Document 11267831

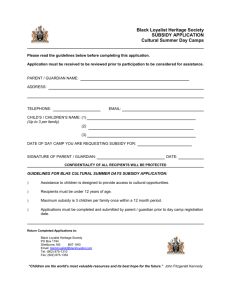

advertisement