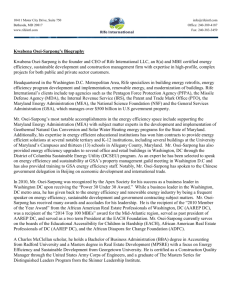

a GAO BUILDING SECURITY Security

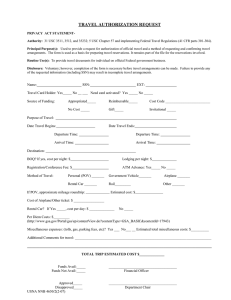

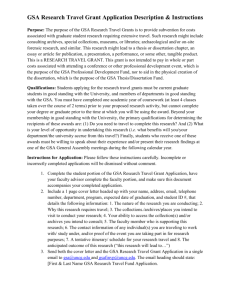

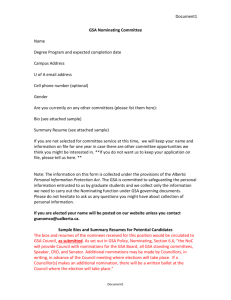

advertisement