JUN 10 1965 .0Cj 1-18 Author.......................

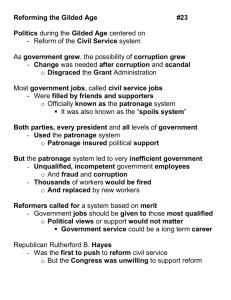

advertisement