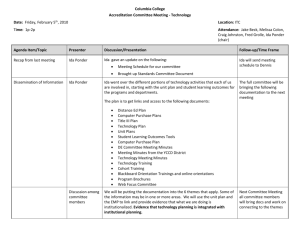

W P N 1 6

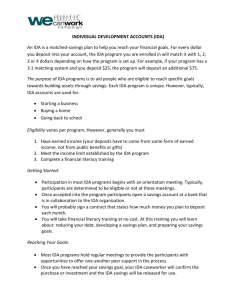

advertisement