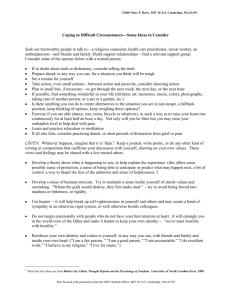

Headquarters on Campus:

advertisement