180 Walker, G.W., and Duncan, R.A. (1989). Geologic map of the... quadrangle, western Oregon. U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Investigations Series

advertisement

180

Walker, G.W., and Duncan, R.A. (1989). Geologic map of the Salem 1° by 2°

quadrangle, western Oregon. U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Investigations Series

Map I-1893.

Wallace, P. J., and Carmichael, I.S.E. (1992). Sulfur in basaltic magmas. Geochimica et

Cosmochimica Acta, 56, 1863-1874.

Wallace, P.J., and Carmichael, I.S.E. (1994). S speciation in submarine basaltic glasses as

determined by measurements of SKD X-ray wavelength shifts. American Mineralogist,

79, 161-167.

Wells, R.E. (1990) Paleomagnetic rotations and the Cenozoic tectonics of the Cascade

arc, Washington, Oregon, and California. Journal of Geophysical Research, 95, 1940919417.

Winther, K.T., Watson, E.B, and Korenowski, G.M. (1998). Magmatic sulfur compounds

and sulfur diffusion in albite melt at 1 GPa and 1300-1500°C. American Mineralogist,

83, 1141-1151.

181

CHAPTER 5

GEOCHEMISTRY OF 2004-2005 MOUNT ST. HELENS ASH: IDENTIFICATION

AND EVOLUTION OF THE JUVENILE COMPONENT

Michael C. Rowe

Carl Thornber

Adam J.R. Kent

This manuscript has been submitted for publication as a U.S. Geological Survey

Professional Paper

182

ABSTRACT

Petrologic monitoring of volcanic ash is often utilized for identifying juvenile

volcanic material and observing changes in the composition and style of an eruption.

During the 2004-2005 eruption of Mount St. Helens, identification of juvenile material in

early phreatic explosions was complicated by a significant proportion of 1980-1986 lava

dome fragments and glassy tephra in addition to older lithic fragments. Compositions of

glass, mafic phases, and feldspars and groundmass textures are correlated in an attempt to

identify juvenile material in early phreatic explosions and differentiate between various

methods of producing and distributing ash. Clean glass in the ash is dominantly

correlated with older eruptive events and is not particularly useful for identifying juvenile

compositions. High Li concentrations in feldspars provide a useful tracer for juvenile

material and indicate an increase from 10% to 28% juvenile material between October 1,

2004 and October 4, 2005 prior to the emergence of hot dacite on the surface of the crater

on October 11, 2004. The presence of high Li feldspars out of equilibrium with the

groundmass and bulk dacite early in the eruption is also suggestive of vapor enrichment

to the initially erupted dacite. If excess vapor was indeed present, this may have assisted

in triggering the recent eruption. Textural and compositional comparisons between dome

collapse events, vent explosions, and dome fault gouge indicate that the fault gouge is the

likely source of ash for both types of events. Comparisons between vent explosions and

dome collapse events suggest that the fault gouge and new dome were initially very

heterogeneous, becoming increasingly homogeneous by early January 2005.

183

INTRODUCTION

The phreatomagmatic eruption on October 1, 2004 was the first of five such

events between October 1-5, 2004 which preceded the emergence of hot dacitic material

on the crater floor of Mount St. Helens on October 11, 2004. From October 5, 2004

through December 2005, two phreatic explosions and numerous dome collapse events

have sent volcanic ash over the crater rim (Scott et al., in preparation). Volcanic ash

provides a means by which changes in eruptive behavior can be observed in near real

time and, in some cases, may prove to be a precursor to changes in volcanic activity

(Taddeucci et al., 2002). Monitoring of volcanic ash is often conducted because it can be

collected safely, easily, and at low cost. Also, because the erupting crater/vent is not

always visible or accessible, volcanic ash may provide the only petrologic evidence for

the onset of, or changes in an eruption.

Juvenile magmatic glass has been observed in tephras prior to extrusion of

lavas/domes or before large magmatic eruptions (Watanabe et al., 1999; Cashman and

Hoblitt, 2004). Monitoring of glass compositions in volcanic ash has also identified

multiple magmatic components in eruptions, and has recorded compositional changes

over the course of a single eruption (i.e. Swanson et al., 1994; Swanson et al., 1995,

Pallister et al., 1992, Schiavi et al., in press). At Mount St. Helens, there are several

factors related to previous eruptive events that complicate the ash story, making

petrologic monitoring of volcanic ash enigmatic. Lava dome growth from 1980-1986

generated a thick cap (~250m) of dacitic lavas over the preexisting conduit. In addition,

crater-filling breccia and tephra from the May 18, 1980 and prior eruptions may underlie

184

the 1980-86 lava dome for 500m or more (Friedman et al., 1982). Phreatomagmatic

eruptions are therefore likely to have a significant proportion of older Mount St. Helens

material. Evaluation of ash is further complicated by processes related to mechanical

sorting, which occurs as a function of distance from the vent and requires consideration

of sampling location and wind velocity when comparing ash samples (e.g. Houghton et

al., 2000; Sparks et al., 1997).

Petrologic studies of older Mount St. Helens tephras provide a basis for

comparing products from the 2004-2005 eruption. Published glass analyses from 19801982 tephra and dome samples demonstrated trends of increasing crystallinity and

decreasing water content over the course of the eruptive period, with lower water likely

associated with progressively lower volume and intensity post-May 18 explosive

eruptions (Melson, 1983; Sarna-Wojcicki et al., 1982b). Textural comparisons of the

May 18, 1980 blast material with precursory eruptions indicate the appearance of juvenile

material as early as two months prior to the big blast and that the juvenile component was

reflected by ash particles with either glassy or microcrystalline matricies, characteristic of

shallow crystallization (Cashman and Hoblitt, 2004). The study by Cashman and Hoblitt

(2004) is significant in that it identifies the need to consider crystalline material in

addition to glassy fragments as potentially juvenile and provides a textural comparison

for current eruptive products. Juvenile material, as defined here for the 2004-2005

Mount St. Helens eruption, refers to material erupted hot with textural and geochemical

characteristics of the earliest new dome material (SH304-collected November 4, 2004)

and later dome samples.

185

Studies of volatile element concentrations in tephras have been utilized to identify

evidence for magmatic degassing associated with explosive events before and after May

18, 1980 (Thomas et al., 1982; Berlo et al., 2004). A 210Pb excess and a large Li spike in

plagioclase feldspars (up to ~23 Pg/g) in the 1980 cryptodome, followed by significantly

lower Li concentrations in the May 18 climatic eruption and following eruptive events,

led Berlo et al. (2004) to propose that anomalously high Li concentrations were the result

of vapor enrichment, originating from a deep source, to shallowly stored/stalled magma.

The goals of this study of 2004-2005 Mount St. Helens ash are to 1) identify

juvenile eruptive material in phreatomagmatic events associated with the reactivation of

Mount St. Helens, and 2) combine textural and geochemical observations to distinguish

between the processes and products of ash generation, including a comparison between

dome collapse events and phreatomagmatic vent explosions. Accomplishing these goals

requires a detailed examination of the textures and geochemical characteristics of the

erupted ash samples in comparison to dome rock petrology and geochemistry provided by

other studies (Pallister et al., in preparation; Kent et al., in preparation; Thornber et al., in

preparation).

METHODS

Sample Collection

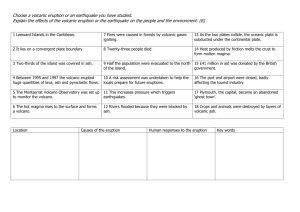

Following the October 1, 2004 phreatomagmatic eruption, 27 ash collection

stations were established around the perimeter of Mount St. Helens (Fig. 33). Ash

samples collected prior to the establishment of stations were made from relatively clean

186

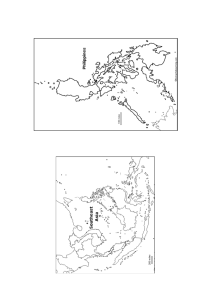

Figure 33. Locations map of ash collection stations, JL-1 and A02 to A27, established

around Mt. St. Helens, Washington. Samples collected from locations other than

established stations are not shown here (see Rowe et al- Open file report in preparation

for latitude and longitude of sample collection sites). Inset map of Washington with black

box depicting Mt. St. Helens and vicinity.

187

O

$

$

O

$ $

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

-/

.

7ASHINGTON

-434(%,%.3!3(34!4)/.3

)LJXUH

.,/20(7(56

188

$

&

%

'

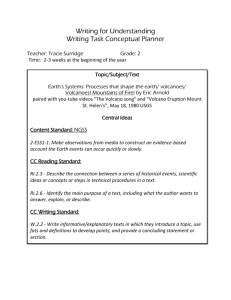

)LJXUH$VKFROOHFWLRQRQ$FOHDQIODWVXUIDFHV%DWDVKFROOHFWLRQVWDWLRQV

&RQVQRZFRYHUHGVXUIDFHVDQG'LQSHWURORJ\VSLGHUV,QVHWLQ%VKRZVWKH

LQQHUEXFNHWOHIWZLWKUHGWDSHPDUNLQJWKHGUDLQDJHVOLWVDQGORZHUEXFNHW

ULJKWZLWKGUDLQDJHKROHVLQEDVH%ROWVLQORZHUEXFNHWSURYLGHVXSSRUWDQG

VXVSHQVLRQRIXSSHUEXFNHW,QVHWLQ'SURYLGHVDWRSYLHZRIWKHSHWURORJ\

VSLGHUZLWKQ\ORQQHWWLQJIRULGHQWLILFDWLRQDQGFROOHFWLRQRIKRWEDOOLVWLFVRQWKH

OHIWDQGEDIIOHGFRPSDUWPHQWVIRUDVKDQGOLWKLFVRQWKHULJKW

189

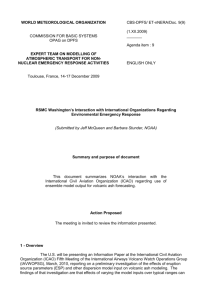

flat surfaces (Fig. 34a). Collection stations were located with line of sight to the volcano

ranging from 2.4 to 10 km from the vent (Fig. 33). Each station is comprised of a rebar

suspended double-bucket. The inner bucket, with drainage slits approximately a third of

the way up from the bottom, is suspended within the outer bucket to allow excess water

to drain without significant loss of ash (Fig. 34b). Collection intervals varied from less

than 3 days to greater than 15 days at individual stations until December 2, 2004 (Fig.

35). Ash collection at the established stations was a function of accessibility of the

station, and predominant wind directions for the period preceding collection (Fig. 35).

Following December 2, 2004, most ash collection has been of discrete ash producing

events (either dome collapses or phreatic explosions) on snow-covered or otherwise clean

surfaces. Snow-covered surfaces provide easy identification of new ash, and allow for

tracking of deposited ash to its source (Fig. 34c). Additional ash samples collected in

August 2005 were made from petrology spyders located within the crater (Fig. 34d).

Fifteen samples collected between October 1, 2004 and March 9, 2005 were

utilized in this study (Table 13). Of the 15 samples studied here, 12 are ash samples

spanning October 1, 2004 to March 9, 2005, two are dome fault-gouge (collected

November 4, 2004 and February 22, 2005) and one sample is of a crater debris flow

(October 20, 2004) associated with collapse of the initial spine (Table 13). See Thornber

et al. (in preparation) and Pallister et al. (in preparation) for description of dome fault

gouge and crater debris flow collection.

Of the five early explosive events, only the three events (October 1, 4 and 5)

included in this study resulted in downwind ash fallout between October 1 and October 5,

$6+&2//(&7,2167$7,21

3'

3'7

3 7 ' 7 190

-/

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

$

&2//(&7,21

,17(59$/6

'$<6

'$<6

'$<6

'$<6

'$<6

!'$<6

6$03/(&2//(&7,21'$7(PPGG\\

)LJXUH&ROOHFWLRQLQWHUYDOVIRUDVKFROOHFWLRQVWDWLRQVVHH)LJXUHIURP

2FWREHUWR'HFHPEHU

191

Table 13. Ash, gouge, and crater debris samples included in this study

Sample

MSH04E1DZ_1

MSH04E2A03_A1

MSH04E3RANDLE_2

MSH04A20_10_11

MSH04A20_10_16

MSH04A09_10_12

MSH04A21_10_20

MSH04A04_11_2

MSH04MR_11_4

MSH05JP_1_14A

MSH05JV_1_19

MSH05DRS_3_9_4

SH303-1

SH307-1

SH300-1

1

Type

ash

ash

ash

ash

ash

ash

ash

ash

ash

ash

ash

ash

Gouge

Gouge

Crater

Debris2

Date collected

10/1/2004

10/4/2004

10/5/2004

10/11/2004

10/16/2004

10/12/2004

10/20/2004

11/2/2004

11/4/2004

1/14/2005

1/19/2005

3/9/2005

11/4/2004

2/22/2005

10/20/2004

Eruption date1

10/1/2004

10/4/2004

10/5/2004

10/5/04-10/11/04

10/11/04-10/16/04

10/4/04-10/12/04

10/15/04-10/20/04

10/16/04-11/2/04

11/4/2004

1/13/2005

1/16/2005

3/8/2005

11/4/2004

2/7/2005

10/20/2004

Eruption dates for crater debris and gouge samples estimate by John Pallister. 2Only fine

material collected from the crater debris flow is included in this study. Further details of

ash samples are available in Rowe and others (Open File Report, in preparation).

192

2004 (Major et al., 2005). Samples among the complete suite of Mount St. Helens 20042005 ashes (Rowe et al., Open File Report in preparation) were selected for this study

based on most detailed sampling intervals, wind directions, and volume of material.

Analytical methods

Major element compositions of groundmass glass (and melt inclusions where

possible), feldspars, and mafic phenocryst phases (amphibole, clinopyroxene, and

hypersthene) were measured for all 12 ash samples by electron microprobe analysis

(EMPA). In order to reduce sampling biases, 25-50 feldspars, ~20 mafic phenocrysts,

and 10-20 glasses were analyzed from each sample, proportional to their relative

abundances in ash samples. Backscatter electron (BSE) images were taken of all the ash

and dome gouge samples in order to document heterogeneity of ash particles within and

between samples. Trace element concentrations of the feldspars from 14 of the samples

were obtained by laser ablation inductively-coupled plasma mass spectrometry (LA-ICPMS). Feldspar analyses (major and trace) only were made from the 2 dome fault-gouge

samples and only feldspar trace element concentrations were measured for the crater

debris sample (SH300-1; Table 13).

Analyzed samples were not sieved and phenocrysts and glasses of all sizes were

analyzed to reduce the possible biases created by mechanical sorting during transport

(Houghton et al., 2000). Phenocrysts for LA-ICP-MS and EMPA were targeted

indiscriminately, as groundmass or phenocryst edges were often not preserved in ash

grains. EMPA measurements were made on a Cameca SX-100 at Oregon State

University. Glass EMPA measurements were conducted using a modified procedure to

193

that suggested by Morgan and London (1996). Na and K were counted for 60 seconds

using a 2 nA beam current, 15 keV accelerating voltage and a 10 Pm beam diameter. Si,

Al, Ti, Ca, Mn, Mg, Fe, P, S, and Cl, were analyzed using a 30 nA beam current, 15 keV

accelerating voltage and 10 Pm beam diameter. Count times ranged from 10-50 seconds

depending on the element of interest. The small beam size (~20 Pm is optimal) is

required in this case due to the small size of glassy fragments present in the ash (Morgan

and London, 1996). Feldspars (30 nA) and mafic phases (50 nA) were measured using a

15 keV accelerating voltage and 5 Pm and 1 Pm beam diameters, respectively. When

possible, analyses of phenocryst phases were made within 15 Pm of the grain boundary.

A rhyolite glass standard (USNM 72854 VG-568), a feldspar standard (Labradorite

USNM 115900), and a pyroxene standard (Kakanui augite USNM 122142) were

analyzed prior to each analytical session. Glass standard statistics are presented in Rowe

et al. (USGS OFR- in prep).

Trace element concentrations of feldspars (Li, Ti, Sr, Ba, La, Ce, Pr, Nd, Eu and

Pb) were measured by LA-ICP-MS in the W.M. Keck Collaboratory for Plasma

Spectrometry, Oregon State University. Analyses were performed using a stationary laser

(70 Pm spot size) to ablate a progressively deepening crater in the sample materials,

requiring targeted feldspars to have a diameter greater than ~80 Pm. Due to the large spot

size required and fine grain size of the feldspars in the ash, laser ablation analyses were

made close to the center of inclusion free grains. Each individual analysis represents 40

seconds of data acquisition during ablation with background count rates measured for 30

seconds prior to ablation. A pulse frequency of 4 Hz resulted in an ablation crater ~15 Pm

194

deep. Trace element abundances were calculated relative to the NIST 612 glass standard,

which was analyzed under identical conditions throughout the analytical session. USGS

glass BCR-2G was also analyzed as a secondary standard. Counts were normalized to

29

Si and concentrations determined following the method of Kent et al. (in preparation).

Precision of trace element analysis is presented in Kent et al. (in preparation), however Li

concentrations, most relevant to this study, have a precision of 8% (1 standard deviation).

RESULTS

Glass

Ash sample fragments were dominated by crystalline to microcrystalline textures

with groundmass crystallization resulting in the formation of crystalline silica and

feldspar microlites (Fig. 36). Matrix textures of the juvenile dome are described by

Pallister et al. (in preparation). Al2O3 and SiO2 concentrations in the initial 179 glass

analyses are used to discriminate between analyses that have been significantly modified

as a result of the groundmass crystallization of feldspar and quartz microlites (Fig. 36).

The resulting 81 reliable glass analyses are hereafter referred to as “clean glass.” Most

clean glass analyses are of glass adhered to phenocrysts or from pumice fragments.

Major element concentrations of clean glass are highly variable, due to localized effects

of melt crystallization and lithic heterogeneity of the ash. Clean glass analyses range

from 52-79 wt% SiO2 but are dominantly between 72-78 wt% SiO2 (Table 14). In

addition to a wide compositional range there is no apparent temporal trend to suggest a

195

IHOGVSDU

$O2:(,*+73(5&(17

6L2:(,*+73(5&(17

)LJXUH$O2YHUVXV6L2ZWIRUJURXQGPDVVJODVVDQDO\VLVRIDVKIUDJ

PHQWV%LIXUFDWLQJWUHQGWRZDUGIHOGVSDUDQGTXDUW]HQGPHPEHUVLVFKDUDFWHULVWLF

RIWKHKLJKO\FU\VWDOOLQHJURXQGPDVV,QVHW[UD\PDS$O.AVKRZVFU\VWDOOL]D

WLRQRIIHOGVSDURUDQJHDQGTXDUW]EOXHLQWKHMXYHQLOHJURXQGPDVV

196

systematic change in the melt composition over the course of the 2004-2005 sampling

(Fig. 37).

Mafic phases

Mafic phenocrysts analyzed from the 12 ash samples included hypersthene,

amphibole, and clinopyroxene.

Mafic phases were distinguished from feldspar and

groundmass during backscatter imaging on the electron microprobe. Hypersthene is the

dominant mafic phenocryst in the ash and displays a wider range in Mg# (50.8-75.2) than

observed in new dome samples (Mg# 54-71). While discrete clinopyroxene phenocrysts

are present in the early ash samples, they are rare in the new dome material, often

associated with xenolith fragments. Clinopyroxene was not observed in ash deposits

generated after Oct. 20, 2004. Amphibole compositions are also highly variable, with a

mean Mg# of 59.8 ± 13 (1 standard deviation) and Al2O3 from 6 to ~16wt%, comparable

to the range observed in both new dome dacite (mean Mg# of 64.7± 4.9; 6 to 14wt%

Al2O3) and in 1980-1986 dome rock (Thornber et al., in preparation). In addition,

thicknesses of the outermost reaction rims of amphiboles are variable, with thick reaction

rims present on some grains. Rim thickness on amphiboles becomes less variable with

time and begins to resemble the new dome (only rare thick rims by March 8, 2005

tephra). The presence of thick-rimmed amphibole grains and clinopyroxene is

characteristic of 1980-1986 magmas and distinct from the uniformly thin (~5 Pm)

decompression rim around 2004-2005 dacitic amphiboles, thus suggesting that older

Mount St. Helens material is mixed with the juvenile ash (Rutherford and Hill, 1993;

Rutherford and Devine, in preparation). Due to the high compositional variability in the

197

.2:(,*+73(5&(17

2FWYHQWH[SORVLRQ

2FWYHQWH[SORVLRQ

2FWYHQWH[SORVLRQ

$

%

6L2:(,*+73(5&(17

1RYGRPHFROODSVH

-DQGRPHFROODSVH

-DQYHQWH[SORVLRQ

0DUYHQWH[SORVLRQ

0J2:(,*+73(5&(17

(

6L2:(,*+73(5&(17

&

'

6L2:(,*+73(5&(17

.2:(,*+73(5&(17

0J2:(,*+73(5&(17

6L2:(,*+73(5&(17

2FW 2FW

2FW 2FW1RY

2FW

3UHJODVVDQGLQFOXVLRQV

6+JODVVDQGLQFOXVLRQV

.2:(,*+73(5&(17

0J2:(,*+73(5&(17

6L2:(,*+73(5&(17

)

6L2:(,*+73(5&(17

)LJXUH6L2YHUVXV$&0J2DQG').2ZWIRUFOHDQJODVVDQDO\VHV

VHHWH[WIRUIXUWKHUH[SODQDWLRQ%OXHILHOGLVGHILQHGE\ROGHUWHSKUDDQGGRPH

JODVVFRPSRVLWLRQV0HOVRQ6DUQD:RMFLFNLHWDOE<HOORZILHOG

GHILQHVWKHUDQJHRIJODVVDQGPHOWLQFOXVLRQFRPSRVLWLRQVIRU6+DQG6+

GRPHVDPSOHV3DOOLVWHUHWDOLQSUHSDUDWLRQ3ORWVDUHGLYLGHGLQWRHDUO\YHQW

HUXSWLRQV$DQG'DVKFROOHFWLRQVWDWLRQVIURP2FWREHUWR1RYHPEHU

%DQG(DQGSRVW1RYHPEHUGRPHFROODSVHDQGYHQWH[SORVLRQV

&DQG)(UXSWLRQGDWHVFRUUHVSRQGWRVDPSOHQXPEHUVLQ7DEOH

1.40

4.37

2.75

0.09

0.01

0.14

CaO

Na2O

K2O

P2O5

SO2

Cl

100.44

0.04

0.00

0.07

2.83

4.28

2.09

0.06

0.00

0.89

15.91

0.27

74.00

97.86

0.12

0.01

0.08

2.28

4.77

1.66

0.09

0.04

1.21

15.02

0.26

72.32

100.53

0.09

0.00

0.04

4.52

2.92

0.52

0.16

0.02

1.42

13.79

0.24

76.81

99.61

0.02

0.00

0.03

4.21

3.15

0.57

0.05

0.00

0.97

12.64

0.34

77.63

98.59

0.01

0.01

0.07

3.41

3.97

1.24

0.02

0.00

0.53

14.24

0.34

74.75

101.45

0.00

0.00

0.06

3.28

4.26

2.70

0.06

0.00

0.97

18.38

0.22

71.52

99.98

0.05

0.01

0.05

4.12

4.47

1.00

0.10

0.00

0.47

14.00

0.22

75.49

JP1-14

99.46

0.05

0.01

0.18

3.19

5.49

0.33

0.00

0.00

1.32

12.60

0.23

76.06

JP1-14

100.73

0.01

0.01

0.03

4.49

4.45

1.70

0.04

0.02

0.63

15.34

0.18

73.83

JP1-14

100.22

0.03

0.01

0.23

5.33

2.77

1.22

0.09

0.00

0.53

13.78

0.22

76.01

JP1-14

99.59

0.03

0.00

0.52

5.15

1.91

2.27

1.19

0.10

5.64

13.97

1.69

67.12

JP1-14

99.90

0.03

0.00

0.04

5.01

1.62

1.29

0.03

0.01

0.64

12.69

0.16

78.38

JP1-14

102.19

0.02

0.00

0.09

3.03

5.54

1.50

0.07

0.05

1.44

16.05

0.26

74.14

JV1-19

3

(MSH04, MSH05) have been removed- see Table 13 for complete sample names. Total Fe as FeO.

96.38

0.03

0.02

0.05

2.28

4.55

1.68

0.03

0.01

0.42

16.05

0.09

71.17

JV1-19

Notes: 1Juvenile glass as described in text is based on MgO and K2O fields defined by SH304 and SH305 glass and inclusion analyses. 2Sample prefixes

98.71

0.22

MgO

Total

1.19

0.05

14.72

Al2O3

MnO

0.47

FeO3

73.30

SiO2

TiO2

Sample2 E2AO3-1A E2AO3-1A A20-10-11 A20-10-16 A20-10-16 A21-10-20 A04-11-2

Major element oxides

Table 14: Electron microprobe analyses of clean, juvenile glass 1.

198

199

ash and in the case of hypersthene and clinopyroxene, lack of comparison with older

Mount St. Helens tephras and lavas, the mafic phases will not be discussed further at this

time. See Thornber et al. (in preparation) for more discussion of textural and

compositional variability of Mount St. Helens 2004-2005 amphiboles.

Feldspars

Feldspar phenocrysts in ash, gouge, and crater debris display a wide

compositional variation. Feldspar crystals in the ash range from An87-28, overlapping

both the new dome (An53-33) and dome samples from 1980-1985 (An51-34). Rim

compositions of the new dome have a more restricted range of An46-34, again similar to

that observed in the 1980’s dome rocks (Rowe et al., 2005; Streck et al., in preparation).

A total of 266 LA-ICP-MS analyses were completed on 14 of the samples included in

this study. Ba and Sr concentrations are the most variable, ranging from 14.5-224.6 Pg/g

and 532-1603ҏ Pg/g respectively. La (1.0-9.7ҏPg/g), Pb (0.3-7.0 ҏPg/g) and Li (6.9-48.5

ҏPg/g) also are highly variable (Rowe et al., Open File Report- in preparation). La has a

well defined, and Pb a weakly defined positive correlation with Ba, while Sr is negatively

correlated with Ba (Fig. 38). Li concentrations do not correlate with other major or trace

elements. While variability in most of the trace elements is within the range predicted by

changes in feldspar/melt partition coefficients with An content, higher Li concentrations

in a small percentage of the feldspars would require ~200ҏ Pg/g Li in the melt,

significantly greater than observed Li in the bulk dacite (21-28ҏ Pg/g; Fig. 38; Bindeman

et al., 1998, Thornber and Pallister, same issue; Kent et al., manuscript in prep). In ash

samples collected after November 4, 2004 a significant change occurs in the Li anomaly,

200

Figure 38. Selected trace element concentrations of feldspars analyzed from ash samples.

Abbreviated sample names are listed (see Table 13 for complete identifications).

/LMJJ

3EMJJ

%

$

%DMJJ

)LJXUH

'

&

$

$

05

-3$

%DMJJ

('=

($$

(5$1'/(

$

-9

$

'56

6+

6UMJJ

/DMJJ

201

202

Figure 39. Histograms of Li concentrations in feldspars for each of the 14 samples

examined. Li concentrations greater than 30 Pg/g (dashed line) in ash samples prior to

November 4, 2004 (MR_11_4) coincide with the juvenile feldspars of dome sample

SH304. Eruption dates of samples are in parentheses. Abbreviated sample names

correspond to Table 13.

203

('=B ($B$

(5$1'/(B $BB

-3BB$

$BB

-9BB

6+

$BB

$BB

6+

6+

05BB

'56BBB

/LMJJ

/LMJJ

)LJXUH

204

with Li concentrations more homogenous and consistently lower compared to earlier ash

samples, with a maximum concentration of 30ҏ Pg/g (Fig. 39). This reduction in Li

abundance is also observed in dome samples following the collection of Mount St.

Helens dome sample SH304 (Kent et al., in preparation; Kent et al., manuscript in prep).

DISCUSSION

October 1-5, 2004 ash explosions

Identification of a juvenile component

Identification and quantification of juvenile material in early eruptive events can

be critical to evaluating the potential for continuation or waning of an eruption. Juvenile

material in the early ash component is evident from specific glass compositions and high

feldspar Li content. Most glass major element compositions overlap with 1980-1982

(Melson, 1983; Sarna-Wojcicki et al., 1982b) and pre-1980 eruptions (Sarna-Wojcicki et

al., 1982b). However, matrix glass and melt inclusion analyses of 2004-2005 Mount St.

Helens samples SH304 and SH305 are distinctly lower in MgO (<0.5 wt%) and higher in

K2O (up to 5.5 wt% K2O) at comparable SiO2 concentrations (Fig. 37; Table 14; Pallister

et al., in preparation). Based upon the combined variations of MgO and K2O, glass

analyses can be categorized into what appear to be older glassy ash fragments and

juvenile material. None of the clean glass analyses from the October 1 and October 5,

2004 eruptions are juvenile while ~20% of the October 4 glasses have juvenile

characteristics. The estimated percentage of juvenile material drops significantly, to less

than 9% for October 4 and 5% overall for the early explosive events however because of

205

high proportion of highly crystallized groundmass present (Fig. 36). In addition, all of

the analyzed pumice fragments fall within the compositional fields defining the older

volcanics. Backscatter electron images in Figure 40b and 40d provide a textural

comparison between juvenile crystalline groundmass (40b) and a pumiceous glass

fragment compositionally similar to the older volcanics (40d). Both textural and

compositional comparisons between the various groundmass types are critical to avoiding

a common misconception that clean glass particles (for example Figure 40d) are always

representative of the juvenile component associated with the eruption (for example,

Watanabe et al., 1999; Swanson et al., 1995; Sarna-Wojcicki et al., 1982a).

Previous studies of 1980’s tephra and dome samples indicate that feldspars from

1980’s lavas and tephras have a maximum Li concentration of ~30ҏ Pg/g (Berlo et al.,

2004, Kent et al., 2005). However, feldspars of early 2004 dome sample SH304 (erupted

~October 18, 2004) have concentrations ranging from 30-40 ҏPg/g Li, distinctly higher

than that of older Mount St. Helens feldspars (Berlo et al., 2004; Kent et al., 2005), thus

allowing us to distinguish between juvenile and older feldspars present in the October 1,

2004 to October 5, 2004 ash (Fig. 39). Based on this evidence, 10% of the feldspars from

the October 1 eruption are juvenile while 28% of the October 4 feldspars are juvenile.

Despite only two feldspars from the October 5 ash providing reliable Li concentrations,

do to the small grain size of the sample, one of the two has a high Li concentration. Both

the glass and feldspar compositions suggest an increase in the proportion of juvenile

material from October 1 to October 4, 2004, however the feldspar compositions suggest

the presence of a significant juvenile component as early as October 1, whereas the glass

206

$

&

MP

MP

%

MP

'

MP

)LJXUH%DFNVFDWWHUHOHFWURQ%6(LPDJHVRI$6+JURXQGPDVV%

06+05BBDVKIUDJPHQWIHOGVSDU/LFRQFHQWUDWLRQRIҏMJJ&

JODVV\IUDJPHQWRIDVKZLWKH[WHQVLYHSODJLRFODVHPLFUROLWHFU\VWDOOL]DWLRQIURP

VDPSOH06+($B$DQG'¶VSXPLFHIUDJPHQWIURPVDPSOH

06+($B$

207

analyses do not indicate the presence of juvenile material until October 4. The nearly 3x

increase in juvenile material from October 1, 2004 to October 4, 2004 is suggestive of

upward movement of magma within the shallow conduit, consistent with the appearance

of hot dacite on the surface of the crater floor on October 11, 2004.

Considering issues of matrix interference, higher estimates of the percentage of

juvenile material based upon feldspar trace element analyses compared with estimates

using the glass compositions is a result of quartz and feldspar microlite crystallization

evident from early dome samples (Fig. 36, 40). This same microcrystalline texture is

observed in all of the ash samples suggesting that shallow magmatic crystallization has

affected textures of juvenile ash particles, similar to observations by Cashman and

Blundy (2004) with regard to early 1980 eruptions.

Evidence for a volatile eruption trigger

The high Li concentrations observed in early erupted feldspars from the ash (max

of 48.5ҏ Pg/g Li) and dome samples (max of 41.5ҏ Pg/g Li) may have implications for the

initiation of the recent eruption. As previously discussed, the high Li content observed in

feldspars would require a melt concentration of roughly 200 ҏPg/g Li based on

mineral/melt partition coefficients, despite the lower 21-28ҏ Pg/g Li observed in the bulk

dacite. As suggested by Berlo et al. (2004), the discrepancy between the high Li

feldspars and low Li groundmass could be explained by vapor enrichment of shallowstored magma, followed by the loss of Li in the groundmass as a result of degassing.

Kent et al. (manuscript in prep) predict that vapor enrichment must have occurred less

than ~1 year (and potentially within just a few days) before eruption since enrichment

208

prior to that time would have resulted in diffusional equilibration of feldspars in gabbroic

inclusions- which have lower Li than groundmass plagioclase. A CO2 output of 2415

tons/day, measured on Oct. 7, 2004, followed by a steady decline in ensuing months also

may indicate a greater volume of gas early in the eruption, although the higher gas output

could also result from higher extrusion rates early in the eruption (McGee et al., in

preparation). The high Li concentrations in feldspars in conjunction with higher CO2

output measured on October 7 may indicate the presence of a significant volume of

excess gas prior to the onset of the eruption. Hence, Li-enriched plagioclase in the

earliest eruption products indicates that high vapor pressure could have triggered the

recent eruption.

Ash generation

Airborne ash is produced by both vent explosions and dome collapse events at

Mount St. Helens. Two general mechanisms are typically described for the generation of

ash during vent explosions. In magmatic explosions, exsolution and expansion of gases in

magma during ascent leads to frothing of the magma, vesiculation and fragmentation

(Heiken, 1972, Cashman et al., 2000). In contrast, phreatomagmatic eruptions primarily

result from the rapid expansion of, in the case of Mount St. Helens, meteoric water as it

interacts with magma and/or hot rock at depth (Mastin et al., in preparation; Morrissey et

al., 2000). Mount St. Helens 2004-2005 vent explosions result in a greater area of

dispersal than dome collapse events with fallout reported as far as Ellensburg, WA

following the March 8, 2005 vent explosion (Mastin et al. 2005; Scott et al., in

preparation). In principle, particle shape is controlled by the shape and density of the

209

vesicles in magmatic eruptions while glassy fragments in phreatomagmatic eruptions are

often pyramidal or blocky (Heiken, 1972). In both cases however, relatively rapid

cooling should result in the generation of glassy material when magma is present.

Intracrater pyroclastic block and ash flows of this eruption are associated with

dome collapse events that result from dome growth and oversteepening (Vallance et al.,

in preparation). Dome collapse events with elutriation of fine ash particles, while

occurring much more frequently than vent explosions, are typically less significant,

sending ash up to 30, 000 ft into the air and falling proximal to the edifice (Scott, in

preparation). In addition to vent explosions and dome collapse events small volumes of

airborne ash may be distributed by elutriation during steaming of the dome, a relatively

low energy, and passive mechanism for ash transportation.

Mechanisms of ash generation and distribution of the recent Mount St. Helens

eruption are not discernable using traditional tools of grain shape, volume of glass, or

textural and compositional heterogeneity of ash particles (see above descriptions). This

eruption provides a case in which very little glassy material is present in the ash, and only

a small percentage of that is considered to be juvenile. Juvenile groundmass observed in

the dome and in the ash is crystalline (quartz and feldspar) with localized vesiculation

and devitrification (Fig. 40a,b). Water by difference measurements of melt inclusions

indicate that the juvenile magma is extensively degassed prior to eruption, and as

supported by gas emission data for this eruption, suggests that expansion of magmatic

gas, either during vent explosions or dome collapses, is not responsible for ash generation

(Pallister et al., in preparation; McGee et al., in preparation). In addition, the high

210

proportion of lithics and small proportion of clean juvenile glass shards and/or pumice

fragments suggests these explosions are dominantly phreatic in origin and that

crystallization of the rising magma had occurred prior to the explosive events.

By comparing geochemical analyses of multiple phases in conjunction with the

BSE imaging of ashes derived from dome collapse events and vent explosions, we have

attempted to distinguish between those processes. Major element concentrations of

matrix glass and inclusions from the January 13, 2005 dome collapse correlate well with

juvenile compositions established by glass analyses in dome samples SH304-305 (Fig.

37). In contrast, only 40% of the glass analyses from the January 16, 2005 vent

explosion correlate with the juvenile fields. This discrepancy demonstrates that the vent

eruptions contain a higher percentage of exotic fragments derived from crater debris in

the vent area. However, a distinct contrast is observed when comparing glass

compositions from the January 13, 2005 and November 4, 2004 dome collapse events.

Whereas the glass from the January 13, 2005 event is dominated by juvenile glass, the

November 4, 2004 ash is dominated by older glass (Fig. 37). This observation suggests

that the part of the early dome (or uplift area) responsible for ash generation contained a

significant proportion of older material but by January 2005 was dominantly composed of

juvenile dacitic material. This conclusion is also supported by field observations and preNovember 2004 dome samples (Pallister et al., in preparation; Reagan et al., in

preparation).

Juvenile ash fragments from dome collapse events (November 4, 2004 and

January 13, 2005) and vent explosions (January 16, 2005 and March 8, 2005) have nearly

211

identical groundmass textures, as described above (Fig. 41). Grain shape between

samples is also strikingly similar. Ash particles dominated by large phenocrysts often

reflect the general shape of that phenocryst and are more angular while particles

dominated by groundmass typically vary from round to subangular. Due to the

similarities in grain shape and texture for the juvenile matrix, commonly cited methods

for ash generation related to different types of events do not explain the observations (i.e.

Heiken, 1972; Cashman et al., 2000; Morrissey et al; 2000). The likely predominant

source of ash therefore is the dome fault gouge, which, comprising the outer 1-3m of the

dome, becomes increasingly disaggregated towards the exterior of the dome. Gouge

particles are dominantly rounded to subangular, similar to the ash (Fig. 41e,f). Particle

size distribution of dome gouge and ash samples generated from both dome collapse and

vent explosions also suggests that they are of similar origin (Thornber et al., in

preparation). Groundmass textures of dome gouge extruded on November 4, 2004

(SH303-1) are very heterogeneous, suggesting that at this time the gouge was comprised

of a high percentage of exotic wallrock lithics. This heterogeneity also explains the

dominance of older glass compositions in the November 4 dome collapse ash. In

addition, feldspar Li concentrations in the November 4 ash match those of the gouge and

do not correlate well with either the SH304 or SH305 dome samples (Fig. 39; Kent et al.,

in preparation). Dome fault gouge collected on February 22, 2005 (SH307-1) is much

more homogenous, with groundmass textures resembling the growing dome, and

groundmass textures and grain shapes identical to the ash. This homogeneity is reflected

in the January 13, 2005 dome collapse ash in which glass compositions match that of the

212

$

'

MP

MP

%

(

MP

MP

&

MP

)

MP

)LJXUH%6(LPDJHVRIFKDUDFWHULVWLFDVKSDUWLFOHVIURPGRPHFROODSVHHYHQWV

$%YHQWH[SORVLRQV&'DQGGRPHJRXJH()$5RXQGHGDVKIUDJPHQW

IURPVDPSOH06+-3BB$VDPSOLQJGRPHFROODSVHHYHQWRQ-DQXDU\

%0RUHGLVDJJUHJDWHGDVKSDUWLFOHIURPWKHVDPHVDPSOHDV$&

6XEURXQGHGDVKIUDJPHQWZLWKJUDLQVKDSHFRQWUROOHGE\ODUJHUIHOGVSDUDQG

K\SHUVWKHQHSKHQRFU\VWVIURPVDPSOH06+-9BBVDPSOLQJWKH-DQXDU\

YHQWH[SORVLRQ'/DUJHO\GHYLWULILHGDVKSDUWLFOHVHH[UD\PDSLQILJXUH

IURP0DUFKYHQWH[SORVLRQ(/RZPDJQLILFDWLRQ%6(LPDJHRI

GLVDJJUHJDWHGGRPHJRXJHVDPSOH6+)(QODUJHPHQWRIURXQGHGFODVW

IURP(VKRZLQJFKDUDFWHULVWLFDVKPRUSKRORJ\

213

growing dome (Fig. 37). Textural and geochemical evidence presented here confirms

that airborne ash is generated from the dome fault gouge, likely entrained with large

pieces of crater debris or dome dacitic blocks during vent explosions and dome collapse

events.

Ash collected more distally as a result of passive steaming is dissimilar to that of

the dome collapse and vent explosions. Texturally, the ash collected between October 6

and November 2, 2004 at established collection stations has a high proportion of lithic

fragments. Pumice fragments, compositionally identical to 1980’s pumice, are the

dominant groundmass type rather than the juvenile crystalline groundmass commonly

found during discrete ash producing events. Only a small proportion of clean juvenile

glass is present in all of the ash samples collected during this interval and there is no

systematic variation in proportion of juvenile glass with time, despite the appearance of

hot dacite on October 11, 2004. Similar results are observed for Li concentrations in

feldspars during this time interval, with high Li concentrations in only ~5% of the

analyzed feldspars despite identifying ~21% juvenile feldspars in the fine material

collected from the October 20, 2004 crater debris flow sample (SH300-1). The low

proportion of juvenile glass, groundmass textures, and feldspars in the distal ash suggests

these samples have experienced a greater degree of contamination. The low energy

transport of ash by steaming of the dome appears to only entrain the lowest density ash

particles, resulting in a higher proportion of pumice fragments in these ash samples.

Also, as a result of the small volume of material that can be transported, the affects of

contamination from other sources, such as windblown particulates, is more significant.

214

CONCLUSIONS

This textural and geochemical examination of 2004-2005 Mount St. Helens ash

has provided several important observations and conclusions with regard to the nature of

early eruptive events and processes of ash generation and transportation.

1. High Li concentrations in feldspars suggest that the earliest phases of the recent

eruption may have contained a more significant volatile/vapor phase than originally

thought and may therefore provide evidence for a possible eruption trigger resulting,

in part, from the presence of an excess volatile phase.

2. Lithium concentrations in feldspars indicate a potential increase in the proportion

juvenile material from October 1 to October 5, 2004, tracking the rise of magma prior

to the emergence of hot dacite on October 11, 2004. High Li concentrations in

feldspar is only useful as a tracer for juvenile material during the beginning stages of

the eruption since after ~November 20, 2004 (estimated eruption date of SH305) Li

concentrations drop to levels comparable to 1980-86, suggesting that the volatile

enriched magma was only a shallow cap on the larger magma body.

3. Clean glass in ash samples is dominated by older volcanic material while juvenile

groundmass is typically crystalline (quartz and feldspar) with localized devitrification

and patchy, very fine vesiculation. This conclusion is significant in that it is typically

the clean glass that is characterized as juvenile during an eruption.

215

4. Groundmass textures, grain shapes, and compositional similarities between ash from

vent explosions and dome collapse events and dome fault gouge particles indicate that

the gouge is a predominant source of ash. Heterogeneity observed in early ash

samples correlates with observations that the early extruded dome material and fault

gouge contained a significant proportion of older volcanic material. Increasing

homogeneity of ash with time is consistent with a similar trend in dome and fault

gouge samples.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all of the CVO staff and volunteers who assisted

in the establishment of ash stations and collection of Mount St. Helens ash. We would

especially like to thank A. Eckberg, S. McConnell, and T. Herriot who assisted with

drying, sorting, and weighing of ash samples, Dan Gooding and Dave Ramsey for

assistance in the field and with the collection site map, and F. Tepley (OSU microprobe

lab) for providing microprobe time. The Mount St. Helens petrology working group

provided valuable discussion and feedback for this study. This work was supported in

part by the National Science Foundation grant EAR 0440382.

REFERENCES

Bindeman, I.N., Davis, A.M., and Drake, M.J. (1998). Ion microprobe study of

plagioclase-basalt partition experiments at natural concentration levels of trace elements.

Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 62, 1175-1193.

216

Berlo, K., Blundy, J., Turner, S., Cashman, K., Hawkesworth, C., and Black, S. (2004).

Geochemical precursors to volcanic activity at Mount St. Helens, USA. Science, 306,

1167-1169.

Cashman, K., Sturtevant, B., Papale, P., and Navon, O. (2000). Magmatic fragmentation.

In: H. Sigurdsson (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Volcanoes. Academic Press, London. 421-430.

Cashman , K., and Hoblitt, R. (2004). Magmatic percursors to the 18 May 1980 eruption

of Mount St. Helens, USA. Geology, 32, 2, 141-144.

Friedman, J.D., Olhoeft, G.R., Johnson, G.R., and Frank, D. (1982). Heat content and

thermal energy of the June dacite dome in relation to total energy yield, May-October

1980. In Lipman, P. and Mullineaux, D. (Eds.), The 1980 eruptions of Mount St. Helens,

Washington. US Geological Survey Professional Paper, 1250, 557-567.

Heiken, G. (1972). Morphology and Petrography of volcanic ashes. GSA Bulletin, 83,

1961-1988.

Houghton, B. Wilson, C., Smith, R., and Gilbert, J. (2000). Phreatoplinian eruptions. In

H. Sigurdsson (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Volcanoes. Academic Press, London. 513-526.

Kent, A.J.R., Rowe, M.C., Thornber, C., and Pallister, J. (2006). Laser ablation ICP-MS

measurements of trace-element and Pb isotopic compositions of Mt St Helens dome

material from 2004-2005: Implications for magmatic origin and evolution Li

concentrations. US Geological Survey Professional Paper, in preparation.

Major, J., Scott, W., Driedger, C., and Dzurisin, D. (2005). Mount St. Helens erupts

again: activity from September 2004 through March 2005. US Geological Survey Fact

Sheet 2005-3036.

Mastin, L.G., Vallance, J.W., Thornber, C.T., Schneider, D., Sherrod D., and Ewert, J.W.

(2006). Evidence bearing on heights of phreatic plumes, with field data from mar-8 MSH

explosion. US Geological Survey Professional Paper, in preparation.

Mastin, L.G., Sherrod, D., Vallance, J.W., Thornber, C.T., and Ewert, J.W. (2005). The

roles of magmatic and external water in the March 8 tephra eruption at Mount St. Helens

as assessed by a 1-D steady plume-height model. EOS 86(52), Fall Meet. Suppl. Abstract

V53D-1597.

McGee, K., Gerlach, T., and Doukas, M. (2006). Degassing of CO2, SO2, and H2S from

MSH during the 2004-05 eruption. US Geological Survey Professional Paper, in

preparation.

217

Melson, W. (1983). Monitoring the 1980-1982 Eruptions of Mount St. Helens:

Compositions and Abundance of Glass. Science, 221, 4618, 1387-1391.

Morgon, G. IV., and London, D. (1996). Optimizing the electron microprobe analysis of

hydrous alkali aluminosilicate glasses. American Mineralogist, 81, 1176-1185.

Morrissey, M., Zimanowski, B., Wohletz, K., and Buettner, R. (2000). Phreatomagmatic

fragmentation. In H. Sigurdsson (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Volcanoes. Academic Press,

London. 431-445.

Pallister, J., Hoblitt, R., and Reyes, A. (1992). A basalt trigger for the 1991 eruptions of

Pinatubo volcano? Nature, 356, 426-428.

Pallister, J. (2006). Petrology and field geology of the 2004-2005 Mount St. Helens lava

dome – implications for magmatic plumbing, US Geological Survey Professional Paper,

in preparation.

Rowe, M.C., Thornber, C., and Kent, A.J.R. (2005). Petrology and geochemistry of

Mount St. Helens ash before and during continuous dome extrusion. Geochimica et

Cosmochimica Acta, 69, 10, supplement 1, A272.

Rutherford, M.J., and Devine, J.D. (.2006). Experimental constraints on pre-eruption

magma conditions of the 2004-2005 Mount St. Helens dacite. US Geological Survey

Professional Paper, in preparation.

Rutherford, M.J., and Hill, P.M. (1993). Magma ascent rates from amphibole breakdown:

An experimental study applied to the 1980-1986 Mount St. Helens eruptions. Journal of

Geophysical Research, 98, 19667-19685.

Sarna-Wojcicki, A., Waitt, R., Woodward, M., Shipley, S. and Rivera, J. (1982).

Premagmatic ash erupted from March 27 through May 14, 1980-Extent, mass, volume

and composition. In Lipman, P. and Mullineaux, D. (Eds). The 1980 eruptions of Mount

St. Helens, Washington. US Geological Survey Professional Paper, 1250,. 569-576.

Sarna-Wojcicki, A., Meyer, C., Woodward, M., and Lamothe, P. (1982). Composition of

air-fall ash erupted on May 18, May 25, June 12, July 22, and August 7. In Lipman, P.

and Mullineaux, D. (Eds.). The 1980 eruptions of Mount St. Helens, Washington. US

Geological Survey Professional Paper, 1250, 667-682.

Schiavi, F., Tiepolo, M., Pompilio, M., Vannucci, R., Tracking magma dynamics by

Laser Ablation (LA)-ICPMS trace element analysis of glass in volcani ash: the 1995

activity of Mt. Etna. Geophysical Research Letters, in press.

Scott, W. (2006). Overview of the 2004 eruption of Mount St. Helens. US Geological

Survey Professional Paper, in preparation.

218

Streck, M. (2006) Plagioclase zoning in dacites of the 2004-2005 eruption – implications

for magmatic processes. US Geological Survey Professional Paper, in preparation.

Sparks, R.S.J., Bursik, M.I., Carey, S.N., Gilbert, J.S., Glaze, L.S., Sigurdsson, H., and

Woods, A.W. (1997). Volcanic Plumes. J. Wiley and Sons, New York.

Swanson, S., Harbin, M., and Riehle, J. (1995). The 1992 eruptions of Crater Peak vent,

Mount Spurr volcano, Alaska. US Geological Survey Bulletin 2139, 129-137.

Swanson, S., Nye, C., Miller, T., and Avery, V. (1994). Geochemistry of the 1989-1990

eruption of Redoubt Volcano: part II. Mineral and glass chemistry. Journal of

Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 62, 4453-468.

Taddeucci, J., Pompilio, M., and Scarlato, P. (2002). Monitoring the explosive activity of

the July-August 2001 eruption of Mt. Etna (Italy) by ash characterization. Geophysical

Research Letters, 29, 8, 1230, 10.1029/2001GL014372.

Thomas, E., Varekamp, J., and Busheck P. (1982). Zinc enrichment in the phreatic ashes

of Mt. St. Helens, April 1980. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 12,

339-350.

Thornber, C.R. (2006a). From dome to dust: shallow crystallization and fragmentation of

conduit magma during the 2004-2006 dome extrusion of Mount St. Helens, WA. US

Geological Survey Professional Paper, in preparation.

Thornber, C.R. (2006b). Complex P,T history of amphiboles in the 2004-2006 eruption

of MSH. US Geological Survey Professional Paper, in preparation.

Watanabe, K., Danhara, T., Watanabe, K., Terai, K., and Yamashita, T. (1999). Juvenile

volcanic glass erupted before the appearance of the 1991 lava dome, Unzen volcano,

Kyushu, Japan. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research, 89, 113-121.

219

CHAPTER 6

SUMMARY OF CONCLUSIONS

The overlying objective of this dissertation is to examine the major-, trace-, and

volatile-element and fO2 variability in basaltic melt inclusions from across the Oregon

segment of the Cascade volcanic arc, using microanalytical and experimental techniques,

to evaluate the impact of addition of a subduction component on the genesis of primitive

basalts in the Cascades. The first two chapters of this dissertation are dedicated to melt

inclusion rehomogenization experiments focusing on techniques of rehomogenization and

potential problems that may arise with respect to determining melt composition and

oxidation state. The third chapter details application of the techniques described in

chapters 1 and 2 to Cascade olivine-hosted melt inclusions with regard to determining

compositional variability and oxidation state in order to examine the effects of addition of

a subduction component to the subarc mantle.

In the first chapter of this dissertation, heating experiments on olivine-hosted melt

inclusions from a forearc shoshonitic basalt in the Oregon Cascades (QV03-1) document

a previously unreported phenomenon in melt inclusion rehomogenization studies.

Significant Fe-gain in melt inclusions (up to 21 wt% FeO) is determined to be an artifact

of magnetite dissolution during rehomogenization. Magnetite grains coexisting with melt

did not result from crystallization of the inclusion and likely are found to coexist with

melt because of 1) co-entrapment of melt and magnetite during crystallization since early

crystallization of a spinel phase is predicted by the higher water contents of the melt

inclusions, or 2) forming as a result of hydrogen diffusion out of the water rich inclusions

220

during slow cooling. Crystallization of a magnetite dust has been observed as a result of

hydrogen diffusion however not to the extent reported here (Danyushevksy et al., 2002).

These experiments illustrate the importance of having reasonable constraints on the

oxidation state, liquidus temperature of the melt, and water content prior to

rehomogenization. Additionally, since magnetite grains in these melt inclusions had

formed prior to, rather than as a result of rehomogenization, care must be taken to avoid

potentially problematic melt inclusions when rehomogenization is necessary.

Techniques and problems associated with determination of sulfur speciation and

oxidation state in olivine-hosted melt inclusions are detailed in the second chapter of this

dissertation. Utilizing naturally quenched and crystalline melt inclusions, heating

experiments are used to determine the variation in sulfur speciation observed in melt

inclusions resulting from natural magmatic processes and rehomogenization and analysis.

x

In naturally quenched melt inclusions, degassing and hydrogen diffusion have the

greatest potential to alter melt oxidation states. While hydrogen diffusion out of

the inclusion will result in oxidation of the melt, degassing may either oxidize or

reduce the inclusion, depending on the initial melt oxidation state.

x

Fractional crystallization (oxidation) or melting (reduction) and Fe-loss due to the

re-equilibration of the inclusion and host (oxidation) may alter the melt oxidation

state, albeit to a lesser extent than degassing or hydrogen diffusion.

x

These rehomogenization experiments have shown that at short experimental run

times (~10 minutes) and at temperatures that reproduce the original entrapment

conditions, melt oxidation states can be accurately determined once other

221

variables (degassing, hydrogen diffusion, crystallization, and Fe-loss) have been

accounted for.

Applying sulfur speciation measurement techniques to naturally quenched and

rehomogenized melt inclusions (in conjunction with major-, trace-, and volatile-element

variability) from basaltic lavas in the Oregon Cascades allows for several overlying

conclusions to be drawn with regard to (1) impact of a subduction component from the

Juan de Fuca plate and (2) basalt petrogenesis in the Cascade volcanic arc.

x

The overall range in basaltic fO2 is from less than -0.25 log units to +1.9 log units

(> 2.25 log units) relative to the FMQ oxygen buffer and that this range is

believed to be representative of the overall variation in mantle source fO2.

x

OIB-like and shoshonitic basalts have the greatest across arc geochemical

variations while LKT and CAB melt inclusions are relatively similar between the

arc and backarc.

x

Correlation of fluid mobile elements and volatiles with sulfur speciation and fO2

suggests that the addition of a subduction component added to the subarc mantle

(increasing from backarc to forearc) resulted in the generation of more highly

oxidized, fluid-mobile element rich basaltic compositions nearer to the

deformation front.

x

The absence of a significant across-arc variation in CAB melt compositions may

indicate that CAB trace element signatures present in the backarc are the result of

a prior enrichment event and not related to current subduction. High degree

222

melting, shallow mantle segregation depths and low measured fO2 may indicate

that CAB melts re-equilibrated with a more reduced composition prior to eruption

and are therefore not representative of their initial mantle oxidation states

predicted as a result of the addition of a subduction component.

In the final chapter of this dissertation, electron microprobe and LA-ICP-MS

techniques, similar to those utilized on Cascade basaltic melt inclusions, are applied to

phenocryst and glass ash fragments from the 2004 eruption of Mount St. Helens. The

two main objectives of this chapter are to identify the juvenile magmatic component in

early phreatomagmatic explosions (October, 2004) and to track changes in the proportion

and character of juvenile material in the ash over the course of the first year of the

eruption (2004-2005). Several conclusions from trace- and major-element analysis of ash

fragments are summarized here.

x

High Li concentrations in feldspars suggest that the earliest phases of the recent

eruption may have contained a more significant volatile/vapor phase than

originally thought. An increased vapor pressure may have contributed to the

onset of the eruption.

x

Lithium concentrations in feldspars indicate a potential increase in the proportion

juvenile material from October 1 to October 5, 2004, likely tracking the rise of

magma prior to the emergence of hot dacite on October 11, 2004. The high Li

concentration in feldspar is only useful as a tracer for juvenile material during the

beginning stages of the eruption; after ~November 20, 2004 (estimated eruption

223

date of SH305) Li concentrations drop to levels comparable to 1980-86,

suggesting that the volatile enriched magma was only a shallow cap on the larger

magma body.

x

Based on major-element compositions, clean glass in ash samples appear to be

dominantly older volcanic material while juvenile groundmass is typically

crystalline (quartz and feldspar) with localized devitrification and patchy, very

fine vesiculation. This is a significant observation since it is typically the clean

glass that is characterized as juvenile during an eruption.

x

Groundmass textures, grain shapes, and compositional similarities between ash

from vent explosions and dome collapse events and dome fault gouge particles

indicate that the gouge is a predominant source of ash. Heterogeneity observed in

early ash samples correlates with observations that the early extruded dome

material and fault gouge contained a significant proportion of older volcanic

material. Increasing homogeneity of ash with time is consistent with a similar

trend in dome and fault gouge samples.

224

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Albarede, F. (1992). How deep do common basaltic magmas form and differentiate?

Journal of Geophysical Research, 97, 10997-11009.

Anderson, A.T., and Wright, T.L. (1972). Phenocrysts and glass inclusions and their

bearing on oxidation and mixing of basaltic magmas, Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii.

American Mineralogist, 57, 188-216.

Arculus, R.J. (1985). Oxidation status of the mantle: past and present. Annual Review of

Earth and Planetary Sciences, 13, 75-95.

Ariskin, A., Frenkel M., Barmina, G., and Nielsen, R. (1993). COMAGMAT: A Fortran

program to model magma differentiation processes. Computers and Geosciences, 19,

1155-1170.

Armstrong, R.L. (1968). A model for the evolution of strontium and lead isotopes in a

dynamic earth. Reviews of Geophysics, 6 (2), 175-199.

Bacon, C. (1990). Calc-alkaline, shoshonitic, and primitive tholeiitic lavas from

monogenetic volcanoes near Crater Lake, Oregon. Journal of Petrology, 31, 135-166.

Bacon, C., Bruggman, P., Christiansen, R., Clynne, M., Donnelly-Nolan, J., and Hildreth,

W. (1997). Primitive magmas at five Cascade volcanic fields: melts from hot,

heterogeneous sub-arc mantle. The Canadian Mineralogist, 35, 297-423.

Baker, D.R., and Eggler, D. (1983). Fractionation paths of Atka (Aleutians) high-alumina

basalts: constraints from phase relations. Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal

Research, 18, 387-404.

Baker, M.B. Grove, T.L., and Price, R. (1994). Primitive basalts and andesites from the

Mt. Shasta region, N. California: products of varying melt fraction and water content.

Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 118, 111-129.

Ballhaus, C. (1993). Redox states of lithospheric and asthenospheric upper mantle.

Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 114, 331-348.

Ballhaus, C., and Frost, B.R. (1994). The generation of oxidized CO2-beraing basaltic

melts from reduced CH4-bearing upper mantle sources. Geochimica et Cosmochimica

Acta, 58, 4931-4940.

Ballhaus, C., Berry, R.F., and Green, D.H. (1991). High pressure experimental calibration

of the olivine-orthopyroxene-spinel oxygen geobarometer: implications for the oxidation

state of the upper mantle. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 107, 27-40.

225

Ballhaus, C., Berry, R.F., and Green, D.H. (1990). Oxygen fugacity controls in the

Earth’s upper mantle. Nature, 348, 437-440.

Barnes, S.J. (1998). Chromites in komatiites, 1. magmatic controls on crystallization and

composition. Journal of Petrology, 39, 1689-1720.

Berlo, K., Blundy, J., Turner, S., Cashman, K., Hawkesworth, C., and Black, S. (2004).

Geochemical precursors to volcanic activity at Mount St. Helens, USA. Science, 306,

1167-1169.

Beyer, R. (1973). Magma differentiation at Newberry Crater in central Oregon. Ph.D.

Thesis, University of Oregon, Eugene, Oregon, 93.

Bezos, A., and Humler, E. (2005). The Fe3+/6Fe ratios of MORB glasses and their

implications for mantle melting. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 69, 711-725.

Bindeman, I.N., Davis, A.M., and Drake, M.J. (1998). Ion microprobe study of

plagioclase-basalt partition experiments at natural concentration levels of trace elements.

Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 62, 1175-1193.

Borg, L.E., Blichert-toft, J., and Clynne, M.A. (2002). Ancient and modern subduction

zone contributions to the mantle sources of lavas from the Lassen region of California

inferred from Lu-Hf isotopic systematics. Journal of Petrology, 43, 705-723.

Borg, L.E., Clynne, M.A., and Bullen, T.D. (1997). The variable role of slab-derived

fluids in the generation of a suite of primitive calc-alkaline lavas from the southernmost

Cascades, California. The Canadian Mineralogist, 35, 425-452.

Bostock, M., Hyndman, R., Rondenay, S., and Peacock, S. (2002). An inverted

continental Moho and serpentinization of the forearc mantle, Nature, 417, 536-538.

Brandon, A.D., and Draper, D.S. (1996). Constraints on the origin of the oxidation state

of mantle overlying subduction zones: an example from Simcoe Washington, USA.

Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 60, 1739-1749.

Carmichael, I.S.E., and Ghiorso, M.S. (1986). Oxidation-reduction relations in basic

magma: a case for homogenous equilibria. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 78, 200210.

Carmichael, I.S.E., and Ghiorso, M.S. (1990). The effect of oxygen fugacity on the redox

state of natural liquids and their crystallizing phases. In: Nicholls J., and Russel, J.K.

(Eds.), Modern Methods of Igneous Petrology: Understanding Magmatic Processes.

Reviews in Mineralogy 24, 191-212.

226

Carroll, M.R., and Rutherford, M.J. (1988). Sulfur speciation in hydrous experimental

glasses of varying oxidation state: Results from measured wavelength shifts of sulfur Xrays. American Mineralogist 73, 845-849.

Carroll, M.R., and Webster, J.D. (1994). Solubilities of sulfur, noble gases, nitrogen,

chlorine, and fluorine in magmas. In Carroll, M.R., and Holloway, J.R. (Eds.), Volatiles

in Magmas. Reviews in Mineralogy 30, 231-279.

Cashman, K., Sturtevant, B., Papale, P., and Navon, O. (2000). Magmatic fragmentation.

In: H. Sigurdsson (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Volcanoes. Academic Press, London. 421-430.

Cashman , K., and Hoblitt, R. (2004). Magmatic percursors to the 18 May 1980 eruption

of Mount St. Helens, USA. Geology, 32, 2, 141-144.

Catchings, R.D., and Mooney, W.E. (1988). Crustal structure of east central Oregon:

relation between Newberry volcano and regional crustal structure. Journal of Geophysical

Research, 93, 10081-10094.

Cervantes, P., and Wallace, P.J. (2003). The role of H2O in subduction zone magmatism:

New insights from melt inclusions in high-Mg basalts from Central Mexico. Geology, 31,

235-238.

Christie, D.M., Carmichael, I.S.E., and Langmuir, C.H. (1986). Oxidation states of midocean ridge basalt glasses. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 79, 397-411.

Churikova, T., Dorendorf, F., and Worner, G. (2001). Sources and fluids in the mantle

wedge below Kamchatka, evidence from across-arc geochemical variation. Journal of

Petrology, 42, 1567-1593.

Clynne, M.A., and Borg, L.E. (1997). Olivine and chromian spinel in primitive calcalkaline and thoeiitic lavas from the southernmost Cascade range, California: a reflection

of relative fertility of the source. The Canadian Mineralogist, 35, 453-472.

Cottrell, E., Spiegelman, M., and Langmuir, C.H. (2002). Consequences of diffusive

reequilibration for the interpretation of melt inclusions. Geochemistry, Geophysics,

Geosystems 3, 10.1029/2001GC000205.

Conrey, R., Sherrod, D., Hooper, P., and Swanson, D. (1997). Diverse primitive magmas

in the Cascade arc, Northern Oregon and Southern Washington. The Canadian

Mineralogist, 35, 367-396.

227

Conrey, R., Sherrod, D., Hooper, P., and Swanson, D. (1997). Diverse primitive magmas

in the Cascade arc, Northern Oregon and Southern Washington: The Canadian

Mineralogist, 35, 367-396.

Conrey, R.M., Taylor, E.M., Donnelly-Nolan, J.J., Sherrod, D. (2002). North-Central

Oregon Cascades: exploring petrologic and tectonic intimacy in a propagating intra-arc

rift. In: Field Guide to Geologic Processes in Cascadia (ed. G. Moore). Oregon

Department of Geology and Mineral Industries Special Paper 36, 47-90.

Danyushevsky, L. V., Della-Pasqua, F.N., and Sokolov, S. (2000). Re-equilibration of

melt inclusions trapped by magnesian olivine phenocrysts from subduction-related

magmas: petrological implications. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 138, 6883.

Danyushevsky, L. V., McNeill, A.W., and Sobolev, A. (2002). Experimental and

petrological studies of melt inclusions in phenocrysts from mantle-derived magmas: an

overview of techniques, advantages and complications. Chemical Geology, 183, 5-24.

Davidson, J. (1996). Deciphering mantle and crustal signatures in subduction zone

magmatism. In: G. Bebout, D. School, S. Kirby, and J. Platt (Eds.). Subduction Top to

Bottom. American Geophysical Union Monograph 96, 251-262.

Davies, J.H., and Stevenson, D.J. (1992). Physical model of source region of subduction

zone volcanics. Journal of Geophysical Research, 97, 2037-2070.

Deer, W.A., Howie, R., and Zussman, J. (1999). An introduction to the rock-forming

minerals (2nd edition). Pearson Education Limited, Essex, England. 696.

De Hoog, J.C.M., Hattori, K.H., and Hoblitt, R.P. (2004). Oxidized sulfur-rich mafic

magma at Mount Pinatubo, Philippines. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology 146,

750-761.

Duncan, R.A., Hooper, P.R., Rehacek, J., Marsh, J.S. and Duncan, A.R. (1997). The

timing and duration of the Karoo igneous event, southern Gondwana. Journal of

Geophysical Research, 102, 18127-18138.

Duncan, R.A. and Keller, R.A. (2004). Radiometric ages for basement rocks from the

Emperor Seamounts, ODP Leg 197. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, doi:

10.1029/2004GC000704.

Fialin, M., Bezos, A., Wagner, C., Magnein, V., and Humler, E. (2004). Quantitative

electron microprobe analysis of Fe3+/6Fe: Basic concepts and experimental protocol for

glasses. American Mineralogist 98, 654-662.

228

Friedman, J.D., Olhoeft, G.R., Johnson, G.R., and Frank, D. (1982). Heat content and

thermal energy of the June dacite dome in relation to total energy yield, May-October

1980. In Lipman, P. and Mullineaux, D. (Eds.), The 1980 eruptions of Mount St. Helens,

Washington. US Geological Survey Professional Paper, 1250, 557-567.

Gaetani, G.A., and Grove, T.L. (1998). The influence of water on melting of mantle

peridotite. Contributions to Mineralogy and Petrology, 131, 8309-8318.

Gaetani, G. A. and Watson, E.B. (2000). Open-system behavior of olivine-hosted melt

inclusions. Earth and Planetary Sciences, 183, 27-41.

Ghiorso, M.S., and Carmichael, I.S.E. (1987). Modeling magmatic systems: petrologic

applications. In Thermodynamic modeling of geological minerals, fluids and melts, I.S.E.

Carmichael and H.P. Eugster (eds.), Reviews in Mineralogy, 17, 467-499.

Grove, T.L., Parman, S.W., Bowring, S.A., Price, R.C., and Baker, M.B. (2003). The role

of an H2O-rich fluid component in the generation of primitive basaltic andesites and

andesites from the Mt. Shasta region, N. California. Contributions to Mineralogy and

Petrology, 142, 375-396.

Guffanti, M., and Weaver, C. (1988). Distribution of late Cenozoic volcanic vents in the

Cascade range: volcanic arc segmentation and regional tectonic considerations: Journal of

Geophysical Research, 93, 6513-6529.

Harris, R., Iyer, H., and Dawson, P. (1991). Imaging the Juan de Fuca plate beneath

southern Oregon using teleseismic P-wave residuals. Journal of Geophysical Research,

96, 19879-19889.

Harry, D.L., and Green N.L. (1999). Slab dehydration and basalt petrogenesis in

subduction systems involving very young oceanic lithosphere. Chemical Geology, 160,

309-333.

Hauri, E. H. (2002). SIMS analysis of volatiles in silicate glasses, 2: isotopes and

abundances in Hawaiian melt inclusions. Chemical Geology, 183, 115-141.

Hedenquist, J.W., and Lowenstern J.B. (1994). The role of magmas in the formation of

hydrothermal ore deposits. Nature 370, 519-527.

Heiken, G. (1972). Morphology and Petrography of volcanic ashes. GSA Bulletin, 83,

1961-1988.

Higgins, M. (1973). Petrology of Newberry Volcano, Central Oregon. Geological Society

of America Bulletin, 84, 455-487.

229

Hochstaedter, A.G., Gill, J.B., Taylro, B., Ishizuka, O., Yuasa, M., and Morita, S. (2000).

Across-arc geochemical trends in the Izu-Bonin arc: constraints on source composition

and mantle melting. Journal of Geophysical Research, 105, 495-512.

Hochstaedter, A., Gill, J., Peters, R., P, B., Holden, P., and Taylor, B. (2001). Across-arc

geochemical trends in the Izu Bonin arc: Contributions from the subducting slab: Gcubed, 2, 2000GC000105.

Hofmann, A.W. and White, W.M. (1982). Mantle plumes from ancient oceanic crust.

Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 57, 421-436.

Houghton, B. Wilson, C., Smith, R., and Gilbert, J. (2000). Phreatoplinian eruptions. In

H. Sigurdsson (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Volcanoes. Academic Press, London. 513-526.

Imai, A., Listanco, E.L., and Fujii, T. (1993). Petrologic and sulfur isotopic significance

of highly oxidized and sulfur-rich magma of Mt. Pinatubo, Philippines. Geology 21, 699702.

Jensen, R.A. (2000). Roadside guide to the geology of Newberry Volcano.

CenOreGeoPub, Bend, Oregon, 168.

Johnson, D.M., Hooper, P.R., and Conrey, R. M. (1999). XRF analysis of rocks and

minerals for major and trace elements on a single low dilution Li-tetraborate fused bead.

Advances in X-ray Analysis, 41, 843-867.

Jordan, B.T. (2005). Age-progressive volcanism of the Oregon High Lava Plains;

overview and evaluation of tectonic models. In: G.R. Foulger, J.H. Natland, D.C. Presnal,

and D.L. Anderson (eds.). Plates, Plumes and Paradigms. Geological Society of America

Special Paper, 388, 503-515.

Jordan, B.T. (2001). Basaltic volcanism and tectonics of the High Lava Plains,

southeastern Oregon. Ph.D. Thesis, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, 218.

Jugo, P.J., Luth, R.W., and Richards, J.P. (2005a). Experimental data on the speciation of

sulfur as a function of oxygen fugacity in basaltic melts. Geochimica et Cosmochimica

Acta 69, 497-503.

Jugo, P.J., Luth, R.W., and Richards, J.P. (2005b). An experimental study of the sulfur

content in basaltic melts saturated with immiscible sulfide or sulfate liquids at 1300°C

and 1.0 GPa. Journal of Petrology 46, 783-798.

Kamenetsky, V.S., Crawford, A.J. and Meffre, S. (2001). Factors controlling chemistry

of magmatic spinel: an empirical study of associated olivine, Cr-spinel and melt

inclusions from primitive rocks. Journal of Petrology, 42, 655-671.

230

Kamenetsky, V. S., Crawford, A.J., Eggins, S.M., and Muehe, R. (1997). Phenocryst and

melt inclusion chemistry of near-axis seamounts, Valu Fa Ridge, Lau Basin: insight into

mantle wedge melting and the addition of subduction components. Earth and Planetary

Science Letters, 151, 205-223.

Karig, D.E. and Kay, R.W. (1981). Fate of sediments on the descending plate at

convergent margins. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London A, 301,

233-251.

Katsura, T., and Muan, A. (1964). Experimental study of equilibria in the system FeOFe2O3-Cr2O3 at 1300ºC. Transactions of the American Institute of Mining and

Metallurgical Engineers, 230, 77-84.

Kent, A.J.R., and Elliot, T.R. (2002). Melt inclusions from Mariana arc lavas:

Implications for the composition and formation of island arc magmas. Chemical

Geology, 183, 265-288.

Kent, A.J.R., Rowe, M.C., Thornber, C., and Pallister, J. (2006). Laser ablation ICP-MS

measurements of trace-element and Pb isotopic compositions of Mt St Helens dome

material from 2004-2005: Implications for magmatic origin and evolution Li

concentrations. US Geological Survey Professional Paper, in preparation.