Document 11261060

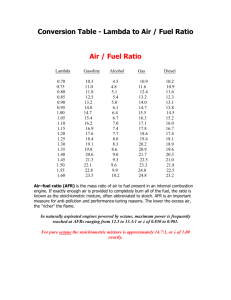

advertisement