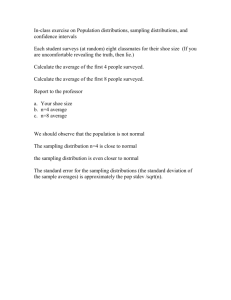

GAO

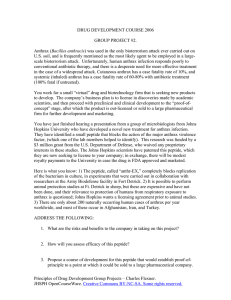

advertisement