HOMELAND SECURITY Actions Needed to Better Manage

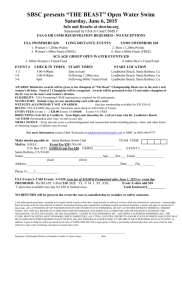

advertisement