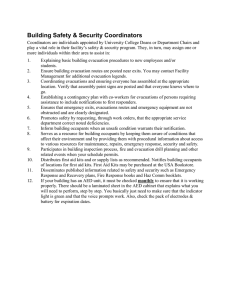

GAO STATE DEPARTMENT Evacuation Planning

advertisement