I V

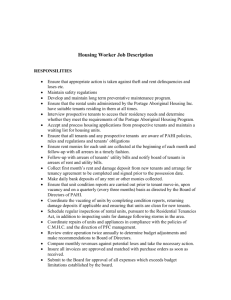

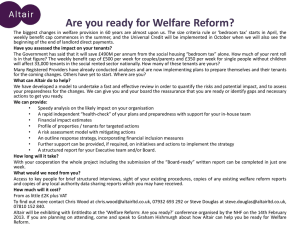

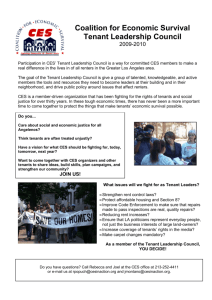

advertisement