BEYOND RECRUITMENT: IN E. GREEN B.A., Political Anthropology

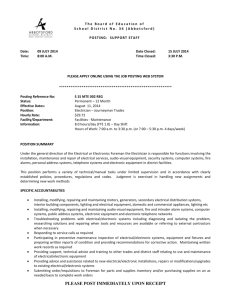

advertisement