by MASSACHUSETTS 1979 B.S., Columbus College

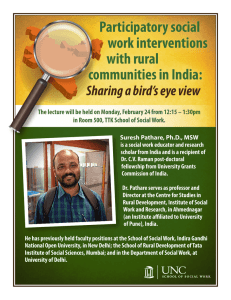

advertisement