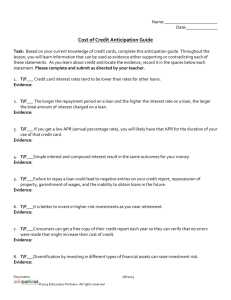

Document 11278353

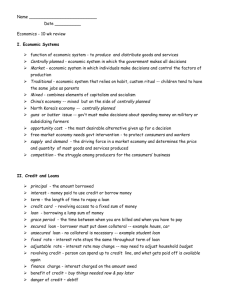

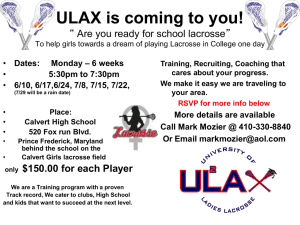

advertisement