The Fed May be Politically Independent, but it is Not Politically Indifferent William Roberts Clark

The Fed May be Politically Independent, but it is Not Politically Indifferent

William Roberts Clark

University of Michigan wrclark@umich.edu

Vincent Arel‐Bundock

University of Michigan

There is a long tradition of partisan analysis of macroeconomic policies and outcome. More than three decades ago, Hibbs (1978), Tufte (date), and Cameron

(1978) launched the field of Comparative Political Economy by arguing that left wing governments serve their constituency best by placing a greater emphasis on fighting employment than inflation. In contrast, right‐wing government are thought to best serve their constituency by placing a greater emphasis on fighting inflation than ameliorating unemployment. Together the implication is clear, Left Wing governments ought to be more eager to adopt expansionary fiscal and monetary policies, while Right wing governments ought to be keen to balance budgets and raise interest rates. This argument is so intuitive that our very definitions of left and right have come to include such difference in macroeconomic policies.

The only problem with this dominant perspective is that it does not appear to be true. There is surprisingly little evidence in support of partisan difference in broad macroeconomic policies or outcomes. Clark (2003) reviews the empirical literatue between Cameron and the late 1990 and finds no studies linking budget deficits or monetary aggregates with the ideology of the incumbent that are not plagued with will established econometric problems. He finds precisely one result linking partisanship with a macroeconomic outcome that avoids these econometric problems: Beck and Katz’s (1993) correction of Alvarez, Garret, and Lange’s (1991) seminal study finds a link between left government and economic growth

(conditioned on the degree of centralization wage bargaining). But the results

Alvarez, Garret and Lange found for a link between inflation and unemployment do

not hold to Beck and Katz’s methodological correction. Clark’s own re‐analysis of

Garret (1998) finds a statistically significant link between partisanship and broad indicators of fiscal and monetary policies and macroeconomic outcomes in about one out of ten statistical tests – which is what we would expect to find under the null hypothesis that there is no relationship.

1

What little evidence can be found for partisan difference in broad measures of monetary and fiscal policy or outcomes is as likely as not to support a counter‐ intuitive – “Nixon in China” – type of relationship where left wing parties preside over higher interest rates and smaller deficits than left wing governments. Casual empiricists have been unable to avoid the glaring presence of record deficits during the Reagan and Bush presidencies. And one recent study (Broz 2011) finds that right wing governments are associated with the “twin deficits” thought to be a harbinger of financial crises (Reinhart and Rogoff 2010).

What explains the dearth of evidence of traditional partisan cycles? What might explain the occasional finding that right wing governments are more profligate than left? In this note we will argue that the answer lies in two places.

First, we believe that while there may be partisan difference in underlying preferences, the vagaries of democratic political competition induce in leaders of all stripes the need to act in a similar fashion. And that fashion is to respond to the tendency of voters to access economic performance in the recent past when

1 It should be noted that some scholars have found a relationship between the ideology of the governing party and either the components of the budget or distribution of tax incidence (Boix date; Franzese date). This suggests that the spending priorities and the preferred revenue source may differ across parties.

deciding whether or not to support the incumbent.

2 This induces all incumbents to act “as if” they prefer macroeconomic expansions in pre‐electoral periods (and, perhaps, macroeconomic contractions in post‐electoral periods). Second, we argue that independent central banks run by “conservative” central bankers are likely to be more eager to thwart the electorally‐motivated expansions by left‐wing governments than right‐wing governments. Consequently, the lack of widespread support for the traditional partisan hypothesis is the result of the fact that ALL parties would like to act like “right wing governments” after elections and “left wing governments” before elections. In the absence central bank independence, there is to stop governments of all ideological stripes from doing so, and so, we observe no different between the parties. In the presence of central bank independence, left wing governments are constrained and/or deterred from attempting to create electorally‐motivate macroeconomic expansions, but right wing governments are

not. And so, under these conditions we observe the counter‐intuitive partisan difference – right wing governments preside over more lax fiscal and monetary policies than leftwing governments. This would also help explain Broz finds a link between right‐wing governments and both fiscal and current account deficits.

If our explanation for the inconsistent and confusing findings on the relationship between the ideological orientation of government and fiscal and monetary policy is correct, what else ought we observe? First, we ought to observe the effect of elections on monetary and fiscal policies and macroeconomic outcomes.

Second, this effect ought to be contingent, in important and predictable ways, on the

2 In the technical language of the literature, voters are “retrospectively myopic” and

“sociotropically economic” in their assessment of candidate performance.

institutional environment policymakers find themselves. Our argument here suggests central bank independence and partisanship of the incumbent government ought to be important modifying variables. Earlier work (Clark 1998, Oately Date,

Clark and Hallerberg 2002) suggests the exchange rate regime is also likely to be important. Third, the strategies pursed by incumbents and central bankers ought

effect which candidates get re‐elected and which ones do not.

We will present evidence in support of all three of these implications – some of this data is knew and some is borrowed from existing projects. Clark (2002) and

Clark and Hallerberg (2002) present evidence of the existence of electoral cycles in monetary and fiscal policy as well as macroeconomic outcomes once one accounts for the fact that the institutional environment a leader finds himself in. Specifically, these studies show that electoral cycles in fiscal policy occur in a sample of OECD countries except when the exchange rate is flexible while electoral cycles in monetary policy occur except when the exchange rate is fixed or when the central bank is independent. These results suggest that democratic political competition does indeed exert pressure on governments of all types to act the same way. Next we will demonstrate that political manipulation. However, our argument suggests that these prior studies are not sufficiently nuanced. Central bank independence should constrain monetary cycles only when the government is controlled by left wing parties. It is important to note that there is nothing that compels independent and conservative central bank to support expansionary policies of right wing governments, but we will argue that they are likely to choose to. To demonstrate that independent central bankers support electorally motivated macroeconomic

expansions if and only if the party in power is a right wing party, we present new evidence from the U.S. case. Specifically, we will show that as elections draw near, the Fed lowers interest rates if a Republican is in the White House, but raises interest rates if a Democrat is in the White House. Finally, we present evidence that – at least from a political standpoint – electoral manipulation of the macroeconomy works ‐ leaders in countries where we expect electoral manipulation of monetary and fiscal policy survive longer in office than leaders in countries where the political‐institutional environment inhibits political manipulation.

Electoral Cycles in Monetary and Fiscal Policy

Evidence for electoral business cycles has been almost as inconsistent as evidence for partisan cycles. Clark and Nair (1998), Clark and Hallerberg (2000) and Clark (2002) argued that the dearth of evidence of electoral business cycles is due to the fact that virtually all tests of the political business cycle argument has assumed that politicians controlled the necessary instruments to engineer pre‐ electoral macroeconomic expansions. In fact, political control of the relevant policy instruments varies across time and space. When capital is mobile, monetary policy

is ineffective when the exchange rate is fixed and fiscal policy is ineffective when the exchange rate is flexible. In addition, central bank independence is thought to take monetary policy out of the hands of elected officials and vest it under the control of apolitical technocrats.

In a data set of OECD countries, Clark and Hallerberg (2000) find that fiscal cycles occur, but only where the exchange rate is fixed (see table 1). They also find

evidence of monetary cycles, but only where the exchange rate is flexible and the central bank lacks independence (see table 2). Hallerberg, Vinhas de Souza, and

Clark find similar patterns in a sample of East European countries in the period prio to EU accession. Clark (2002) presents evidence that these electorally‐motivated manipulations in fiscal and monetary policy translate into links between macroeconomic outcomes and the electoral calendar except when politicians control neither fiscal policy, nor monetary policy – i.e. when the exchange rate if flexible and the central bank is independent. (see table 3)

The Fed May be Politically Independent, but it is Not Politically Indifferent

In the previous section we showed that when politicians control the relevant instrument, they will aggressively use that instrument in an attempt to engineer macroeconomic expansions in the run‐up to elections. Our present argument, however, asserts that possession of a monetary or fiscal instrument is a sufficient, but not necessary condition for political manipulation of the economy.

Rogoff (date) argues central bank independence helps reduce inflation when politicians appoint a central banker with more hawkish anti‐inflationary attitudes than their own. Posen (date) and Adolph (date) argue that central bankers tend to have “hard money” preferences as a result of their close ties to financial market actors. Consequently, as private individuals, it is not unreasonable to suppose that central bankers would have macroeconomic policy preferences similar to what the traditional partisan argument associates with right wing parties. That is, there are reasons to suspect that central bankers are more concerned about inflation than

unemployment 3 and that they lean more towards high interest rates and balanced budgets than politicians in general and left‐wing politicians in particular.

The question is, would central bankers let these views color their behavior in

such a way that it would look like they were rooting for right‐wing parties?

Specifically, would they adopt the very policies they are suspected of opposing in order to help politicians that are nominally committed to the preferences they prefer obtain or retain office? We believe this is an empirical question.

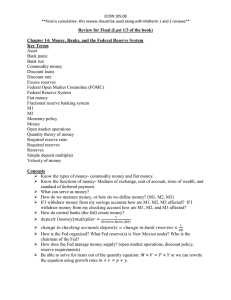

In order to answer this question, we compiled a data set of the Fed Funds rate, dates of presidential elections, party of the president, and a number of macroeconomic control variables. An illustrative look at this data can be had from simple time series plots. Figure one plots the Fed Funds Rate across the forty‐eight months of nine Republican administrations since Eisenhower.

4 While there is a considerable variation, in general, interest rates tend to be higher during the first half of Republican Presidents’ terms than they are in the second half. The dotted line plots the average across the nine administrations and it is clearly downward sloping, There is also a great deal more cross‐administration variance in the first two years of Republican administrations. In contrast, Figure 2 shows that the Fed

Funds rate is generally higher in the second half of Democratic terms and there is more variety in experiences across the Fed Fund Rates early in Democratic terms and convergence toward high interest rates as elections approach. Note that interest rates at the end of the Carter administration were so high that they are not included on this graph. The contrast between Democratic and Republican

3

4 Date for Eisenhower’s first administration is missing before July 1954.

experience can be seen clearly in Figure 3 which plots the average Fed Funds Rate for all Democratic and Republican administrations. Note that interest rates tend to be high (low) during the early states of Republican administrations and low (high) in the later stages. The notion that the Fed accommodates Republican demands for monetary expansions while leaning against similar demands from Democrats

appear to pass the “interoccular trauma test.”

In order to conduct a more formal test of our hypothesis, we constructed a counter variable called Proximity to Election which equals zero in the quarter after a presidential election and rises incrementally until it reaches fifteen in the quarter of the next election. When the central bank is not independent, election‐minded politicians would be expected to lower interest rates as elections approach. If the

Fed is cooperating with Republican electioneering behavior we would expect to see a negative slope on the Proximity to Election variable when we regress the Fed

Funds Rate against it in the sub‐sample of the data where the president is

Republican. If the Fed does not accommodate Democratic electioneering, however, we would expect to see a zero coefficient on the Proximity to Election variable in the

Democratic sub‐sample. Indeed, if the Fed leans against Democratic attempts to use the economy for electoral purposes, we might even see a positive coefficient on the

Proximity to Election variable in the Democratic sub‐sample.

A multiplicative interaction model is an alternative to splitting the sample in

order to test our conditional hypothesis. Specifically, we can estimate:

where R is the Fed Funds Rate, E is the aforementioned Electoral Proximity measure and D is an indicator variable that equals one when the President is a Democratic and zero otherwise. Since the effect of elections on interest rates is given by

it follows that β

1

captures the estimated effect of electoral proximity on interest rates when the president is a Republican (i.e. when D=0 ) and β

1

+ β

3

captures the effect of electoral proximity on interest rates when the president is a Democrat.

Table 4, column 1 presents estimates for the baseline model. Note that the coefficient on the electoral variable ( β

1

) is negative and statistically significant, indicating that with each quarter of a Republican presidential term, the Fed Funds

Rate drops by about 6 tenths of a percentage point. The coefficient on the interaction term ( β

3

) is positive and statistically significant, indicating that interest rates respond differently to the passage of time under Democratic presidents. The sum β

1

+ β

3

is listed near the bottom of the table along with its standard error and we see that it is positive and statistically significant. When the president is a

Democrat, interest rates increase, on average, by about the magnitude that they

drop during Republican terms in office.

One reasonable objection to the results just discussed is that an apolitical Fed

‐ behaving as a benevolent social planner – would be setting interest rates in response to underlying macroeconomic fundamentals and if these are influenced by policy made by parties with different priorities it would not be surprising to find

that the Fed behaves differently when Republicans are in office than it does when

Democrats are. But if the Fed is merely responding to different macroeconomic fundamentals that are correlated with partisan orientation of the President, then these partisan difference should go away after we control for macroeconomic fundamentals. We examine this possibility in second Column of Table 4 where we control for two macroeconomic variables that are widely understood to be factors that the Fed responds to – the inflation rate and the output gap. If the Fed is manipulating interest rates in a textbook countercyclical fashion then interest rates should be raised when either the output gap (the difference between potential GDP and actual GDP) or inflation (which the output gap is thought to forecast) increase.

Not surprisingly, Column 2 suggests that this is the case – the Fed did adjust interest rates in response to the macroeconomic fundamentals. But the conditional relationship between interest rates and the timing of elections seen in Column 1 persist – albeit with an attenuated magnitude – even after controlling for the effects of macroeconomic fundamentals. Thus, while some of the observed correlation between interest rates on the one hand and elections and partisanship on the other can be attributed to the correlation between these political variables and underlying macroeconomic conditions, not all of it can. A partisan bias in Fed policy that is related to the electoral cycle remains. Column 4 considers the possibility that the output gap in the prior period influence current period interest rates through its effect on current period inflation rates. Crucial for our purposes is that the estimates of our key parameters of interest ( β

1

, β

3

) are robust with respect to such specification decisions.

The Political Consequences of Electorally Motivated Fiscal and Monetary

Policies

A brief return to Figures 1 and 2 suggest that if the Fed lowers interest rates in order to help Republicans get re‐elected and raises interest rates in attempt to prevent the re‐election of Democrats they may be quite successful in achieving their goals. In the half century since the “Treasury‐Fed Accord” gave teach to the Fed’s independence by removing its obligation to monetize the Treasury’s debt at a fixed rate, the White House has been occupied by a Republic for almost 2/3’s of the time.

Every Republic president to run for re‐election since the Fed became operationally independent – with the exception of George Herbert Walker Bush – was re‐elected.

Only once was the party of the president able to extend their control over the executive for a third consecutive term – the Bush the elder was elected at the conclusion of Reagan’s second term. In contrast, Clinton was the only Democratic president to serve two full terms after the Fed became independent.

5 While Johnson was also elected to a second term as president, he took over after Kennedy was assassinated during his first term. In contrast, Democrats held the presidency slight more than half of the portion of the 20 th century that preceded the Treasury‐

Fed Accord. While not a single Republican president was re‐elected in the first half of the twentieth century (though Republican presidents frequently succeed each other), both Democratic presidents in the first half of the 20 th century were re‐ elected – Wilson once, and Roosevelt three times. The first Democrat to fail to win

5

re‐election in the 20 th century was Harry Truman – who was also the first Democrat to stand for re‐election after the Treasury‐Fed Accord.

These results are preliminary, but quite suggestive. If the hold up to further scrutiny, they suggest the Fed may be politically independent in the sense that it is insulated from outside pressure – when parties with which it differs over policy place pressure on it to loosen monetary policy it appears to tighten monetary policy.

But it is not indifferent – when the party with which it shares an ideological perspective is in need of pre‐electoral expansion, the Fed appears to accommodate.

In addition, the Republican Party has enjoyed unprecedented success in obtaining and maintaining control over the White House since the Fed became operationally

independent.

Efforts to examine whether a similar dynamic is at work in other OECD countries are ongoing. But we do wish to report some interesting results related to the impact of monetary institutions on the survival of political leaders. Clark,

Golder, and Poast (2011) argue that if Clark and Hallerberg (2000) are correct, then leaders of countries with independent central banks and flexible exchange rates can manipulate neither fiscal, nor monetary policy instruments for electoral purposes.

If the electoral manipulation of these instruments is politically useful, then leaders in such countries ought to experience a higher risk of removal from office. They find that is indeed true, though the benefits of political manipulation are not statistically discernable until leaders have been in office until about seven years.

Table 4 shows that when leaders have been in office for seven years a move away from the baseline case of flexible exchange rates and an independent central bank

involving either a reduction in the degree of central bank independence or the adoption of a fixed exchange rate, reduces the leader’s risk of being removed from office by about 60%. The authors argue this is so because starting from this

basesline, an attack on central bank independence returns control of monetary policy to elected officials, whereas the adoption of a fixed exchange rate renders fiscal policy – already controlled by elected officials in the baseline case – more effective.

The current finds about the partisan nature of the Fed has implications for political survival as well. Specifically, starting again from our baseline case of flexible exchange rates and an independent central bank, a shift to a dependent central bank should clearly reduce the risk of removal from office for left wing leaders. With the central bank dependent, Left wing leaders ought to have relatively free rain to use fiscal policy for electoral purposes – an activity we have argued is impeded by countervailing forces when the bank is independent. But a switch from our baseline case to a dependent central bank ought to a less dramatic effect on the survival chances of Right wing leaders because – if our theory is correct, independent central banks ought to be more willing to accommodate electorally motivated fiscal policies when such policies are adopted by Right wing governments. Figure 4 provides preliminary evidence that this is indeed the case.

Particularly interesting if the fact that a shift to a dependent central bank has a statistically distinguishable reductive effect on the hazard rate of left wing governments during the government’s seventh year in office, but has a statistically distinguishable reductive effect on the hazard rate of right wing governments only

in the 8 th year of Right Wing governments. Central bank independence has greater value for Left Wing governments than right because central bank independence binds the electioneering behavior of Left wing governments, but does not bind the

behavior of right wing governments.

Conclusion

In this paper we have endeavored to show that politicians of both the right and the left will engage in macroeconomic expansions in pre‐electoral periods when given the opportunity. We have also attempt to show that independent central bankers are not indifferent to the electoral fortunes of political parties. There is some evidence from the US that the Fed accommodates pre‐electoral expansions when the Republicans are in office, but do not the same for Democrats. We have also point to evidence to suggest that having an independent Fed in its corner seems to have helped the electoral fortunes of Republicans and Right Wing parties more

generally.

That said, th this may be a U.S. specific phenomenon. Helge Berger and

Friedrich Schneider (2000) showed that the Bundesbank’s policies moved in parallel with changes in the composition of the Bundestag, which is a much more subservient form of politicization of the central bank. Keefer and Stasavage would, in a sense, predict this sort of sensitivity to changes in the composition of the body that, ultimately, grants the bank autonomy and which, therefore, can always take it away. What explains why the Fed can defy its political opponents with impunity?

Part of the answer is certainly the U.S. system’s elaborate system of checks and balances. In a parliamentary system with strong party discipline, a central bank that ignores the preferences of governing parties may find its autonomy restricted with the stroke of a pen. In the United States this is less likely to occur because the

Federal Reserve Act can be amended only with the approval of the President and majorities in both the House and Senate or 2/3 of both houses in the case of a veto over‐ride. Whether our argument generalizes to other countries with independent central banks awaits future research. If that turns out to be the case, it is possible

that our argument could have profound implications for the study of financial crises.

REFERENCES

Alvarez, R. Michael, Geoffrey Garrett and Peter Lange. 1991. Government Partisanship,

Labor Organization, and Macroeconomic Performance. APSR 85:539‐556.

Broz, Lawrence. 2011. “Partisan Financial Cycles” Paper presented at the Political Economy of International Finance Conference, Hertie School of Governance and German

Finance Ministry, Berlin, Germany, February 2011.

Beck, Nathaniel, Jonathan N. Katz, R. Michael Alvarez, Geoffrey Garrett, and Peter Lange.

1993. “Governments Partisanship, Labor Organization, and Macroeconomic

Performance: A Corrigendum.” American Political Science Review 87:945‐48.

Berger, Helge and Friedrich Schneider. (2000) “The Bundesbank’s reaction to policy conflicts,” in The History of the Bundesbank: Lessons for the European Central Bank.

(London: Routledge): 43‐66.

Cameron, David R. 1978. The Expansion of the Public Economy: A Comparative Analysis.

APSR 72:1243‐1261.

Clark, William Roberts. 2003. Capitalism, Not Globalism: Capital Mobility, Central Bank

Independence and the Political Control of the Economy . (Ann Arbor: University of

Michigan Press).

Clark, William Robers, Sona Golder, and Paul Poast. 2011. Monetary Institutions and the

Political Survival of Democratic Leaders. Manuscript, University of Michigan

Department of Political Science.

( http://sitemaker.umich.edu/poast.paul/files/leadersurvival_manuscript.pdf

).

Clark, William R. and Mark Hallerberg. 2000. Mobile Capital, Domestic Institutions, and

Electorally‐Induced Monetary and Fiscal Policy." American Political Science Review.

Clark, William R. and Usha Nair Reichert . 1998 International and Domestic Constraints on

Political Business Cycles in OECD Economies. International Organization . 52:87‐120.

Garrett, Geoffrey. 1998. Partisan Politics in the Global Economy . (New York: Cambridge

University Press).

Hallerberg, Mark, Lucios Vinhas de Souza and William Roberts Clark. 2002. "Political

Business Cycles in EU Accession Countries," with European Union Politics 3:2 (June):

231‐250.

Hibbs, Douglas A. 1977. Political Parties and Macroeconomic Policy. APSR 71:467‐87.

Reinhart, Carmen M. and Kenneth S. Rogoff. 2010. This Time is Different: Eight Centuries of

Financial Folly.

Tufte, Edward R. 1978. The Political Control of the Economy.

Princeton, N.J.: Princeton

University Press.

Figure 1

Federal Funds Rate During Republican

Presidentail Tenures

25

20

15

10

5

0

0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30 32 34 36 38 40 42 44 46

Month

Eisenhower1

Eisenhower2

Nixon1

Nixon/Ford

ReaganI

ReaganII

GHWBush

GWBush1

GWBush2

Rep Avg

Figure 2

Fed Funds Rate during Democratic

Presidential Tenures

6

5

4

3

8

7

2

1

0

0 10 20 30

Month

Note: Does not include Carter Administration

40 50

Kennedy/Johnson

Johnson

Clinton1

Clinton2

Obama

Dem Average

Figure 3

Fed Funds Rate Over Presidential

Tenures, Party Averages

7

6

5

9

8

4

3

2

1

0

1 3 5 7 9 11 13 15 17 19 21 23 25 27 29 31 33 35 37 39 41 43 45 47

Rep Avg

Dem Average

Month

Figure 4 Effect of a shift to central bank independence on the hazard of leader removal, conditioned on party of incumbent.

Effect of Changing from Independent to Dependent Central Bank (Under Flexible Exchange Rates)

Right Governments Only

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Year in Office

9 10 11 12 13 14 15

Left Governments Only

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

Year in Office

9 10 11 12 13 14 15

Table 1 The conditional effects of elections on changes in gross debt in the 1980’a and early 1990’s

Column (1) (2) (3)

Years

Coding of Elections

Election

Capital Mobility

Flexible

Election*Flexible

1982-92

Standard

0.49

(0.60)

-0.20

(0.60)

-0.26

(1.18)

1982-92

Franzese

1.52**

(0.75)

0.14

(0.64)

-1.42

(1.25)

1982-92

Franzese

4.239

(3.341)

0.549*

(0.292)

-0.420

(3.839)

-0.742

(0.855)

Election*Capital Mobility

Capital Mobility*Flexible

Election*Capital

Mobility*Flexible d Debtt-1 d Unemployment d Gdp d Debt Costs

Government Type

Intercept

0.47***

(.10)

1.27***

(.22)

0.38**

(.15)

-0.17

(0.24)

0.67

(0.59)

0.48***

(0.10)

1.27***

(0.22)

0.39***

(0.14)

-0.16

(0.25)

0.35

(0.63)

1.52*

(.75)

0.10

(.98)

0.57

0.69

206

11.320

(8.681)*

0.000

(0.972)

-3.342*

(2.253)

0.442**

(0.109)

1.212**

(0.216)

0.389**

(0.142)

-0.257

(0.256)

-1.098

(1.302)

Conditional Coefficients

Election | Flexible=0

Election | Flexible=1

F

DW

Prob. > F

Observations

0.49

(0.60)

0.22

(0.85)

0.57

0.66

206

0.06

0.99

206

Number of Countries 19 19 19

***p<.01, p**<.05, *p<.10, The dependent variable is the change in the gross debt to GDP ratio. Following DeHaan and Sturm we do not include country dummy variables, although their inclusion does not affect the qualitative results. Note that the political variables (election, the three variables for the type of government, strong finance ministers, and negotiated targets) are evaluated according to a one-tailed test.

F

DW

is the test statistic for Durbin-Watson’s m .

Source: Clark 2003

Table 2 The conditional effects of elections on the money supply in the post-Bretton Woods Era

(1) (2) (3) (4)

Election

Cbi

Fixed

Election*Cbi

Qualitative modifiers

1.070**

(0.499)

1.698**

(0.777)

-1.650

(1.056)

-1.189**

(0.665)

Continuous

Modifiers

0.964*

(0.704)

3.916*

(2.087)

-1.774*

(1.056)

-1.611

(1.734)

Qualitative modifiers

1.558**

(0.725)

6.466**

(3.221)

-0.746

(2.251)

-1.760**

(0.909)

Continuous

Modifiers

2.274**

(0.984)

13.230**

(8.179)

-0.837

(2.242)

-4.802**

(2.325)

Election*Fixed

Cbi*Fixed

Election*Cbi*Fixed

M t-1

Intercept

-0.211

(0.641)

-0.419

(1.341)

1.195

(0.999)

0.797***

(0.027)

2.322***

(0.488)

0.249

(0.581)

0.209

(1.236)

0.488

(0.905)

0.800***

(0.027)

1.718**

(0.670)

-1.025

(0.905)

-7.674*

(4.294)

1.386

(1.373)

13.450

(1.206)***

-0.703

(0.795)

-5.547

(3.633)

1.082

(1.246)

11.926

(2.227)***

F

DW

Prob. > F

38.21

0.000

34.71

0.000

ρ

Observations

Number of

928

16

928

16

0.785

933

16

0.786

933

16

Countries

***p .<01, ** p.<05, *p<.10 one-tailed test used for coefficients involving “Election,” two-tailed otherwise.

Coefficients and panel corrected standard errors. Columns 1 and 2 use Ordinary Least Square Regression with a lagged dependent variable. F

DW

is the test statistic for Durbin-Watson’s m . Columns 3 and 4 use the

Prias-Winsten transformation to remove first-order serial correlation. Columns 2 and 4 use Cukierman,

Webb, and Neyapti's (1992) measure of legal independence and a continuous measure of eroding monetary policy autonomy (see note 18).Columns 1 and 3 use a categorical variable that equals one if the country's score is above the sample median and zero otherwise and a categorical measure of eroding monetary policy that equals one if the exchange rate is fixed and zero otherwise.

Source: Clark 2003

Table 3 Conditional Effects of Elections on Monetary Policy

Central Bank

Independence Flexible

Exchange Rates

Fixed

High

Conditional Coefficients with conditional standard-errors in parentheses. *p< 0.10, **p<0.05, ***p<0.01 Onetailed test

Low

1.56**

(0.725)

0.533

(0.553)

Calculated from Column 3 in Table 2

Source: Clark 2003

-0.202

(0.540)

0.159

(0.922)

Table 4 Summary of Results on Electoral Business Cycles.

Table 14 The Existence of Electorally-Induced Cycles in Macroeconomic Policy Instruments Under

Various Structural Conditions

No Central Bank Independence Central Bank Independence

Capital Mobility and Fixed

Exchange Rates

Fiscal Cycles,

No Monetary Cycles

Fiscal Cycles,

No Monetary Cycles

Capital Mobility and

Flexible Exchange Rates

Monetary Cycles,

No Fiscal Cycles

No Fiscal or

Monetary Cycles

Source: Clark 2003

Table 4 The Effect of Electoral Proximity on the Fed Funds Rate, as conditioned by the Party of the Incumbent President (19532010)

E (Electoral Proximity)

D (Democratic President

E X D

β

1

β

β

3

3

(1)

FEDFUNDS

-0.062

(0.019)**

-2.772

(0.716)**

0.119

(2)

FEDFUNDS

-0.034

(0.017)*

-2.385

(3) (4)

FEDFUNDS FEDFUNDS

-0.044 -0.046

(0.018)* (0.018)**

-2.811 -3.202

(0.655)** (0.686)** (0.665)**

0.066

(0.029)*

0.087 0.084

(0.031)** (0.030)**

Fed Funds Rate t-1 inflation

Output Gap

(0.032)**

0.797

(0.041)**

0.731 0.753 0.679

(0.040)** (0.046)** (0.042)**

0.112

(0.032)**

0.208

(0.035)**

0.125

(0.033)**

Inflation t-1

Output Gap t-1

Constant

-0.012

(0.035)

0.184 0.160

2.575 3.394

(0.038)** (0.038)**

3.760 3.878

(0.622)** (0.561)** (0.654)** (0.623)**

0.057 0.924 1.203 0.038

The Effect of E given

D =1 β

1

+ β

3

Observations

R-squared

(0.022)*

225

0.94

Standard errors in parentheses

* significant at 5%; ** significant at 1%

Administration Dummy Variables not Reported

(0.299)** (0.321)* (0.021)

225 225 225

0.95 0.95 0.95

Table 5

Source: Clark, Golder, Poast (2003)