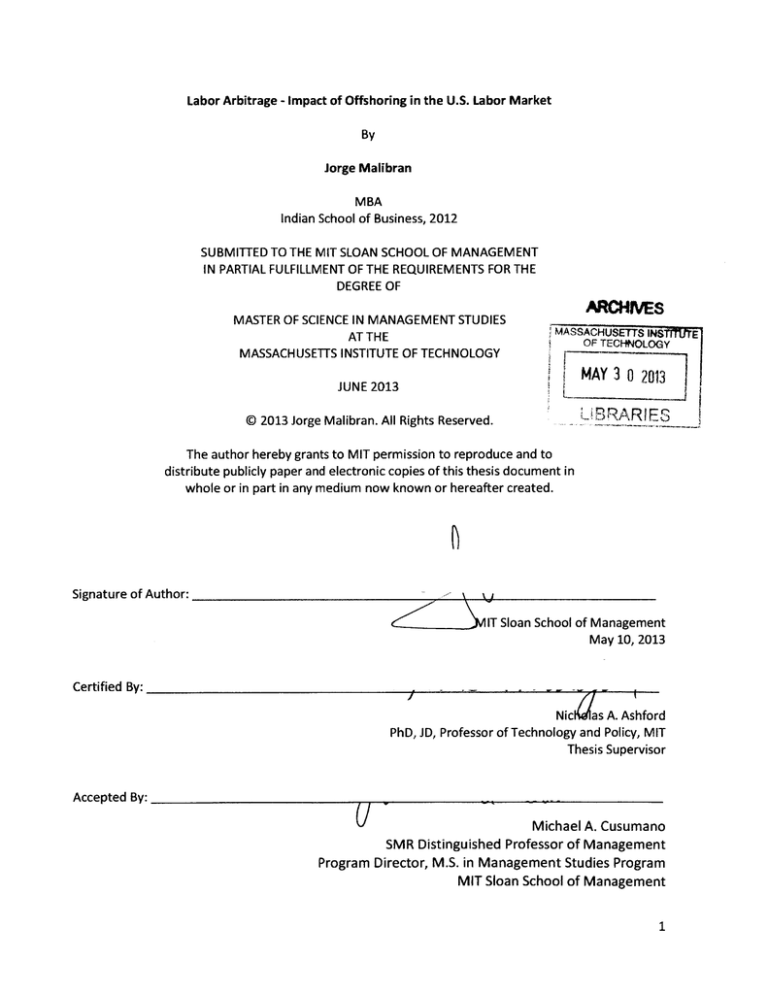

Labor Arbitrage - Impact of Offshoring in the U.S. Labor Market

By

Jorge Malibran

MBA

Indian School of Business, 2012

SUBMITTED TO THE MIT SLOAN SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE

DEGREE OF

MASTER OF SCIENCE IN MANAGEMENT STUDIES

AT THE

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

ARCHNVES

MASSACHUSETS INSi

OF TECHNOLOGY

MAY 3 0 2013

JUNE 2013

3R

@ 2013 Jorge Malibran. All Rights Reserved.

~R!E S

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to

distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in

whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created.

h'

Signature of Author:

IT Sloan School of Management

May 10, 2013

Certified By:

Nicdas A. Ashford

PhD, JD, Professor of Technology and Policy, MIT

Thesis Supervisor

Accepted By:

(I

Michael A. Cusumano

SMR Distinguished Professor of Management

Program Director, M.S. in Management Studies Program

MIT Sloan School of Management

1

E

2

Labor Arbitrage - Impact of Offshoring in the U.S. Labor Market

By

Jorge Malibran

Submitted to the MIT Sloan School of Management on May 10, 2013 in partial

fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Management

Studies

Abstract

The rapid growth of offshoring has ignited a contentious debate over its impact on the US labor

market. Between 1983 and 2002, the United States economy lost 6 million jobs in manufacturing and

income inequality increased sharply [Ebenstein, 2011]. Today due to the falling costs of transportation,

coordination and communication this tendency is accelerating affecting both white and blue collar

workers. While there many papers that analyze the productivity increase due to offshoring practices

[Mitra, 2007], [Global Insight, 20041, [Houseman, 2010], most of them just assume that this

improvement is automatically translated into lower prices therefore benefiting consumers. Nevertheless

this assumption only holds in price competitive markets, which is not always the case.

In this paper I will challenge the assumption of price competitive markets and argue how offshoring

increases within-country income inequality. In addition I will analyze the aggregated effect of offshoring

in the U.S. economy through both empirical and theoretical approaches.

Thesis Supervisor: Nicholas A. Ashford

Title: PhD, JD, Professor of Technology and Policy, MIT

3

4

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, I would like to thank my thesis supervisor, Professor Nicholas Ashford, for his

valuable advice, dedication and support during this year. With his guidance, I have been able to navigate

through the vast literature and focus on the key areas for research. His vast knowledge and incredible

insights have allowed me to understand and analyze with much more depth such a complex topic as the

macroeconomic implications of offshoring.

I am also grateful to the MSMS program, in especially to Julia N. Sargeaunt and Chanh Q. Panh, for their

support and encouragement throughout this research process and the whole academic year. Their help

and commitment was inspiring and kept me focused until the last minute. I would also like to thank

them for organizing thesis workshops during their free time, these meetings helped me regain focus and

improve my writing style. I would also like to thank all of the MSMS 2012 students for their support.

It is difficult to overstate my gratitude to Cristina, my wife, for her tireless assistance and unconditional

understanding, her help and support during this year have kept me sane and focused. She has really

been my compass and my support during all this time.

Finally, I owe my deepest gratitude to my parents, Rosa Angel and Jorge Malibran, for encouraging me

and making it possible to pursue this degree, without their support this amazing learning adventure

would not have happened.

5

6

Table of Contents

9

Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................

Evidence from U.S. M anufacturing.............................................................................................................16

Offshoring Productivity Gains..........................................................................................................

...---19

Productivity Gains and CPI......................................................................................................................19

Productivity Gains and W ages ................................................................................................................

21

Productivity Gains and Com pany Profits ............................................................................................

22

M acroeconom ic Im plications......................................................................................................................24

Offshoring - Fading Advantage?..................................................................................................................27

Conclusion...................................................................................................................................................

31

Directions for Further Research..................................................................................................................32

Bibliography ................................................................................................................................................

34

Appendix I: Imports of Goods and Manufacturing Jobs - Correlation Analysis ......................................

37

Appendix II: Personal Incom e vs. Corporate Profit Growth Analysis......................................................

38

7

Table of Figures

Figure 1: Average monthly wage in USD (United Nations' International Labor Organization)..............10

Figure 2: Median programmer annual salary (www.payscale.com)......................................................

10

Figure 3: Worldwide corporate tax evolution (Price Waterhouse Coopers)......................................... 12

Figure 4: Baltic Dry Index 2009-2013 (Bloomberg.com)..........................................................................13

Figure 5: Offshore job loss projection (Forrester Research Inc.)..........................................................

13

Figure 6: U.S total value of imports and exports of goods and services (U.S. Census Bureau)..............17

Figure 7: U.S. manufacturing employment (Bureau of Labor Statistics)................................................17

Figure 8: Industrial production Vs. manufacturing jobs (Bureau of Labor Statistics).............................18

Figure 9: Consumer price index Vs. GDP Deflator (Bureau of Labor Statistics)......................................20

Figure 10: CEO pay vs. company earnings (Forbes.com)......................................................................22

Figure 11: Corporate profit vs. personal income growth (Bureau of Economic Analysis)......................23

Figure 12: Offshoring value potential accrued to the U.S. (McKinsey Global Institute)........................24

Figure 13: Share of income, by income group, growth since 1979 (Congressional Budget Office) .....

26

Figure 14: Baltic Dry Index 2011-2013 (Bloomberg.com).......................................................................28

Figure 15: Manufacturing outsourcing cost index (Alix Partners)..........................................................28

Figure 16: USD/CNY,MXNINR exchange rates (Google Finance)..........................................................29

Figure 17: Companies' intentions to change manufacturing source (The Economist)...........................30

Figure 18: Correlation analysis between imports of goods and manufacturing jobs............................. 37

Figure 19: Capital gains vs. personal income since 1976 (Bureau of Economic Analysis).....................38

Figure 20: Personal income vs. corporate profit growth over time (Bureau of Economic Analysis)..........39

8

Introduction

Offshoring is the term used to describe the relocation by a company of a business process from

one country to another-typically from developed countries to developing ones. The term was originally

used in financial economics, since many offshore financial centers are British colonial islands located offshore of the mainland such as Singapore, Hong-Kong and the Caribbean Islands. Today the term

offshoring has extended from its solely financial meaning to the term goods offshoring and more

recently services offshoring.

It is important to note that offshoring only implies the relocation of a business process to another

country and not contracting out a process to a third party organization, which is the definition of

outsourcing. Therefore there can be two types of offshoring practices:

-

Captive Offshoring (Foreign Direct Investment): production of goods or services effected or

partially or totally transferred abroad within the same group of enterprises. This implies an

enterprise transferring some of its activities to its foreign affiliates. These affiliates may

already exist or have been created from scratch (greenfield affiliates).

-

Offshore Outsourcing: partial or total transfer of the production of goods or services abroad

to a non-affiliated enterprise.

One of the main drivers of Offshoring has traditionally been cost reduction, mainly due to lower labor

cost in developing countries. Companies can immediately reduce their labor cost by laying off

employees at home and hiring workers in developing countries were wages are much lower than in the

U.S1 . (see figure 1). Taking advantage of wage differentials in different countries to reduce labor costs is

denominated "labor arbitrage".

1While average monthly wages do not provide a good estimation of how much a company can save by relocating

to a country, it is useful to illustrate the potential of labor arbitrage.

9

Average Monthly Wage (USD)

3,500

2,5001M-

L

5W

-T

-T

0

Figure 1: Average monthly wage in USD '(United Nations' International Labor Organization)

For example a U.S. software company that decides to offshore the development of their new product to

India, can reduce their development cost by up to 84 percent as the average developer in India earns six

times less than his U.S. peer (see figure 2).

Median Programmer Annual

Salary

70,000

-

60,000

50,000

40,000

30,000

-

2o'000

U.S.

Ireland

China

Russia

India

Figure 2: Median programmer annual salary (www.payscale.com)

While labor arbitrage is the main driver of offshoring, companies also find other benefits from relocating

business process abroad:

10

Access to talent: for certain professions there is a greater availability of workers overseas.

Some countries even promote the specialization of their labor force, very much following

the Ricardian precepts of comparative advantage (e.g., China with manufacturing or India

with IT enabled services).

The lack of skilled workers in the U.S. is becoming an important driver of offshoring. While

the average education of the U.S. workforce is declining, companies require more skilled

workers than ever. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics the U.S. experienced a

shortage of 7 million skilled workers and this shortage is expected to rise to 21 million skilled

workers by 2020.

Reduction of legal exposure: employing offshore staff reduces legal exposure to

employment liabilities and environmental costs. Developing countries, main offshoring

destinations, usually have laxer regulations and safety standards, allowing companies to

reduce their legal liabilities and compliance costs.

Operational flexibility: offshoring reduces hiring and termination costs, allowing companies

to quickly expand and contract their overseas labor force in accordance with business

cycles.

Lower tax rates: companies can take advantage of lower corporate tax rates overseas to

reduce their tax liabilities. Currently the U.S. is the country with the second highest

corporate tax rate in the world, only after United Arab Emirates, and it has consistently had

higher corporate tax rates than the rest of OECD countries and main offshoring destinations

(see figure 2). Due to this comparatively high corporate tax rate, corporations find incentives

to open subsidiaries in low taxed countries and redirect their profits there.

11

Corporate Tax Rate Evolution

45

40

-US

35

-OECD

average

Global average

-

China

25

20

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

Figure 3: Worldwide corporate tax evolution (Price Waterhouse Coopers)

-

Proximity to clients: companies may decide go offshore to be closer to their customers. This

proximity allows companies to reduce their shipping costs and improve their time response

serving overseas markets. The high economic growth and increased purchasing power of

these markets are currently driving many offshoring practices.

-

Focus: by offshoring certain processes, companies can free resources to focus on more

valuable activities. This shift towards core competences allows firms to dedicate more time

to their strengths, deriving the maximum benefit from their talents.

Offshoring has been a common practice over the past 50 years. As early as 1960, US forms offshored the

labor-intensive stages of semiconductor manufacturing to Asia in order to make use of low-cost,

unskilled foreign labor [GAO, 2006].

Today the falling costs of transportation are allowing firms to reduce the inherited costs of offshoring

production processes. We can see in the Baltic Dry Index 2, how the average price of shipping dry goods

has been falling for the last five years (see figure 3). Nevertheless several authors [Pasti, 2011],

[McCarthy, 2006] argue that this extraordinarily low transportation costs will not last as energy prices

will rise in the near future.

2The

Baltic Dry Index (BDI) is an assessment of the average price to ship raw materials (such as coal, iron ore,

cement and grains) on a number of shipping routes (about 50) and by ship size. It is thus an indicator of the cost

paid to ship raw materials on global markets and an important component of input costs.

12

Figure 4: Baltic Dry Index 2009-2013 (Bloomberg.com)

In addition the internet has also reduced coordination and communication costs, allowing firms in rich

countries to fragment their production process and offshore an increasing share of the value chain to

low-wage countries.

This increase in offshoring practices has been documented by U.S. institutions. In their last research for

the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Forrester Research Inc., projected a total of 3.3 million jobs offshored

in 2015 (see figure 4).

While it is difficult to estimate the exact numbers, there is no doubt that

offshoring has a significant impact on U.S. labor market.

Offshore Job Loss Projection

2003

2004

2005

a Number of US Jobsmoving

2006

2007

offshore by 2015, in millions

2008

2010

2015

0

1

2

3

4

Figure 5: Offshore job loss projection (Forrester Research Inc.)

13

The rapid growth of offshoring practices has ignited a contentious debate over its impact on the U.S.

economy and more specifically on the U.S. labor market. This public debate motivated U.S. Congress to

take action. On October 22, 2004 the Congress passed the "American Jobs Creation Act of 2004" which

contains a provision to encourage profit repatriation back to the U.S. by domestic multinationals. Yet the

evidence linking offshore activities with falling domestic demand due to reductions in U.S. purchasing

power is still under dispute.

Several studies argue that there are no employment losses due to offshoring activities. Borga in her

paper "Trends in Employment at U.S. Multinational companies" [Borga, 2006] and Desai, Foley and

Hines in "Foreign Direct Investment and Domestic Economic Activity" [Desai, 2005] argue that expansion

of U.S. multinationals abroad stimulates job growth at home. In the same line, Mankiw and Swagel

concluded that foreign activity does not crowd out domestic activity [Mankiw, 2006].

A second group of studies reached the opposite conclusion. Brainard and Riker found evidence that

foreign affiliate employment substitutes at the margins for U.S. parent employment, and that there is

much stronger substitution between workers at affiliates in alternative low wage locations [Brainard,

2001]. Muendler and Becker reach similar conclusions analyzing German manufacturing industry

[Muendler, 20061.

These studies and many others focus their research on the macroeconomic implications of offshoring

practices. Most of their arguments can be grouped under one of the following categories:

Positive effects of offshoring on employment:

-

Growth in consumers' disposable incomes: by offshoring certain business processes

companies can reduce their operating costs and improve total factor productivity. In price

14

competitive markets these costs reductions could be translated into lower prices for final

goods and services, therefore increasing consumers' surplus.

The growth in consumers' surplus could increase consumption which will have a positive

impact on employment if it is mainly oriented towards demand for goods and services

produced in that same country. It is important to note that the new jobs created due this

increased demand may be completely different to the ones offshored.

Improved competitiveness and productivity in enterprises: the productivity increases due

to offshoring help enterprises become more competitive in the global market. Thanks to the

earlier mentioned cost reductions companies can decide to either reduce their prices to

serve a bigger market, or maintain previous prices and increase their profit margins. Both

strategies will have a positive effect on their profits.

The impact on employment will depend greatly on the strategy adopted by the enterprise

and the macro-economic environment.

Export growth: offshoring practices could influence exports in two ways. Empirical studies

show that foreign investment often complements trade and generates additional exports,

and indirectly job creation [Fontagn&, 1999]. In addition, the growth in incomes in the

offshore countries can create demand for products produced locally, affecting exports and

local employment.

Control of inflation: the costs reductions due to offshoring, if transferred to final prices, can

contribute to better control of inflation and a reduction of consumer prices. This control

over inflation allows flexible monetary policies and lower real interest rates which indirectly

stimulate investment and job creation.

15

Negative effects of offshoring on employment:

-

Fall in real wages: companies deciding to offshore certain business processes could see their

bargaining power increase when negotiating with local workers. Local labor will now need to

compete with their overseas counterparts, usually low-wage countries.

-

Deterioration in terms of trade: offshoring generally helps the economy of a country to the

extent that it leads to a fall in the price of imported goods or services. Nevertheless, this

could cause a deterioration of that country's terms of trade, mostly if the exported goods or

services are in a similar range.

-

Loss of tax revenues: companies who decide to offshore operations will stop generating

income taxes at home. In addition companies with operations overseas can move profit to

their subsidiaries in countries with lower corporate taxes, through appropriate price transfer

strategies.

-

Regional effects: even when offshoring has a minor effect at national level, it can have

serious consequences to particular regions, especially when its activity is the major

economic driver of the region. In this case workers will need to transition to other industries

or business with a possible reduction on their real wages [Ebenstein, 2011].

Evidence from U.S. Manufacturing

Arguably the most important development for the U.S. manufacturing industry in recent years

has been the rapid growth of trade. After being almost flat during the 1990s, the total value of imports

and exports of goods and services jumped from roughly 22 percent of GDP to 29 percent in 2010 (see

figure 5). Most of this increase is attributable to the growth of nonoil good imports.

16

U.S. Total Value of Imports and Exports of Goods and Services

32.00%

5,000,000

-

4,500,000

30.00%

4,000,000

28.00%

3,500,000

1 3,000,000

"

----

---

2,500,000

E

26.00%

-

-

2,000,000

Total Value in

-

%ofGDP

$millions

24.00

24.00%

--

L500,000----

-

22.00%

500,000

20.00%

0

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

Figure 6: U.S total value of imports and exports of goods and services (U.S. Census Bureau)

This increase of nonoil imports explains why the U.S. manufacturing industry has lost more than six

million jobs in the last 30 years (see figure 6). Even after the 2001-2002 recession, manufacturing

employment declined by 20 percent, while manufacturing's share of employment in the economy fell

from 14 percent in 1997 to 9 percent in 2010.

Manufacturing Employment

20000

19000

1800

17000

16000

15000

14000

13000

-

--

Manufacturing Jobs in

thousands

12000

1J0u

G o8VA1;s

OG

10000

PT

M~~~

M

~ nMMMcn0

~ M; Ch

W-4"~ V-1M(

araq~o

V4 ol

r-4

a

Figure 7: U.S. manufacturing employment (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

Indeed the correlation between the total value of imports of goods and the number manufacturing jobs

is highly negative, -0.67. A more detailed analysis, including a simple regression model can be found in

Appendix 1.

17

This exodus of manufacturing jobs has also put significant downward wage pressure on U.S.

manufacturing workers, who now have to compete in a global market. In a recent study using current

population surveys, Avraham Ebenstein et al. calculated that a ten percent point increase in occupationspecific exposure to offshoring in low-wage countries is associated with a 0.73 percent decline in real

wages for workers performing routine tasks [Ebenstein, 2011]. In this same study the authors found that

when workers relocate from manufacturing to the service sector, they experience a significant wage

loss, between two and eleven percent.

While the U.S. manufacturing industry saw steep employment declines and significant downward wage

pressure, it also recorded strong output growth (see figure 7). This increase of production was due to

notable gains in manufacturing productivity.

Industrial Production Index Vs. Manuf 3cturing Jobs

,

20%

110

100

- - -

---

18%

- --------

-

-

-

-

-

-

90

80

---

-

162%

16%

--- 4

70

60

10%

-

Manu icturing Employment as

percen tage of all jobs

-- Industrlal Production Index

---40

6E

%

5

I(

bbN0A 45S

0 I

2

.0

20

41'

Figure 8: Industrial production Vs. manufacturing jobs (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

In conclusion, while U.S. manufacturing companies increased their productivity due to offshoring

practices, U.S. manufacturing workers were relegated to other industries. This displacement affected

their average income, lowering it, between two and eleven percent [Ebenstein, 2011]. The question is

who benefits from these productivity increases and how does this displacement of jobs overseas affect

the U.S. economy.

18

Offshoring Productivity Gains

Many studies have demonstrated the positive impact of offshoring practices on companies'

productivity and cost savings. Byrne et al. find sizable cross-country differences in the prices of

semiconductors with identical specifications [Byrne, 2009]. On average, they found that compared to

the U.S., prices were 40 percent lower in China and 25 percent lower in Singapore. Klier and Rubenstein

provided evidence that offshored aluminum production in Mexico was 19 percent cheaper than in the

U.S. [Klier, 20091. Nevertheless, it is not clear how these productivity increases are then propagated to

the economy.

Productivity Gains and CPI

Many studies [Mitra, 20071, [Global Insight, 2004] assume that the cost reductions due to

offshoring processes overseas are mostly translated into lower final product prices. These lower prices

affect equally all consumers who will then translate these savings into the economy in the form of new

consumption. Nevertheless, this assumption only holds for price competitive markets, less

commoditized business find less incentives in propagating this cost reduction into final prices.

Using a hypothetical example; a U.S. phone manufacturer decides to offshore part of its

production to China where wages are 50 percent lower. Because most of the demand for the

phone is local, the company has to ship back all parts manufactured in China, but even

considering the shipping and managing cost the company is able to produce the phones at a 10

percent discount. This cost reduction allows the company to reduce the phone price and at the

same time maintain their margins. This decision would benefit all consumers who will see their

purchasing power increase and will consume more of other local goods and services, which

indirectly will have a positive impact on local employment. But why the company would decide

to reduce the price of the phones? The phone manufacturer is a market leader, the brand

19

provides enough value to de-commoditize the terminal and the pricing has been set to capture

the maximum consumer surplus. Under these circumstances the company has few incentives to

propagate their cost savings into prices.

While commoditized business, like semiconductors or metal parts, were the pioneers of offshoring

practices, today business of all industries are looking to fragment their production process and offshore

an increasing share of the value chain. The offshoring of these decommoditized businesses will have

little impact on consumers surplus and therefore on employment generation. Even if some of the

corporate savings are translated into price declines, this would still not necessarily lead to higher living

standards for American households.

A good indicator of the continued lagging of growth in labor compensation behind growth in

productivity is the persistent gap between inflation in the prices of goods consumed by American

households (CPI) relative to the price of goods produced by American workers (GDPD).

Consumer Price Index Vs. GDP Deflator

800.0

-

------

700.0

50.0

'5400.0

-

300.0

--

C

GDPD

200.0

100.0

O.O

--

19671969197119731975197719791981198319851987198919911993199519971999200120032005200720092011

Figure 9: consumer price Index Vs. GDP Deflator (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

If we analyze both indexes normalized to 1967 price levels, we can see that prices of products produced

overseas and consumed by American families are rising more sharply than the GDPD, which is highly

correlated with U.S. worker wages, over the last three decades. This means that American households

20

tend to consume goods whose prices are rising relatively rapidly and therefore they could reduce their

living standards if the relative consumption of offshored to local products increases.

Nevertheless it is important to note that it is difficult to measure the real impact of offshoring in the CPI

as price declines associated with the shift of production to low-cost countries is only partially captured

in price index [Houseman, 2010]3.

Productivity Gains and Wages

Companies could decide to use the productivity gains achieved due to offshoring practices to

increase their employees' salaries. While plausible there is no economic reason for companies to

increase their employees' wages and we definitely see no evidence of it. Indeed the opposite seems to

be true. Workers at home will now need to compete at a global scale with their overseas counterparts.

This new competition from low wage countries will put downward pressure on local wages.

The same U.S. phone manufacturer who already has offshorde part of its production to China

reducing their operating cost by 10 percent is now evaluating the possibility of offshoring their

quality control process to the same Chinese region. They estimate they can reduce the cost of

this process by 10 percent but they fear the lack of skilled labor in the region so they postpone

the decision. Several months after their U.S. quality control employees ask for their yearly salary

increase but the direction now has fewer incentives to agree to their request. They can just

threaten them with offshoring the whole process to China.

In his book offshoring of American jobs Jagdish Bhagwati and Alan Blinder analyze the impact of

offshorability on occupation wages. By classifying professions by Blinder's offshorability index [Blinder,

Susan N. Houseman et al. in their paper "Offshoring and the State of American Manufacturing" analyzed how

price indexes like CPI do not fully capture the reduction in prices due to offshoring practices. This bias to the input

price indexes is proportional to the growth in share captured by the low-cost supplier and the percentage discount

offered by the low-cost supplier.

3

21

2008] and running a simple wage regression they found out that workers in the most offshorable jobs

were already paying an estimated 13 percent wage penalty, given their educational attainments

[Bhagwhati, 2009].

Companies may also use these productivity increases to increase their executives' compensation, but

again we see no economic reason for it and an analysis from Forbes by Scott de Carlo showed no

evidence, at least in the last decade (see figure 9).

60%

CH$ANGE N TOTAL PAY

s0

40

30

20

t0

0

-to

-20

-30

-40

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

Figure 10: CEO pay vs. company earnings (Forbes.com)

Productivity Gains and Company Profits

Companies could use these productivity gains to increase their profits, and either distribute

them to their shareholders in the form of dividends or keep them in the form of retained earnings.

Companies as profit maximizers would not reinvest the profits acquired due to offshoring practices if

their return over investment is not higher than their cost of capital. Therefore using the productivity

increases to increase profits would be their option by default.

The phone manufacturer has been able to save up to $100 million in operating costs due to the

relocation of its production in China. The CEO is extremely happy and is thinking on how to invest

this money. They already evaluated the possibility of reducing the phone price and increasing

wages, but the CEO finds no incentives in doing that. They do not need to increase production as

22

they do not foresee a rise in demand. He thinks about giving an extraordinary dividend to the

shareholders of the company but as his CFO does not recommend it because in that case he will

need to repatriate these profits and pay an extra 10 percent in taxes, he finally decides to keep

this money abroad and leave it in its Chinese subsidiary balance sheet in the form cash

equivalents, until it is reinvested in places other than the U.S.

The degree to which productivity gains go to enhanced corporate profits is difficult to estimate.

However, there seems to be evidence that companies are using most of their offshoring gains to

improve their bottom lines. Reviewing data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis we can see how

during the last decade corporate sector profits grew three times faster than personal income (see figure

11). While this entire shift in the income distribution is surely not driven by offshoring, this data is

exactly in line with what one would expect if offshoring was already a major feature of the U.S.

economy. A more detailed analysis of this tendency can be found in Appendix II.

Corporate Profit vs. Personal Income Growth

18.00%16.00-14.00%12.00%6

--

10.006

a Corporate

Profit Growth

n Personal Income Growth

8.00%

0.%

1975-2000

2000-2011

Figure 11: Corporate profit vs. personal income growth (Bureau of Economic Analysis)

23

Another useful indicator that can be explained by this lack of reinvestment of corporate profits is the

amount of cash in companies' balance sheets. According to JP Morgan during 2012 companies in the

S&P 500 have increased their cash balances by 14%, reaching a historic high of $1.5 trillion. While this

increase in companies' cash balances is mainly driven by the economic deceleration and financial

instability, it also affected by the use of the profits due to offshoring practices.

Macroeconomic Implications

Many studies have documented the positive impact of offshoring practices on productivity

[Mitra, 2007], [Global Insight, 2004], [Houseman, 2010]. However there is little consensus about how

these productivity gains affect the U.S. labor market. One of the most cited reports, "Offshoring: Is it a

Win-Win Game?" from the McKinsey Global Institute [MGI, 2003] estimated the return over investment

of every dollar offshored between 12 and 14 percent (see figure 11).

Value polentMi to the U.S. from $1of spend offshored to Iada 2002

Dollars

Further value ceation potential through

Increased global competitiveness of

US. business

Multiplier effect of increased national savings

-1.12-1.14

0.4-GA?

0,67

i

0.58nrr,

Savings accrued

to U.S. investors

andor

customers

Import of U.S

goods and

services by

providers in

india

r--A

- -

Transfer of

profits by US.

providers In low*age country

to parent

Tota direct

benefit retained in the US.

Value from U.S.

labor

reemployed*

(conservathe

estirnate)

_y-Current direct benefit*

Potential for

total value

creation in the

U.S. economy

(conservative

estimate)

Potential

future benefit

Estimated based on historical roornploment trends from job b"s through trade in the U.S. economy

Source: McKinsey Global tastitute

FIgure 12: Offshoring value potential accrued to the U.S. (McKinsey Global Institute)

24

The detailed breakdown of these benefits in McKinsey's report is the following:

-

Fifty-eight cents saved in corporate costs: cost savings represent the largest form of

economic value captured. A more competitive cost position will lead to higher profitability,

increased valuations and help keep U.S. companies highly competitive in the world

economy.

-

Five cents due to the U.S. exports to the country where employment has been offshored:

for every dollar of spend offshored, offshore services providers buy an additional goods and

services from the U.S. economy, thereby creating exports and extra revenue for the U.S.

economy. Providers in low-wage countries require U.S. computers, telecommunications

equipment, other hardware and software.

-

Four cents repatriated to U.S. multinationals from the offshored location: Several

providers serving U.S. offshoring market are incorporated in the United States. These

companies could repatriate their earnings back to the U.S. Nevertheless companies find few

incentives for repatriating offshore profits, mainly due to the high corporate tax rates in the

U.S. A good proof of it is the recent debate on tax holidays for corporate profit repatriation

and the more than a $1 trillion of offshore earnings sitting in tax havens based on

Bloomberg's estimations.

-

Forty-six cents on average due to the re-employment of U.S. workers whose jobs have

been offshored: As low value-added service is sourced from overseas, U.S. workers

previously engaged in providing those services are freed up to take other jobs. McKinsey

argues that there is empirical evidence that that services workers find employment more

quickly than do manufacturing workers, primary affected by offshoring practices, and

therefore the shift towards a service oriented economy generates additional value.

25

Although, as services offshoring gains relevance the value due to worker re-employment can

be significantly reduced.

While MGI report is one of the most referenced analyses it fails to demonstrate how the firm-level

benefits due to offshoring practices are translated into net economy-wide gains.

First the numbers of the analysis are most probably biased as it is based on a proprietary data set of selfselected firms that have chosen to offshore some processes specifically because offshoring provided

clear economic gains. Second, the report does not recognize that American workers appear as net

losers. Only if 80 percent of the savings accrued to U.S. companies is transferred to price reductions,

U.S. workers will maintain their purchasing power and as I have discussed in the previous section there

is no evidence that such amount of savings to companies is been translated into lower consumption

prices.

Furthermore, the cost savings in the form of lower wages, economies of scale and proximity to new

markets due to offshoring to low-wage countries is 58 cents, while U.S. workers receive only 47 cents in

labor earnings after the process. This implies a total loss of 11 cents for labor earnings for each dollar of

production that is offshored, money that represents a redistribution of income away from U.S. workers.

This redistribution is in line with the income inequality increase in the U.S. (see figure 12).

Share of Total After-Tax Income, by Income Group, growth since 1979

14(100%

.2

6000%-21st

Lowest Qintile

t8Ofth Percentiles

40A00

81st to 99th Percentiles

-Top

1 Percent

ore%

-20.00%#

-40.00%

-60.00%

Figure 13: Share of Income, by income group, growth since 1979 (Congressional Budget Office)

26

The MGI report also fails to account for the increased imports resulting from offshoring. This is of crucial

importance as the U.S. economy needs to finance these new imports by increasing exports, which could

be instead employed to promote U.S. consumption or investment. By focusing only on the positive

effects of offshoring on companies MGI ignores how the net increase in imports entails hidden costs to

the economy derived from transferring domestic resources to finance increased imports.

Like the MGI, many studies ignore the aggregated effect of increased imports due to offshoring

practices. This increase in imports does not only affect U.S. balance of payments, like Nobel Laureate

Paul Samuelson explained in the Journal of Economic Perspectives, a rapid increase in productivity in

offshore countries can result in a reduction of U.S. income through the terms of trade 4 [Samuelson,

2004].

Offshoring - Fading Advantage?

There has been some discussion recently about the fading benefits of offshoring. In "The

Economist" January 2013 edition there are several articles asserting that companies are rethinking their

offshoring strategies due to lower benefits from offshoring practices. The Economist argues that the

rising shipping costs and the diminishing wage differentials between the U.S. and main offshoring

countries make offshoring practices less appealing and companies are even thinking about reshoring

their offshored business processes. Nevertheless there seems to be little evidence of these phenomena.

The Baltic Dry Index, an indicator of the cost paid to ship raw materials on global markets and an

important component of input costs, is on a downward trend since 2008 and in the last three years it

The "terms of trade" refer to the prices overseas purchasers pay for U.S. exports relative to the prices U.S.

residents pay for imports. If U.S. exports increase prices on foreign markets or U.S. import prices drop, the terms of

trade for the U.S. improve, consumers in the U.S. are able to buy more goods given its current income and

productivity. If on the other hand U.S. exports decrease or imports become more expensive, U.S. terms of trade

deteriorate and therefore U.S. consumers see their purchasing power reduced given current income and

productivity.

4

27

has dropped by 75 percent (see figure 14). This means that the price of shipping goods across the globe

has been decreasing at least during the last three years.

.212

OCT

AM

21R.

AI

CT

K12

APR

.222?

OCT

211

APR

Figure 14: Baltic Dry Index 2011-2013 (Bloomberg.com)

In addition the Economist uses production costs predictions from the 2011 Alix Partners "U.S.

Manufacturing-Outsourcing Index" [Alix Partners, 20111. The index forecasts that the manufacturing in

China will be as expensive as manufacturing in the U.S. by 2015 (see figure 15), eliminating any labor

arbitrage opportunity. Nevertheless these forecasts assume a 30 percent annual wage rate increase in

China, a 5 percent annual appreciation of the Renminbi against the Dollar and a 5 percent annual

increase of shipping costs. While plausible it seems unlikely that all these assumptions will hold for the

next three years.

o

90%

U

o

90%

70%

60%

-

-+.-

U.'(as

200

2006

e

-de- Mexco

23,7 2Y0

..-

Chra

-

-

a

2009 2C!3 2011 202 201 204 2I

Figure 15: Manufacturing outsourcing cost Index (AlIx Partners)

28

Furthermore, even if Chinese manufacturing costs reach U.S. levels by 2015, Axis Partners forecast that

production costs in Mexico and India will remain stable at 80 percent U.S. costs, making them still

attractive as offshoring destinations. Axis Partners report does not analyze manufacturing costs in even

lower wage countries like Vietnam, Indonesia and the Philippines, and even if they have not achieved

the scale, efficiency and supply chain yet, they are becoming popular offshoring destinations.

It is important to note that currency exchange rate, the most sensitive variable on Alix Partners model,

has been favoring U.S. international competitiveness in the last four years. The U.S. Dollar has

depreciated against the Mexican Peso and Chinese Renminbi by 10 percent since 2009 (see figure 16),

making U.S. labor more competitive in the international landscape. Nevertheless this devaluation, fueled

by an extraordinary low interest rate and three rounds of quantitative easing, it is not likely to continue

in the long term.

*USocNY -9,

eU SDMXN te7%

7

15%

10%

2010

2011

2012Z

Figure 16: USD/CNYMXN,INR exchange rates (Google Finance)

To exemplify this new reshoring interests, The Economist uses the example of General Electric, who will

hire 1,100 IT engineers for its Michigan office to be closer to their business user and to develop new

applications for customers more quickly. Nevertheless this decision of hiring local teams to work closely

with business users is by no means enough to sustain that General Electric is redefining their offshoring

strategy as they still develop half of their ITwork by outside providers, most of them located in India.

29

The Economist also uses the example of General Motors, who decided to reverse its rule of outsourcing

90 percent of its IT work, because "IT has become more pervasive in our business and we now consider

it a big source of competitive advantage". Nevertheless the decision of cancelling several of their

outsourcing contracts with Indian providers does not necessarily mean that those jobs are going to be

reshored. Indeed many companies are opening their own IT hubs in India, where they can get the

advantages of a proprietary technology division, an important technology ecosystem where they can

easily find skilled workers and the lower costs associated with a developing country.

Finally the economist uses a survey from Alix Partners, McKinsey and Hackett to show that companies

today are less willing to offshore manufacturing processes compared to three years ago (see figure 17).

Nevertheless this small change of only three percent together with the punctual reshoring actions may

also reflect an attempt to placate public opinion as the offshoring debate is hurting companies image.

Furthermore the percentage of companies willing to offshore their production is still higher than the

percentage of companies thinking about reshoring.

Companies' intentions to change manufacturing source, worldwide, %of capacity

2009-11

26%

2012-1'

1 6%

23%19%

9_/

6%

Movebeen

high-costcountries

#eshore

9%

Figure 17: Companies' Intentions to change manufacturing source (The Economist)

It is also interesting to note the significant increase of companies thinking about moving their

production between low-cost countries. As countries like Vietnam, Philippines or Indonesia start to

consolidate as offshoring destinations, we can expect an important shift due to even lower production

costs. This competition between low and lower-cost countries will be a interesting phenomenon to

follow in the next years.

30

Conclusion

Over the last years there has been a public debate about the possible effects of increased

offshoring practices on the U.S. economy and more specifically on the U.S. labor market. This public

debate motivated U.S. Congress to take action. On October 22, 2004 the Congress passed the "American

Jobs Creation Act of 2004" which contains a provision to encourage profit repatriation back to the U.S.

by domestic multinationals. Yet the evidence linking offshore activities with falling domestic demand is

still under dispute.

While most there is significant evidence that offshoring has provided substantial cost savings and

improved profits for companies engaging in this practices, it is still not clear how these benefits are

propagated into the broader economy. Many authors [Mitra, 20071, [Global Insight, 20041, assume that

these cost savings are mostly transformed into lower consumption prices, benefiting equally all

consumers and increasing their purchasing power. This theoretical increased purchasing power would

have a positive impact in employment if oriented towards demand for local goods and services.

Nevertheless a careful analysis of the increasing gap between inflation in the prices of goods consumed

by American households (CPI) relative to the price of goods produced by American workers (GDPD)

provides evidence against this theory (see figure 9). The fact that prices of products produced overseas

and consumed by American families are rising more sharply than the GDPD over the last three decades

is also consistent with the data about corporate sector profit growth (see figure 11) as corporate sector

profits grew three times faster than personal income.

If productivity gains are not transferred into final lower prices, U.S. workers become net losers in

offshoring practices as they see their wages decrease [Ebenstein, 2011]. In addition this decrease on

offshorable worker wages will also increase within-country income inequality. This prediction is aligned

with Stolper-Samuelson theorem "Trade increases the real return to the factor that is relatively

31

abundant in each country and lowers the real return to the other factor" [Samuelson, 1941]. This means

that in the U.S., with an abundance of skilled unoffshorable labor, wages of workers should increase

relative to unskilled and offshorable workers and inequality should rise with offshoring.

The issue of offshoring requires a careful response from policy makers as its potential benefits are not

being equitably distributed among firms and workers. Any policy response must therefore be well

informed about the costs and benefits of offshoring practice and a new social contract needs to be put

given to U.S. workers to ensure they take advantage of the benefits of offshoring.

Directions for Further Research

Off-shoring is a difficult and complex phenomenon. It produces many and widespread economic

impacts, with U.S. employment and workers' wages being among the most sensitive. One of the main

difficulties stems in measuring the extent of offshoring in the U.S. Yet No comprehensive data exist on

the number workers who have lost their jobs as a result of the movement of work outside the U.S. The

only regularly collected statistics on jobs lost due to offshoring come from the U.S. Bureau of Labor

Statistics series on extended mass layoffs. Nevertheless these statistics underestimate the number of

jobs lost to offshoring as they exclude small companies and only focus on large layoffs. In addition it is

difficult to quantify the benefits accrued to a company from the enhanced competitiveness due to

offshoring practices, and how they are distributed among the different parties involved: consumers,

shareholders, employees of the firm and retained earnings.

To gain more insight about how this enhanced competitiveness is distributed among consumers,

shareholders and employees it would be interesting to select an industry and compare a set of

companies that significantly rely on offshoring practices against a set that does not. If we can isolate the

productivity gains due to offshoring we can then find out how they are distributed; in the form of lower

32

product prices which benefits consumers, in the form of higher profits which benefits shareholders, or in

the form of higher wages which benefits employees.

Furthermore it would be interesting to analyze the drivers of this behavior to develop the appropriate

regulatory and policy responses. Corporate taxes will have a significant influence on companies' decision

of reinvesting abnormal profits obtained abroad, but there may also be other factors that will shape

companies' behavior like market growth, labor availability and wages among others.

33

Bibliography

Antras, Pol, Luis Garicano and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg. "Offshoring in a Knowledge Economy". National

Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, Jan 2005.

Alix Partners. "2011 U.S. Manufacturing-Outsourcing Index". Alix Partners Researches, Dec 2011.

Barba Navaretti, Giorgio, Giuseppe Bertola and Alessandro Sembenelli. "Offshoring and Immigrant

Employment - Firm-Level Theory and Evidence". Centro Studi Luca d'Agliano Development

Studies Working Paper No. 245, Mar 2008.

Bhagwati, Jagdish, Blinder, Alan S. "Offshoring of American Jobs: What Response from U.S. Economic

Policy?". The MIT Press, 2009.

Blinder, Alan S., Krueger, Alan B. "Alternative Measures of Offshorability: A Survey Approach" CEPS

Working Paper No. 190, Aug. 2009.

Borga, Maria. "Trends in Employment at U.S. Multinational Companies: Evidence from Firm-Level Data".

Brookings Trade Forum, 2005.

Brainard, Lael and David Riker. "U.S. Multinationals and Competition from Low Wage Countries".

National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, Mar. 1997.

Byrne, David, Brian Kovak and Ryan Michelis. "Offshoring and Price Measurement in the Semiconductor

Industry". Measurement Issues Arising from the Growth of Globalization, Nov. 2009.

Crino, Rosario. "Service Offshoring and White-Collar Employment". The Review of Economic Studies,

Volume 77, Jun. 2010.

Desai, Mehir, Fritz Foley and James Hines. "Foreign Direct Investment and Domestic Economic Activity".

Harvard Business School Working Paper, Nov. 2005.

34

Ebenstein, Avraham, Ann Harrison, Margaret McMillan, and Shannon Phillips. "Estimating the Impact of

Trade and Offshoring on American Workers". Journalists Resource RSS. The World Bank, Aug.

2011.

Ebenstein, Avraham, Ann Harrison, Margaret McMillan, and Shannon Phillips. "Why American Workers

are Getting Poorer? Estimating the Impact of Trade and Offshoring using the CPS". National

Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, Jun. 2009.

Feenstra, Robert C., "Offshoring in the Global Economy". Stockholm School of Economics, Sep. 2008.

Fontagne, Lionel. "Foreign Direct Investment and International Trade: Complements or Substitutes?".

OECD Science, Technology and Industry Working Papers, Mar. 1999.

GAO. "OFFSHORING - U.S. Semiconductor and Software Industries Increasingly Produce in China and

India". United States Government Accountability Office, Sept. 2006.

Global Insight. "The Impact of Offshore IT software and Services Outsourcing on the U.S. Economy and

the IT Industry". Report to the Information. Global Insights, Mar. 2004.

Grossman, Gene and Esteban Rossi-Hansberg. "Trading Tasks: A Simple Theory of Offshoring". American

Economic Review, 2008.

Harrison, Ann and Margaret McMillan. "Offshoring Jobs? Multinational and U.S. Manufacturing

Employment". Review of Economics and Statistics, Sep. 2007.

Houseman, Susan N., Christopher Kurz, and Paul A. Lengermann. "Offshoring and the State of American

Manufacturing". Upjohn Institute, Jun. 2010.

Klier, Thomas H., and James M. Rubesntein. "Imports of Intermediate Parts in the Auto Industry - A Case

Study". Measurement Issues Arising from the Growth of Globalization, Nov. 2009.

Kremer, Michael and Keith Maskin. "Globalization and Inequality," Weatherhead Center for

35

International Affairs, Harvard University, 2006.

Mankiw, Gregory, and Philip Swagel. "The Politics and Economics of Offshore Outsourcing". National

Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper, Jul. 2006.

McCarthy, Kevin. "The End of Cheap Energy". Old Research Report, Dec. 2006.

McKinsey Global Institute. "Offshoring: Is it a Win-Win Game?". McKinsey Publications, Aug. 2003.

Mitra, Devashish, and Priya Ranjan. "Offshoring and Unemployment". National Bureau of Economic

Research Working Paper, Jun. 2007.

Muendler, Marc-Andreas and Sascha 0. Becker, "Margins of Multinational Labor Substitution". UC San

Diego Working Paper, Apr. 2006.

Pasti, Stefan. "The End of the Era of Cheap Energy". The IPCR Critical Challenges Assessment 2011, Sep.

2011.

Samuelson, Paul A. "Where Ricardo and Mill rebut and confirm arguments of mainstream economists

against globalization". Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 18, No. 3, Summer 2004.

Samuelson, Paul A., Stolper, F. Wolfgang. "Protection and Real Wages". Review of Economic Studies,

1941.

36

Appendix I: Imports of Goods and Manufacturing Jobs - Correlation

Analysis

Correlation between Good Imports and Employment

17000

$2,200,000

16000

$2,000,000

14000

-

-

$1,800,000

13000

CL

E $1,600,000

12000

_

--

'$1,400,000

-

----

11000

-

-1--

-4 $1,200,000

-

Total Value of Imports of Goods

--

Manufacturing Jobs

9000

80oo

$1,000,000

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

Figure 18: Correlation analysis between imports of goods and manufacturing jobs

Table 1: Linear Regression Analysis for number of manufacturing mobs

18000

.4i

Unear Fit

Manufactuling Jobs = 20214.336 -0.0036545*Total Value of

Imports of Goods

17000-

J

16000 -

summary of Fit

15000-

RSquare

-RSquare

0.448242

Root Mean Square Error

Mean of Response

Observaticns (or Sum Wgts)

i

0t

1300012000 -ak

11000

1100000

0.498402

Adj

14000-

I

1300000

1500000

1700000

Total Value of

Impods of Goods

1900000

2100000

1368.323

14507.51

12

4AnalyssofVarance

Source

Model

Error

C. Total

OF

1

10

11

Squares Mean Square

18603806

18603806

18723090

1872309

37326896

Term

Intercept

Total Value of Imports of Goods

F Ratio

9.9363

Prob3-F

0.0103*

Esanate Std Error

20214.336 1853122

-0.003654 0.001159

t Rato Pro"pit

10.91 <.0001*

-315 0.0103*

37

Appendix II: Personal Income vs. Corporate Profit Growth Analysis

We can see how corporate profit growth was very much aligned to personal income growth between

1976 and 2000. Nevertheless since 2002, corporate profits grew at a much higher rate, increasing the

gap between wages and corporate profits.

Personal Income vs. Corporate Profit Growth

1400.00%

-

1200.00%

1000.00%

-

-

-

800.00%

-

Personal Income Growth Since

1976

-0.%

Corporate Profit Growth since

1976

-

400.00%

200.00%

0.00%

Figure 19: Capital gains vs. personal income since 1976 (Bureau of Economic Analysis)

To corroborate the reliability of this analysis we need to find if the correlation between personal income

and corporate profit is significant. For that purpose I have analyzed the correlation analysis between

corporate profit and personal income growth. As wages are stickier than corporate profits I have

introduced time delays.

0 years delay

1 year delay

2 years delay

3 years delay

0.019

0.418

0.227

0.090

As we can see the highest correlation appears when we compare corporate profit growth with personal

income growth of the next year.

38

Personal Income vs. Corporate Profit Growth

40.00%

30.00%

20.00%

-5 10.00%

-Personal

Income Growth

0.

U.LAJW

Corporate Profit Growth

0

r-J

-10.00%

-20.00%

-30.00%

Figure 20: Personal Income vs. corporate profit growth over time (Bureau of Economic Analysis)

A simple linear regression shows that there is a statistically significant correlation between the two

variables.

15.00%

d: Linear Fit

-

Personal Income Growth = 0.0554633 + 0.1011947*Corporate

Profit Growth

10.00%-

,a Summary of Fit

RSquare

RSquare Adj

Root Mean Square Error

0

5.00%-

(L

Mean of Response

Observatons (or Sum Wgts)

C

0.00%-

it

Analysis of Variance

Source

-5.00%-20.0%

30.0%

0.0%10.0%

Growth

Profit

Corporate

0.175067

0.150804

0.0302

0.063728

36

Model

Error

C. Total

SUm of

DF

Squares Mean Square

0.006581

1 0.00658092

0.000912

34 0.03101001

35 0.03759093

FRatio

7.2155

Prob F

0.0111*

a, Parameter Estmates

Term

Intercept

Corporate Profit Growth

Estimate

Std Error

0.055433

0.1011947

0.005899

0.037673

t Ratio Prob>lti

9.40

2.69

<.0001*

0.0111*

39