GAO DISASTER RECOVERY Experiences from

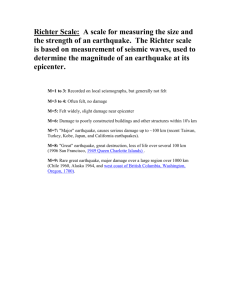

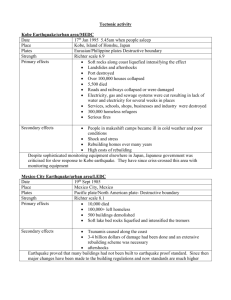

advertisement