Are we homogenising risk factors for public health

advertisement

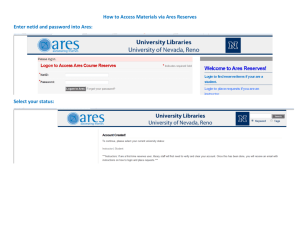

Downloaded from injuryprevention.bmj.com on August 23, 2011 - Published by group.bmj.com IP Online First, published on March 24, 2011 as 10.1136/ip.2010.030866 Original article Are we homogenising risk factors for public health surveillance? Variability in severe injuries on First Nations reserves in British Columbia, 2001e5 Nathaniel Bell,1 Nadine Schuurman,2 S Morad Hameed,3 Nadine Caron3,4 1 Department of Surgery, University of British Columbia, Trauma Services, Vancouver General Hospital, Vancouver, Canada 2 Department of Geography, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada 3 Department of Surgery, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada 4 Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland, USA Correspondence to Dr Nathaniel Bell, Department of Surgery, University of British Columbia, Trauma Services, Vancouver General Hospital, 855W. 12th Avenue, Vancouver, BC V5Z 1M9, Canada; nathaniel.bell@vch.ca Accepted 28 February 2011 ABSTRACT Background Aboriginal Canadians are considered to be at increased risk of injury. The de facto standard for measuring injury risk factors among Aboriginal Canadians is to compare hospitalisation and mortality against non-Aboriginal Canadians, but this may be too broad an approach for injury prevention and public health if it over-generalises injury risk. Methods Data from this study are drawn from the 2001e5 British Columbia Trauma Registry and British Columbia Coroner’s Service. Observed and expected hospitalisations and mortality rates on reserves were assessed against three different spatial aggregations of non-reserve reference populations. Data analysis was conducted in a geographical information system using a Poisson probability map. Results A total of 47 (9.6%) of 487 reserves in British Columbia contained at least one person who was hospitalised or died as a result of serious injury during the study period. Of these, two reserve populations represented 20% (n¼19) of all injury morbidity events and 30% (n¼22) of all mortality events. Conclusion Evidence from this study suggests that community-based rather than provincial-based injury reporting is less likely to over-generalise the burden of injury among Aboriginal communities. Community-based surveillance enables researchers to identify why severe unintentional and intentional injury continues to burden some communities but not others and avoids the potentially demoralising and stigmatising effects of current surveillance practices. Across Canada, First Nations peoples have been shown to experience disproportionately poorer health outcomes than non-Aboriginal Canadians, including an increased risk of ischaemic heart disease,1 diabetes2 3 and many cancers.4e6 Literature on disparities in risk is emerging in injury morbidity and mortality reports. Thus far, research has shown that First Nations peoples are nearly five times as likely to experience a major trauma than non-Aboriginal populations,7 over 11 times more likely to experience an assault that leads to extended hospitalisation,8 five times more likely to be hospitalised as a result of motor vehicle injury8 and over nine times more likely to die as a result of a severe burn injury.9 Suicide rates, which are the most commonly researched of all injuries among Aboriginal groups, have been shown to exceed 800 times the national average among some Aboriginal communities,10 with Aboriginal Canadians nearly four times less likely than non-Aboriginal Canadians to have sought previous psychiatric care.11 BellCopyright N, Schuurman N, Hameed author SM, et al. Injury Prevention (2011). doi:10.1136/ip.2010.030866 Article (or their employer) 2011. Produced The de facto standard for quantifying health disparities among Aboriginal groups has been to draw comparisons of health outcomes between Aboriginal Canadians and non-Aboriginal Canadians. Social scientists have challenged that this approach is too broad as it has a demoralising and stigmatising effect on members of the community.10 12 13 One such study in Canada found that the heterogeneity in suicide rates among British Columbia’s First Nations peoples make it impossible to generalise risk factors at the provincial scale.10 However, this evidence is largely based on case studies from a subset of the population. Expanding on these initial findings may potentially improve how we conceptualise health disparities and could guide social, medical and political solutions for each specific community.14 The purpose of this study is to assess the magnitude of injury morbidity and mortality on First Nations reserves, examine if incidence rates on reserves are significantly higher or lower than among non-reserve areas, and determine if health disparities indicators for injury surveillance efforts are best directed at the local, regional, or provincial scale. Our analysis is conducted using provincewide administrative health data on major trauma injury and mortality from British Columbia, which has the largest concentration of Aboriginal lands in Canada. METHODS Severe injury hospitalisations and deaths among populations aged over 17years were analysed using individual case records from the British Columbia Trauma Registry (BCTR) and British Columbia Coroner’s Service (BCCS) database inclusive of 1 January 2001 to 31 December 2005. In January 2006, there were nine adult level IeIV trauma hospitals in British Columbia. All patients requiring a trauma team consultation or a trauma team activation at one of the province’s level IeIV trauma centres are recorded in the BCTR. For this study, cases from both the BCTR and the BCCS database were stratified by injury mechanism into unintentional, intentional self-harm, and intentional third-party categories. In British Columbia, all injury inclusion criteria for the trauma registries are derived using the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision. The BCCS uses its own inclusion criteria when defining the mechanism of death. All case records were extracted by one author (NB) familiar with the coding scheme of both the BCTR and BCCS. All in-facility deaths were counted within the BCCS records. 1 of 7 by BMJ Publishing Group Ltd under licence. Downloaded from injuryprevention.bmj.com on August 23, 2011 - Published by group.bmj.com Original article Figure 1 Poisson probability map construction. The probability map is constructed by using the spatial adjacency functions in geographical information systems (GIS) to identify all areas that share a boundary with each reserve. Denominators for crude hospitalisation and mortality rates on and off reserves were constructed from the 2001 census subdivision (CSD) population counts. CSD are roughly equivalent in size to a municipality or large urban city. Each Aboriginal reserve has a federally designated administrative boundary that is assigned a unique CSD ID. Reserve boundaries are self-contained geographies and are contiguous with non-reserve administrative boundaries used by Statistics Canada. Trauma and coroner records were linked to the CSD boundaries using the patient/ person’s postal code of residence as recorded in the BCTR and BCCS. We used the single link indicator flags within the March 2006 postal code conversion file to assign rural postal codes that fell within multiple CSD into a single administrative unit. While place of residence may not reflect place of injury, previous studies have found that 96% of unintentional injuries took place in the census tract of the individual’s residence.15 Comparisons between injury morbidity and mortality rates on and off reserves were analysed in a geographical information system (GIS) using a probability mapping model.16 Probability maps are similar to standard mortality ratios in that they contrast observed events to expected events in a population, but differ in that the output is the statistical significance of the incidence rates rather than the rates themselves. In probability mapping, statistical significance of a health event, i, is measured by the probability that shows the likelihood of a rate occurring given the normal rate of an event within the reference population, p. The probability value for each area represents the likelihood that the rate observed in that area would occur by chance if the underlying risk of injury was equal to p.17 For this study we used the Poisson probability test. This is appropriate for the study of injuries, as injuries, like many diseases, occur within only a small fraction of the population and are either present or absent. We used topological functions of GIS to build three different scenarios to express the likelihood that the injuries occurring on reserves were significantly higher or lower relative to non-reserve reference populations. We constructed a discrete probability map from the Poisson distribution: x P x ¼ el l =x! where l is the product of the reserve population count multiplied by the reference area rate. At the smallest geographical scale, expected reference area rates were constructed from the non-reserve CSD that were adjacent to each reserve: 2 of 7 k1 P x$k ¼ 1 + PðxÞ x¼0 where k is the number of trauma injuries occurring among populations living on a reserve and P(x) is the probability that the number of cases would occur by chance if the reserve had a similar population distribution as the surrounding reference population(s). Only comparisons with p values of 0.05 or less are flagged as significant. Regional comparisons were also assessed using the health service delivery areas (HSDA) (n¼16) as these are the administrative areas used by the provincial health authorities for resource allocation and disease surveillance. The regional comparisons were based on the summation of all reserve injuries that fell within each HSDA against all nonreserve injury rates within the HSDA. The provincial comparison was based on the summation of all reserve injuries against the number of non-reserve injuries for the entire province. Figure 1 illustrates the process steps for constructing a probability map in a GIS. RESULTS During the study period, a total of 93 persons who were hospitalised due to a severe injury were identified as living on a reserve up to the time of their injury. A total of 73 persons who died while in hospital, while in transit, or at the scene as a result of their injury were identified as living on a reserve up to the time of their injury. Counts of non-reserve injury hospitalisations and deaths at the provincial scale are shown in table 1. All cases with missing residential address information or with a residential address that was out of province were excluded from the analysis. This resulted in the exclusion of 647 records from the BCTR and 4689 records from the BCCS. Table 1 On and off-reserve injury morbidity and mortality counts from the BCTR and BCCS for calendar years 2001e5 Data description Registered (2001e5) Valid postal code for person’s place of residence Occurring off a reserve Occurring on a reserve Hospitalisations (BCTR) Count Deaths (BCCS) Count 6124 5811 8811 4122 5718 93 4049 73 BCCS, British Columbia Coroner’s Service; BCTR, British Columbia Trauma Registry. Bell N, Schuurman N, Hameed SM, et al. Injury Prevention (2011). doi:10.1136/ip.2010.030866 Downloaded from injuryprevention.bmj.com on August 23, 2011 - Published by group.bmj.com Original article Table 2 Injury and mortality rate for British Columbia (crude incidence rates, 2001e5), on and off reserves Severe injury morbidity and mortality on and off reserve for British Columbia, 2001e5 Hospitalisations Scale Province On-reserve Off-reserve Deaths Intentional self-harm Unintentional Intentional third party Unintentional Intentional self-harm Intentional third party Count Rate Count Rate Count Rate Count Rate Count Rate Count Rate 83 5062 622.2* 322.1 1 130 7.5 8.3 9 526 67.5* 32.4 48 2759 368.1* 240.4 22 1121 168.7* 97.7 3 169 23.0 14.7 Rates are per 100 000. *Rate significantly higher than non-reserve rate (p#0.05). The 166 on-reserve injury morbidity and mortality cases represented 1.7% of all cases in the analysis, which was proportionate to the on-reserve population as a whole, with an estimated 1.7% (n¼68 235) of the province’s 3 907 738 persons residing on a reserve in 2001.18 A total of 47 of the province’s 487 reserves recorded at least one person who was injured or died as a result of serious injury during the study period. Of these, 20% (n¼19) of all injury morbidity events and 30% (n¼22) of all mortality events occurred to persons who resided in areas 27 and 29. Tables 2e4 illustrate the on and off-reserve injury morbidity Table 3 and mortality count and crude rates at the provincial, regional and municipal scale. The ratio between observed and expected counts of injury hospitalisations and deaths by reserves at the HSDA scale are shown in figure 2. To protect confidentiality the injury locations by reserve are not shown. At the provincial scale, incidence rates of injury on reserves were statistically higher than non-reserve areas in four of the six classes of injuries analysed in this study. A total of 11 of the 16 HSDA contained at least one reserve where someone required hospitalisation or died as a result of a severe injury during the Injury and mortality rate by HSDA (crude incidence rates, 2001e5), on and off reserves Severe injury morbidity and mortality on and off reserve by HSDA, 2001e5 Hospitalisations Scale HSDA 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve On-reserve Off-reserve Deaths Unintentional Intentional self-harm Intentional third party Count Rate Count Rate Count e 12 e 98 19 419 15 415 3 240 e 614 2 635 e 111 4 864 14 415 9 602 7 224 2 115 7 83 1 162 e 35 e 262.9 e 430.9 436.8* 330.4 1515.2* 492.1 2000* 276.9 e 267.2 2105.3* 278.1 e 209.0 416.7 310.8 804.6* 433.6 286.2 374.2 880.5* 281.6 526.3 321.7 1166.7* 290.2 740.7 399.8 e 248.4 e 0 e 0 e 8 e 6 e 5 e 20 e 15 e 0 e 37 e 6 e 18 e 7 e 2 1 2 e 3 e 1 e 0.0 e 0.0 e 6.3 e 7.1 e 5.8 e 8.7 e 6.6 e 0.0 e 13.3 e 6.3 e 11.2 e 8.8 e 5.6 166.7* 7.0 e 7.4 e 7.1 e 0 e 4 1 21 2 41 e 20 e 86 e 84 e 12 e 135 2 25 1 51 1 14 1 7 e 8 1 18 e 0 Unintentional Intentional self-harm Rate Count Rate Count e 0.0 e 17.6 23.0 16.6 202.0 48.6 e 23.1 e 37.4 e 36.8 e 22.6 e 48.6 114.9 26.1 31.8 31.7 125.8 17.6 263.2 19.6 e 28.0 740.7 44.4 e 0.0 e 116 e 153 21 374 12 334 e 75 e 101 e 160 e 62 1 523 2 173 3 212 3 182 1 85 4 56 1 92 e 49 e 366.6 e 442.4 391.4* 283.2 1039.0* 425.1 e 168.3 e 154.3 e 152.2 e 141.3 357.1 230.3 101.0 233.2 152.3 202.9 327.9 203.0 512.8 200.8 382.8 251.8 740.7 280.8 e 298.7 41.0 45.0 4 146 4 112 e 12 e 48 e 52 e 34 2 263 3 92 1 96 6 94 e 34 2 21 e 19 e 7 Intentional third party Rate Count Rate e 129.6 e 130.1 74.6 110.6 346.3 142.6 e 26.9 e 73.3 e 49.5 e 77.5 714.3 115.8 151.5* 124.0 50.8 91.9 655.7* 104.8 e 80.3 191.4 94.4 e 58.0 e 42.7 e 1 e 7 e 15 1 12 e 4 e 15 e 20 e 4 e 44 1 9 1 8 e 9 e 3 e 3 e 11 e 3 e 3.2 e 20.2 e 11.4 86.6 15.3 e 9.0 e 22.9 e 19.0 e 9.1 e 19.4 50.5 12.1 50.8 7.7 e 10.0 e 7.1 e 13.5 e 33.6 e 18.3 Rates are per 100 000. Eighteen cases from the British Columbia Trauma Registry were excluded due to overlap between census subdivision (CSD) and multiple health service delivery area (HSDA) geographical areas. Eighteen cases from the British Columbia Coroner’s Service were excluded due to overlap between CSD and multiple HSDA geographical areas. *Rate significantly higher than non-reserve rate (p#0.05). Bell N, Schuurman N, Hameed SM, et al. Injury Prevention (2011). doi:10.1136/ip.2010.030866 3 of 7 Downloaded from injuryprevention.bmj.com on August 23, 2011 - Published by group.bmj.com Original article Table 4 Injury and mortality rate by CSD (crude incidence rates, 2001e5), on and off reserves Severe injury morbidity and mortality on and off reserve by CSD, 2001e5 Hospitalisations Scale CSD Area 1 Area 2 Area 3 Area 4 Area 5 Area 6 Area 7 Area 8 Area 9 Area 10 Area 11 Area 12 Area 13 Area 14 Area 15 Area 16 Area 17 Area 18 Area 19 Area 20 Area 21 Area 22 Area 23 Area 24 Area 25 Area 26 Area 27 Area 28 Area 29 Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) Deaths Unintentional Intentional self-harm Count Rate Count Rate Count Rate Count Rate Count Rate Count Rate 2 35 1 e 1 71 1 72 1 145 2 408 4 983 e e 3 1112 7 1112 1 79 1 226 3 229 1 457 3 457 1 34 e e 2 80 1 65 3 e e 30 1 39 1 42 e e 1 15 2 2 6 182 3 229 12 255 NA 238.5 2000 e 1538.5 257.71 2857.1 260.12 2000 266.03 2105.3* 274.16 416.67 295.82 e e 1176.5* 316.48 522.39 316.48 666.67 516 86.207 337.29 845.07 366.99 NA 356.66 202.7 356.66 1666.7 286.8 e e 714.29 330.03 666.67 242.18 983.6 e e 213.6 512.82 266.58 769.23 247.86 e e 909.09 337.46 2352.9* 314.96 1935.5* 423.16 322.6 363.46 368.1 355.85 e e e e e 1 e 1 e 3 e 10 e 37 e e e 43 e 43 e e e 8 e 8 e 17 e 17 e e e e e e e 3.63 e 3.61 e 5.5 e 6.72 e 11.1 e e e 12.2 e 12.2 e e e 11.9 e 12.8 e 13.3 e 13.3 e e e e e 12.4 e 11.2 e e e e e 13.7 e 11.8 e e e e e e e 6.98 e 9.52 e 9.77 e e e e e 5 e 5 e 13 e 68 e 147 e e e 151 e 151 e 2 1 10 e 12 e 49 e 49 e 3 e e e 4 e 5 1 e 1 1 e 1 e 1 e e e 3 e e e 18 e 13 1 14 e e e e e 18.15 e 18.06 e 23.85 e 45.69 e 44.24 e e e 42.98 e 42.98 e 13.06 86.2 14.92 e 19.23 e 38.24 e 38.24 e 25.31 e e e 16.5 e 18.63 327.9 e 1818.2* 7.12 e 6.835 e 5.901 e e e 67.49 e e e 41.85 e 20.63 30.7 19.54 1 70 NA 287.5 e e e e e e e e e e 357.1 215.8 106.4 208.3 e 210.9 127.4 216.2 0 238.2 0 238.9 281.7 238 e e 200 182.9 e e e 206.8 845.1* 230.7 e 189 e e e e 512.8 182.2 e e 952.4* e 571.4 411.1 e e 1062* 311.5 388.3 247.3 312.5 257.1 1 39 NA 160.2 e e e e e e e e e e 714* 110 e 110 392 113 255 115 e 83.5 215 80.5 e 85.3 e e e 85.4 e e 952 86.2 563* 95.8 667 101 656 e e e e 67.7 e e 1905* 157 e 123 e e 354 123 e 100 56.8 100 e 2 e e e e e e e e e e e 48 e 61 e 55 1 49 1 2 e 2 e 2 e e e 7 e e e 1 e 1 e 4 e e e e e e e e e e e e e e 1 5 e 7 e 8 e 8.2 e e e e e e e e e e e 17.6 e 19.8 e 18 127.4 17.6 666.7* 4.07 e 5.03 e 4.49 e e e 8.42 e e e 5.74 e 4.35 e 10.6 e e e e e e e e e e e e e e 177 12.8 e 11.3 e 12.2 e e 3 e 3 e e e e e 2 e 2 e e e e e e e 3 e 6 e 7 Intentional third party Unintentional Intentional self-harm e e e e e 1 588 1 641 0 645 1 602 0 117 0 95 1 106 e e 2 152 e e e 36 3 53 e 71 e e e e 1 35 e e 1 e 1 20 e e 6 122 4 153 11 169 e e e e e 2 300 e 339 1 346 2 320 e 41 1 32 e 38 e e e 71 e e 1 15 2 22 1 38 2 e e e e 13 e e 2 1 e 6 e e 2 48 e 62 2 66 Intentional third party Continued 4 of 7 Bell N, Schuurman N, Hameed SM, et al. Injury Prevention (2011). doi:10.1136/ip.2010.030866 Downloaded from injuryprevention.bmj.com on August 23, 2011 - Published by group.bmj.com Original article Table 4 Continued Severe injury morbidity and mortality on and off reserve by CSD, 2001e5 Hospitalisations Scale CSD Area 30 Area 31 Area 32 Area 33 Area 34 Area 35 Area 36 Area 37 Area 38 Area 39 Area 40 Area 41 Area 42 Area 43 Area 44 Area 45 Area 46 Area 47 Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent Reserve Adjacent area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) area(s) Deaths Unintentional Intentional self-harm Intentional third party Unintentional Intentional self-harm Intentional third party Count Rate Count Rate Count Rate Count Rate Count Rate Count Rate e e 2 66 e e 2 5 2 5 1 3 0 3 e e 4 e 3 3 e e e e 1 e e e 2 16 1 e e e 1 1 e e 1250* 235.59 e e 833.3 757.58 3333.3 757.58 6666.7 2400 0.0 2400 e e 2758.6 e 833.33 431.65 e e e e 666.67 e e e 2222.2 1019.1 NA e e e 740.74 454.55 e e e 1 e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e 1 e e e e e e 3.57 e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e NA e e e e e e 5 e e e e e e e e 2 e e e 2 e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e 1 e e e e 17.85 e e e e e e e e 1666.7* e e e 1379 e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e 740.7* e 1 157 4 86 1 51 e e e e 1 6 1 6 1 1 e e 1 4 e e 1 e e 11 1 6 e e e e e e 1 2 152.7 252.8 2500* 219.6 3333 354.2 e e e e 6667 4800 833.3y 4800 689.7 1250 e e 277.8 350.9 e e 425.5 e e 188 487.8 170.9 e e e e e e 740.7 481.9 e 62 1 30 e 16 e e e e e 2 e 2 e e e e e 1 1 e e e 1 1 e 2 e e e e e e e e e 99.8 625 76.6 e 111 e e e e e 1600 e 1600 e e e e e 87.7 1053 e e e 667* 17.1 e 57 e e e e e e e e e 7 e 3 e 3 e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e 1 e e e e e e e e e 11.3 e 7.66 e 20.8 e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e e 28.5 e e e e e e e e Rates are per 100 000. NA, reserve population has a base population count of zero. The primary reason for a base population count of zero is that the area is a non-residential reserve (eg, land used for resource purposes only). In some cases, Statistics Canada may choose to suppress the population counts for all areas with fewer than 40 people. *Rate significantly higher than spatially adjacent non-reserve rate (p#0.05). yRate significantly lower than spatially adjacent non-reserve rate (p#0.05). CSD, census subdivision. study period. The number of intentional and unintentional injury hospitalisations and deaths on reserves were significantly higher than the number of injuries among non-reserve populations in seven of the 11 HSDA. When analysed at the municipal scale (ie, CSD), incidence rates of unintentional and intentional injury morbidity and mortality were significantly higher than rates within spatial adjacent non-reserve communities within 12 of the 47 reserves, with the rate of injury mortality within one reserve significantly lower than the adjacent non-reserve municipalities. DISCUSSION Albeit with few exceptions,10 13 public health surveillance of Aboriginal Canadian health outcomes largely fails to demonstrate whether reported health events are representative of the majority of the population included in the analysis. This study demonstrated that injuries on reserves are far more concentrated than widespread. Fewer than 10% of all reserves in BC were represented in either the BCTR or BCCS database, with 25% (n¼41) of all hospitalizations and deaths occurring among populations residing on two reserves. Fewer than 30% of all reserves (n¼12) exhibited significantly higher incidence rates than the neighbouring non-reserve areas. These results suggest that the burden of injury among Aboriginal communities in BC is not unlike the burden of injury among non-Aboriginal communities. As such, the results from this study are potentially significant as the evidence suggests that there is no universal health indicator for measuring injury outcomes on reserves. This is not surprising when one considers the profound legal, cultural, geographical and political circumstances that distinguish First Nations groups from all other population groups in Canada. For example, in British Columbia, there are over 200 First Nations communities and nearly 500 reserve lands set aside for the exclusive use of status ‘Indians’. First Nations peoples in British Columbia practise both Bell N, Schuurman N, Hameed SM, et al. Injury Prevention (2011). doi:10.1136/ip.2010.030866 5 of 7 Downloaded from injuryprevention.bmj.com on August 23, 2011 - Published by group.bmj.com Original article Figure 2 Ratio of observed/expected unintentional injury hospitalisations and deaths on reserves, British Columbia, Canada, by regional health service delivery area, 2001e5. Christian and indigenous religious traditions, speak over 40 languages, and reside across the full spectrum of the province’s urban, rural and remote areas. The geographical location of the reserves is so diverse that Indian and Northern Affairs Canada must consider the location, distance from major population centres, and the local climatic conditions when allocating federal funding to First Nations communities.19 In the USA, these complexities have challenged how healthcare providers understand major health issues among Aboriginal populations as there is no model community or experience that can accurately serve as a baseline population that reflects the diversity of what would otherwise seem to be a tiny subpopulation of the country’s landscape.20 A similar perspective is needed in Canada when strategising for public health surveillance and prevention. No study that employs administrative data to measure geographical variations of injury is free from error. One of the limitations of this study is that we probably underestimate the burden of injury among Aboriginal communities because of the inability to assess ‘status Aboriginal’ from the BCTR or BCCS patient population. Unlike other provinces, there is no memorandum of understanding between the provincial health authorities and First Nations populations to enable trauma registry data coders to identify whether the injured patient is First Nations. This is a significant challenge to injury prevention research in British Columbia as approximately 60% of all First Nations live off reserves.21 Although the methods used in this study do present a strong effort to circumvent gaps in current data availability, this limitation should be considered when interpreting the data. A second limitation is due partly to the increasing weight being given to injury rates on a reserve-by-reserve basis when in fact the population and event counts in the majority of these 6 of 7 areas are small. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention takes the position that ‘when the total number of deaths used to calculate any rate (crude, age-adjusted, or smoothed) is 20 or less, the rate is considered statistically unstable’.22 In defence of small area analysis, the occurrence of injury cases must be related to the population at risk of succumbing to injury. As Aboriginal communities are typically small in numbers, data suppression is rarely, if ever, practical. In this event, the strength of the Poisson test is well suited for finding out whether the actual number of cases within a small study or sample area is unusual as the comparisons are made in reference to an expected national or regional prevalence rate. The fact that the injury events in this study were derived from a total of 47 of the province’s 487 reserves should further illustrate the concentration of injury in British Columbia and the necessity of small area analysis for injury prevention and control. Furthermore, this study is limited by the use of administrative data (eg, postal codes, census data) to derive population counts on reserves. Although on-reserve population counts are widely known to experience respondent error and other count inaccuracies, the notable benefit of using census data is that comparable data from non-reserve populations are also readily available from the same data source. A more troublesome limitation is gaps in geographical coding of BCCS and BCTR at the postal code level, which could be improved upon through either the use of geographical positioning systems or mandating more detailed patient information collection by first responders. Public health surveillance of Aboriginal people in Canada is complex, involving multijurisdictional coordination, but with increasingly greater control by Aboriginal communities in delivering and regulating culturally relevant health and wellness Bell N, Schuurman N, Hameed SM, et al. Injury Prevention (2011). doi:10.1136/ip.2010.030866 Downloaded from injuryprevention.bmj.com on August 23, 2011 - Published by group.bmj.com Original article What is already known on this subject < Trauma continues to be a significant health issue for Aboriginal and indigenous populations in Canada and across the globe. < Morbidity and mortality rates of injury are disproportionately higher among Aboriginal and indigenous populations compared with non-Aboriginal and non-indigenous populations. < Although the literature is limited, Aboriginal and indigenous populations are frequently referenced in academic and governmental documents as a particular ‘at-risk’ or ‘vulnerable’ population to injury and other diseases. inclusion of GIS for injury prevention and control is still emerging. Despite its ability to circumvent many of the limitations in current data availability through employing spatial and non-spatial data linkages, stronger multidisciplinary approaches are needed to ensure that these tools become standard practice for injury prevention and control. Acknowledgements The authors wish to thank the British Columbia Trauma Registry and the British Columbia Coroner Service for access to these data. The authors also wish to thank Dr Ian Pike from the BC Injury Research & Prevention Unit and three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions. Funding Funding for this research was provided by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research (IN-RUS-0186). Funding for N Bell is provided by a fellowship awarded by the Canadian Institute for Health Research. Competing interests None. Ethics approval This study was conducted with the approval of the University of British Columbia. What this study adds < Incidence patterns of injury morbidity and mortality on First Nations lands in British Columbia, Canada, are far more concentrated than widespread. Populations who resided in two of the province’s 487 reserves represented 25% of all on-reserve injury mortality and morbidity. < Results from this study support ongoing discourse that characterising Aboriginal health outcomes to non-Aboriginal health outcomes is too broad an approach for injury prevention and public health. < This study emphasises the spatial and non-spatial data linkage tools and spatial analysis capabilities of GIS for injury prevention and control and outlines a methodology for its use in small-area analysis. Contributors All authors have contributed to the drafting, conception, and writing of this manuscript. All analyses were conducted by NB. Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed. REFERENCES 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 23 24 initiatives. In addition, system-wide surveillance of injury demography is still needed as all injured populations are mandated to have access to definitive medical care irrespective of acuity.25 As part of this commitment, an inclusive trauma system not only coordinates injury control efforts across defined geographical areas, but also engages in research, training and performance improvement to gain a better understanding of the value of trauma systems, the key criteria needed to ensure optimal patient outcomes, and the epidemiology and pathophysiology of injury.25 This requires timely analysis, interpretation and dissemination of data on health-related events to both protect and promote health and prevent injury. The findings and limitations highlighted in this study should support modifications of trauma data collection to benefit future public health efforts. The inclusion of GIS in public health practice has increased significantly over the past decade with the recognition that health surveillance practices need to become more sensitive to the needs of people in local geographical areas.26 This study benefited from the data linkage and spatial analysis tools of GIS, which we used to ‘zoom in’ and explore statistical relationships between reserves and adjacent non-reserve areas across three geographical scales using a Poisson probability model. Injury rates on and off reserves were analysed in the GIS using provincially defined administrative boundaries and, as such, represent the primary data sources currently available for monitoring injury trends. These methodologies can be combined within ongoing efforts to understand the context in which injuries occurdfrom global to localdand gain valuable insight as to why some communities are healthier than others. The 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. Bell N, Schuurman N, Hameed SM, et al. Injury Prevention (2011). doi:10.1136/ip.2010.030866 Shah BR, Hux JE, Zinman B, et al. Increasing rates of ischemic heart disease in the native population of Ontario, Canada. Arch Intern Med 2000;160:1862e6. Panagiotopoulos C, Rozmus J, Gagnon RE, et al. Diabetes screening of children in a remote First Nations community on the west coast of Canada: challenges and solutions. Rural Remote Health 2007;7:771. Oster RT, Toth EL, Oster RT, et al. Differences in the prevalence of diabetes risk-factors among First Nation, Metis and non-Aboriginal adults attending screening clinics in rural Alberta, Canada. Rural Remote Health 2009;9:1170. Rosenberg T, Martel S, Rosenberg T, et al. Cancer trends from 1972e1991 for registered Indians living on Manitoba reserves. Int J Circumpolar Health 1998;57(Suppl 1):391e8. Marrett LD, Chaudhry M, Marrett LD, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality in Ontario First Nations, 1968e1991 (Canada). Cancer Causes Control 2003;14:259e68. MacMillan HL, MacMillan AB, Offord DR, et al. Aboriginal health. Can Med Assoc J 1996;155:1569e78. Harrop AR, Brant RF, Ghali WA, et al. Injury mortality rates in native and non-native children: a population-based study. Public Health Rep 2007;122:339e46. Karmali S, Laupland K, Harrop AR, et al. Epidemiology of severe trauma among status Aboriginal Canadians: a population-based study. Can Med Assoc J 2005;172:1007e11. Gilbert M, Dawar M, Armour R. Fire-related deaths among Aboriginal people in British Columbia, 1991e2001. Can J Public Health 2006;97:300e4. Chandler MJ, Lalonde CE. Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide in Canada’s first nations. Transcult Psychiatry 1998;35:191e219. Malchy B, Enns MW, Young TK, et al. Suicide among Manitoba’s Aboriginal people, 1988 to 1994. Can Med Assoc J 1997;156:1133e8. Kirmayer L. Suicide among Canadian Aboriginal peoples. Transcult Psychiatr Res Rev 1994;31:3e57. Auer AM, Andersson R. Canadian Aboriginal communities: a framework for injury surveillance. Health Promot Int 2001;16:169e77. Caron NR. Getting to the root of trauma in Canada’s Aboriginal population. Can Med Assoc J 2005;172:1023e4. Joly MF, Foggin PM, Pless IB. Geographical and socioecological variations of traffic accidents among children. Soc Sci Med 1991;33:765e9. Choynowski M. Maps based on probabilities. J Am Stat Assoc 1959;54:385e8. Cromley E, McLafferty S. GIS and public health. New York: The Guilford Press, 2002. BC Ministry of Health. 2001 Census fast facts: BC Indian Reserves. Victoria: Ministry of Management Services, 2001. Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. Band classification manual. Ottawa: INAC, 2005. Gone JP. Mental health services for Native Americans in the 21st century United States. Prof Psychol Res Pract 2004;35:10e18. Statistics Canada. 2001 Census. Aboriginal peoples of Canada: a demographic profile. Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2003. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suppression of unstable rates. 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/mapping_help/unstable_rates_3_4.html (accessed 30 Dec 2010). Newbold KB. Problems in search of solutions: health and Canadian Aboriginals. J Community Health 1998;23:59e73. Ladner KL. Understanding the impact of self-determination on communities in crisis. J Aboriginal Health 2009;Nov:88e101. Trauma Association of Canada. Trauma system accreditation guidelines. Calgary, AB: TAC, 2007. Gatrell AC, Loytonen M. GIS and health research: an introduction. In: Gatrell AC, Loytonen M, eds. GIS and health. London: Taylor and Francis, 1998. 7 of 7 Downloaded from injuryprevention.bmj.com on August 23, 2011 - Published by group.bmj.com Are we homogenising risk factors for public health surveillance? Variability in severe injuries on First Nations reserves in British Columbia, 2001 −5 Nathaniel Bell, Nadine Schuurman, S Morad Hameed, et al. Inj Prev published online March 24, 2011 doi: 10.1136/ip.2010.030866 Updated information and services can be found at: http://injuryprevention.bmj.com/content/early/2011/03/24/ip.2010.030866.full.html These include: References This article cites 19 articles, 7 of which can be accessed free at: http://injuryprevention.bmj.com/content/early/2011/03/24/ip.2010.030866.full.html#ref-list-1 P<P Email alerting service Published online March 24, 2011 in advance of the print journal. Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article. Sign up in the box at the top right corner of the online article. Notes Advance online articles have been peer reviewed, accepted for publication, edited and typeset, but have not not yet appeared in the paper journal. Advance online articles are citable and establish publication priority; they are indexed by PubMed from initial publication. Citations to Advance online articles must include the digital object identifier (DOIs) and date of initial publication. To request permissions go to: http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions To order reprints go to: http://journals.bmj.com/cgi/reprintform To subscribe to BMJ go to: http://group.bmj.com/subscribe/