A STUDY OF PLANNING CENSUS

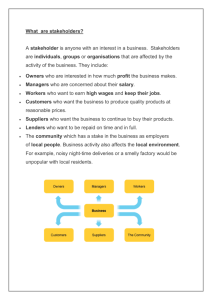

advertisement