Young Deaf Children and the ... S. Science ©

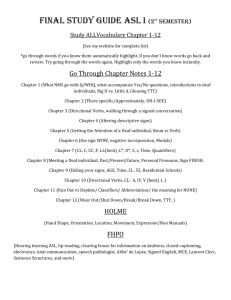

advertisement