Perceived Effects of State- Mandated Perceived Effects of

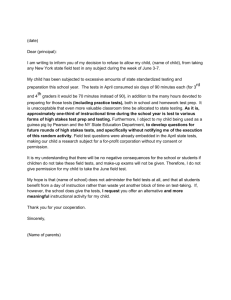

advertisement