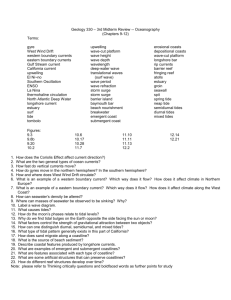

AND CURRENTS IN S.,

advertisement