CRS Report for Congress Foreign Terrorist Organizations

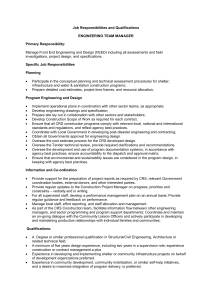

advertisement