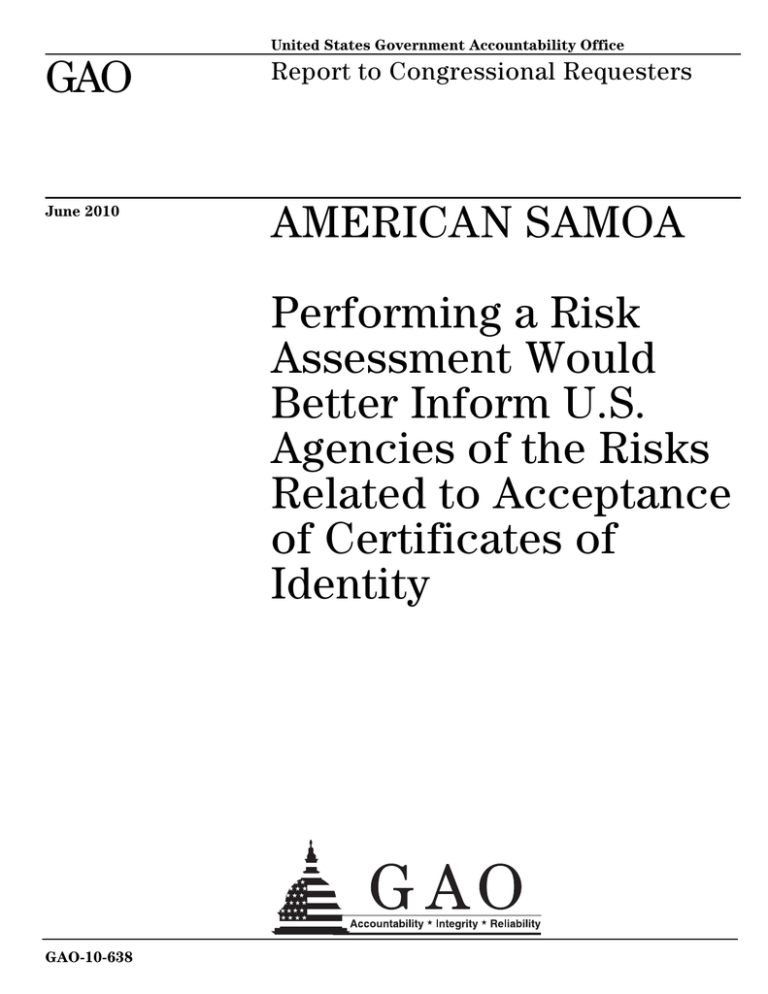

GAO AMERICAN SAMOA Performing a Risk Assessment Would

advertisement