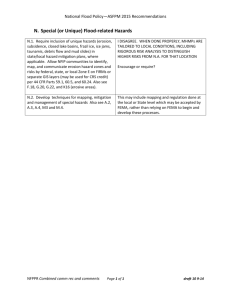

HURRICANE SANDY An Investment Strategy Could Help the Federal

advertisement