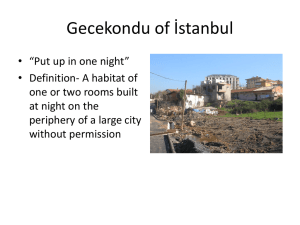

UPGRADING SPONTANEOUS SETTLEMENTS

advertisement