USE COLON Submitted to the Department of

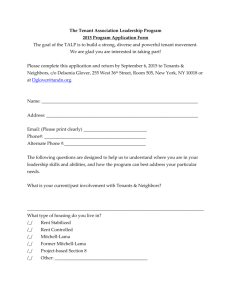

advertisement