Document 11277988

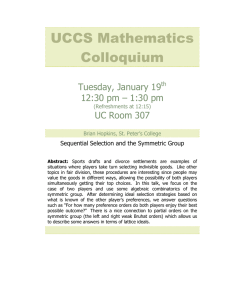

advertisement