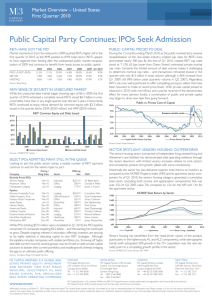

EQUITY REIT IPOs, 1991-1993 by 1986 SUBMITTED

advertisement