STRATEGIES AT by Carolyn R. Brown

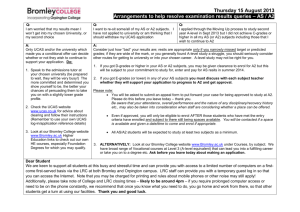

advertisement