GAO CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE PROTECTION

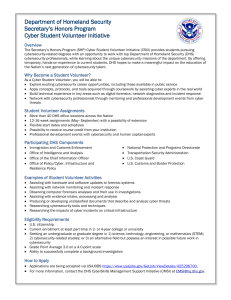

advertisement