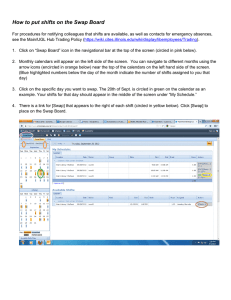

Swap Meets, Flea Markets, and ...

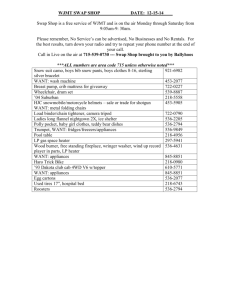

advertisement