by (1986) John Nicholas Brown A.

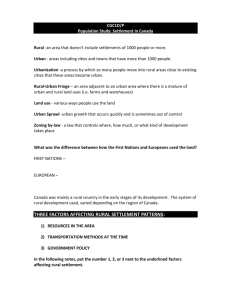

advertisement