GAO CONTAINER SECURITY Expansion of Key

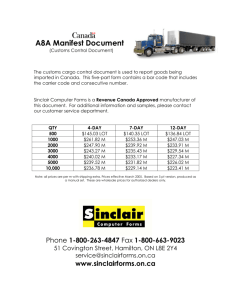

advertisement