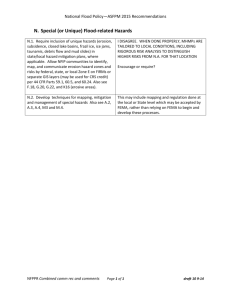

GAO FEMA Action Needed to Improve

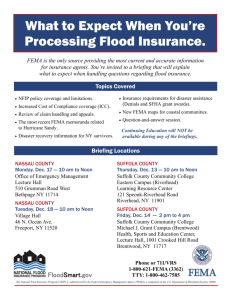

advertisement