992). For example,within the JX>nderosa pine and dry Douglas fIr plant seriesfire occurredat intervalsof 10 to 25 years resulting in a foreststructure largely compnsedof open park-like ponderosapine forests(Agee 1991 and 199.4). Fires in theseforestswere usuallyof low to moderateffitensity. --- . 124 Gaines.W1 Sb'and.R.A..andPipeJ', S.D. --""'" ;J -,.o\~( -"", , " ;_:~- -1 T~0 .1- t ~- e ! '""~ --u- 0 - ~.. -_. 20- ~-"""~ Figure 1. Vicinity mapof the Ratand HatcheryFires. -Effects of the Hatchery Complex Fires on Nothern Spotted Owls -125 Fire suppression and logging have signficantly altered these forests. With the advent of effective fire supression technologies, fIre frequency within these forests was significantly reduced (Agee and Edmunds 1992). In addition, logging practices until about 1950 often focused on removing the most fire tolerant species,the large ponderosa pine (Wellner 1984). The end result is that eastside forests are now composed of more shadetolerant tree species, are less fIre tolerant, are at higher densities, and are more prone to large scale high intensity fIres (Agee and Edmunds 1992, Camp 1995). Data Analysis A linear correlation analysis (Zar 1984) was completed to determine if there was a relationship between site status and the degree to which habitat was affected by the fIres within a 0.8 kIn and 2.9 kIn radius. A Chi-Square Goodness of Fit test (Zar 1984) was used to determine if Metbods there was a significant difference between habitat burned vs habitat available at several lOCationson the burned landscape. Habitat Inventory Inventories of spotted owl habitat were completed from aerial photo-interpretation followed by field verification. These data were then loaded into MOSS geographic information system for habitat analyses. Habitat inventories were completed prior to the fITe,immediately post-fIre, and one year after the fITesoccurred in order to measure habitat changes over time. Suitable habitat was defined as having at least a 60% canopy closure presence of numerous snagsand several down logs, and two or more canopy layers. The habitat mapping resolution was 0.8 ber of young. Surveys and site monitoring were accomplished through a cooperative effort between the U.S. Forest Service, National Council on Air and Stream Improvement, and Natapoc Resources. Persistence a/Spotted Owl Nest Sites Camp (1995) presents a probability model for the development of late-successional fIre refugia under an in. herent disturbance regime for the eastern Cascade mountains. Because spotted owl nesting habitat has been shown to be associated with these late- successional conditions (Buchanan et aI. 1993, Buchanan et aI. 1995) this model was used to show the potential for a fIre under an inberent disturbance regime, at the 28 known nest sites on the Leavenworth Ranger District. M. Once habitat maps were developed anadditional analysis was condocted to describe landscape features for habitat that was within the fITe perimeter but remained suitable following the fITe. This analysis was completed for all habitat within a 2.9 km radius around three of the six fITe affected activity centers. A spotted owl activity center is the location in which there was a resident single, pair or nest site (USFS 1991). These three spotted owl activity centers were selected because they were distributed across the burned landscape, they were the most extensively affected, and there was no overlap in habitat within the 2.9 km radius. This information was developed to determine if habitat at particular landscapelocations burned at proportions equal to, greater than or less than was available within the three activity centers. Habitat was classified into one of the following categories: north aspect (>270 to 89 degrees), south aspect (>90 to 270 degrees), riparian, v~ey (>300m wide), bench «10% slope and >6 ha), and mid-upper slope. Spotted Owl Inventories The Region 6 spotted owl survey protocol was followed (USFS 1991). During 1995, spotted owl activity centers were surveyed regardless of how extensive the habitat was changed as a result of the fIres. Sites were monitored to determine if spotted owls were present, and if so, their status: single, pair, or reproductive pair. If ed be reprod uctIve, . adA: spotted owls were determm to wtional monitoring was conducted to determine the num- . . Results and D&ussion Habitat Availability The availability of suitable spotted owl habitat within a 2.9 kIn radius of the six affected activity centers prior to the fIre, immediately following the fIre and one year post-fIre are shown in Table 1. The average amount of habitat loss that occurred within a 2.9 kIn radius was 31 :0 and ranged from 8% to 45%. The average amount ofhabltat lost within a 2.9 kIn radius as of one year after the fIre was 55% and ranged from 10% to 85%. ... These data show that a considerable reductIon m habltat occurred as a result of the direct effects of the fIre, however, additional habitat reductions occurred well after the fIres were out. This occurred because trees darnaged but not directly killed by the fires eventually died. Table 1. Habitatavailabilitypre-fire,IX>st-flre, andoneyearIX>stfire within a2.9 km radius of sponooowl activity centers(n=6), HatcheryComplexFires. SileNo. I 2 3 4 5 6 ~-fire (Ita) 691 493 512 604 618 377 Post-fire (Ita) 463 454 399 344 420 208 1 Yr Post-fire (Ita) 342 446 114 3~; 171 . 126 Gaines,W L., Sb'and,R.A., andPiper, S.D. In addition, some b"eeSthat survived the flTeShave been killed by increasedinsectactivity. It is expectedthatthis nend will continue as insectpopulationsincrease,however the extent is not yetknown. The resultsof the analysisto detennineif suitablehabitat at various locations on the landscapeburned in proportion to its availability are shown in Figures 2 and 3. Habitatlocated on north aspectsand within riparian areas burnedless than available, thoughnot statisticallydifferent(p>O.O5). Habitat on north slopeslocatedon a bench burned at proportions equal to it's availability. Habitat on north slopeson the mid-upperpart of the slopeburned at levels slightly greaterthan available, but not statistically different than expected(p>O.O5).On southslopes habitat located on a benchburnedat levels that were significantly less than expected(p<O.O5). Habitat located on southslopesand onthe mid-upperportion of the slope burned at proportions greaterthan available, but not at levels significantly different than expected(p>O.O5). SiteStatus The resultsof the spottedowl surveys at the six flIe affectedactivity centersare shownin Table 2. Four of the six siteswere not occupiedduring 1995. At one of thesesitesthe flfe ovenook the activity centervery rapidly and at extremelyhighintensity. It is likely that these owls did not survive the flfe, and their octivity centeris likely no longercapableof supportingan owl pair. Habitat at an additional site wasreducedto levels that make it unlikely that it could supportspottedowls. This sitewas not occupiedin 1995.Fewerof theseactivity centerswere occupied in 1995 than at any time during the previous four years. In addition, only one site was reproductive, also the lowestlevel comparedto the previous four years. Site Statusand Habitat Availability There was no correlation betweenthe habitat available within a 2.9 km radiusone yearpost-fire and the site status(alpha=O.O5, p>O.O5).Therewas, however,a cor- r. 00 so 4 3 1~%Bumed I 10 % Available! 2 I Riparian VaJley Bench Mid-Upper Landscape Feature Figure 2. Proportion of spon~ owl habitat that burned vs that available at various locations on north astx:Cts,Hatchery Complex ftreS.~ . -Effects of the Hatchery Complex Fires on Nothern Spotted Owls -127 30 25 20 15 I~% Burned! l.o %Available! I 5 Riparian Valley Bench Mid-Upper Landscape Feature Figure 3. Proportionof SJX>tted owl habitatthat burnedvs that availableat variouslocationson southaspects, HatcheryComplexfires. Table 2. Statusof SJX>tted owl activity centersfor four yearsprior to the Hatchery Complex fires and oneyearfollowing. Stanu 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 However, reproduction during 1994 was also quite low, and as shown in Table 3, 1995 was overall a low year for reproduction. Reproduction,.at leastone yearpost-f]1'ewas . not reduced much below preVIously reported low years. No~mt 5~ Single Pair Reproductive 5~ No. sites 4 25% 25% 5~ 4 2Mo 2Mo 60'10 5 17% 33% 17% 33% 66% 6 6 17% 17% Spotted Owl Nest Sites and Inherent Fire Regime A total of 28 nest sites on the Leavenworth Ranger District were evaluated using the fife refugia model developed by Camp (1995). The results of this evaluation are shown in Figure 4. Two (7%) of the nest sites were in relation between site status and the amount of habitat reroaming after the fire within a 0.8 mile radius (alpha=O.05, Table 3. Comparisonof II young/site at spotted owl activity centersaffactedand not by the HatcheryComplexfires. p<O.?5). As the availability o~ habitat increased so did the sIte status (no presence bemg low status and repro- Sile Data ductive pair being the highest status). Affcctedby fires CN young/site) Reproduction Data from all owl sites on the Leavenworth Ranger District were used to compare reproduction at burned vs unburned sites. These data are shown in Table 3. The 1995 season (one year post burn) was lower than any of the previous four years at the sites affected by the fifes. No. sites 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995- 0.6 1 0.8 0.3 0.2 5 5 6 6 6 Not affected fy fires CN young/site) 0.9 1.3 .03 1.8 0.3 No. sites 1315 15 14 17 ~ .;.:4":;, 128 Gaines,W.L., SU'and, R.A., andPiper, S.D. locations wheretherewas only a 2% probability of them remaining as fire refugia underan inherent fire regime. Fourteen(50%) of the sites occurredat a position on the landscapein which therewas a 10% probability of them remaining as fire refugia under an inherentdismrbance regime. Eleven (39%) of the nestsitesoccurredat locations in which there was a 19% probability, and 1 (4%) was at a location in which therewas a 51% probability of them remaining as fire refugia. This assessment exarnplifies the dynamic nature of spottedowl habitat acrossa landscapein which fire played its inherentrole. This is especiallytrue on forests on the eastside of the Cascadeswhere relatively dry conditions resultedin frequentfifes (Agee 1994). Conclusions Becausedatafrom only one seasonhasbeencollected up to this point, conclusionsmustbe maevery cautiously. Additionalmonitoring of thesesiteswill occurin succeeding yearsand datamay supponthe fmdings madein this initial evaluationor it may provide new insights. However, at this point the following observationsabout the effectsof the HatcheryComplexfires on spottedowls and their habitathavebeenmade. The fifes reducedthe availability of spottedowl habitat around six activity centers. The initial direct reduction causedby the fife was not an accuratereflection of the total affectson habitatavailability. Fire damagedtrees continuedto die,andincreasedinsectactivity contributed to the total reductionin spotted owl habitat within the burnedlandscape. Habitatlocatedwithin riparian areasand on a bench is somewhatmore likely to remainas suitable following a fife vs habitat locatedon the mid-upper slopes,especially on southslopes.This information shouldbe useful in the developmentof managementplans for habitat reserves. In the six fife affectedactivity centerstherewasa decreasein the numberof reproductivepairs andan increase in thenumberof sitesnotoccupied.Direct mortality likely occurredat one of thesitesasa result of rapid and intense fife. S 1mNo. of nest sites 0 % of nest sites 2% 10% 19% 51% Probability of Becoming fire Refugia Figure 4. Persistence of sjX>ttedowl nest sites (n=28) using the Fire Refugia model (Camp 1995). Hatchery Complex fires.~ . ..'""'i.-_;_,,~Si;;A!':';' -Effects of the Hatchery Complex The availability of spotted owl habitat across the eastem Cascades landscape appears to have been very dynarnic under inherent disturbances (Camp 1995). This is an sb"ategies important for consideration habitat reserves. when developing The flIe refugia management model d C eveloped by ~dy s~ould (1995) be usef~.m m the hIghest .,.. ...ow amp and on Nothern u.s. from strategies of sustammg habitat reserves ters (Agee fuel fire fuel loading 1992). areas could of adjacent climax and may be neccessary and Edmunds density tection of Wellner, owl habl- ponderosa to protect owl habitat pro- and restoration of may imp~t Servlce, . P 0 rtl an d, Or . 1984. History proiX>Sed nonhem SIXI~ and status of silviculblral Douglas-fir manage- and grand flI forest types. glas-flI and grand flI forest types. Wa. State Univ. Coop. Ext., low dual objectives: that for surveymg Pages 3-10 in D.M. Baumgarter aro R. Mitchell, Eds. SilviculblIal management strategies for pests of the interior Dou- cen- located C.A. F ment in the interior within activity Strategically accomplish spotted tree density -129 1991. Gwdelines activities ls .orest USDA tal Management Owls of the northern spotted owL USDA Forest Service, Portland. U.s.Or.Forest Service. thIS that resu~t spotted Spotted Forest Service. 1994. Record of Decision for the managementoflate-successional associated species within the range .management mlonnauon developl.n~ probabIlity Flres Pullman, Zar. J.H. Wa. 1984. ~iostatistical Englewood Analysis. Prentice-Hall, Cliffs, N.J. pine. References Agee. J.K. 1994. ~systems GI'R-320. Fire IIxi weather disturbances in terresrrial of the Eastern Cascades. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNWUSDA Forest Service, PNW Station. Portland, Or. 52pages. Agee. J.K.,1Ixi R.L. Edmunds. 1992. Forest protection guidelines fur the northern S}X)tted owL Pages 181-244 in U.S. Dept. of Jntaior, R~very plan for the northern spotted owl-fmal draft. Vol. 2 U.S. Govt. Print. Off.. Washington. D.C. Agee. J. K. 1991. Fire histOry of Doug!as- fir forests in the Pacific Northwest. Gen. Tech. Rep. PNW -GTR-285. USDA Forest Service, PNW Research Station. Portland, Or. Budlanan. J.B.. L.L. Irwin. and E.L. McCutchen. 1995. WithinItaI¥i nest site selection by SIXltted owls in the eastern Washington Cascades. J. Wildt Manage. 59(2):301-310. Bucl1anan, J.B., L.L. Irwin, and E.L. McCutchen. 1993. Char~teristics ~, of spotted owl nest trees in the Wenatchee National Forest. J. Ra~ Res. 27(1):1-7, A.E. 1995. Predicting late-successional physiography and topography. ~ fire refugia from Dissertation. Seattle, W L Gist. W.R.. D. W. Scott, C. Schmitt, D.Clemens, S. Howes, C.G. Johnson. Jr., 8I¥i others. 1991. Blue Mountains report: new perspectives Univ. Wa., in forest heaTh. USDA forest health Forest Ser- vice. Harrod, R.J., W.L. Gaines, Biodiversity in the Blue R.I. Taylor, and others. 1996. Mountains. In R. Iaindl and T. Quigley. Eds. Search for a solution -sustaining the land, people and ~nomyofthe Blue Mountains, a synthesis of our knowledge. USDA Forest Service, Blue Mountains Resources Institute, LaGrande, Or. Johnson. C.G.. R.R. Clausnitzer, P.J.Mcl1ringer. 1994. Biotic Gen. Tech. aJ¥i abiotic Rep. guidelines Eastan PNW -GTR-322. for the Wenatchee Washington andC.P .Oliver. processes of eastside ecosystems. USDA PNW Research Station. 50 pages. U.s. Forest Service. 1995. Late-Successional IIxi Natural Forest Service, Reserve: Standards National Forest in the Cascades IIxi Yakima Provinces. USDA Forest Service, Wenatchee National Forest, Wenatchee, Wa. . Inc., Proceedings: Ar~~nference on T10 NA L ASSOC IAn 0 N ... Washington Foundation for the Environment r" D~:D ARE , , Proceedings: First Conference on Fire Effects on Rare and Endangered Species and Habitats Coeur d' Alene, Idaho November, 1995 Dr. Jason M. Greenlee Editor Conference organizer: ASSOC IAn 0. OF lAND ARE Co-sponsors: International Association of Wildland Fire Wildlife Forever Washington Foundation for the Environment Dr. Jon Keeley Colorado Natural Heritage Program The Nature ConserVancy U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. NIFC Abundant Ufe Seed Foundation Montana Prescribed Fire Services, Inc. Environmental & Botanical Consultants USDA Forest Service (Reg-G) Proceedings courtesy of: ~~ & .Dedicated Ildhfe Forever Washington Foundation for the Environment to preserving and enhancing our state's environmental heritage by supporting educational and Innovative projects