WORKING ECONOMICS MASSACHUSEHS TECHNOLOGY

advertisement

WORKING PAPER

DEPARTMENT

OF ECONOMICS

The Palestinian Labor IVIarltet Between

Gulf

ttie

War and Autonomy

Joshua Angrist

No.

98-05

May

1998

MASSACHUSEHS

INSTITUTE OF

TECHNOLOGY

50 MEMORIAL DRIVE

CAMBRIDGE, MASS. 02142

Digitized by the Internet Archive

in

2011 with funding from

IVIIT

Libraries

http://www.archive.org/details/palestinianlabor9805angr

c:\projects\kschool\kdraft3.wpdMay 18. 1998

THE PALESTINIAN LABOR MARKET BETWEEN THE GULF WAR AND AUTONOMY'

by.

Joshua D. Angrist

MIT

"This study

is

part of the Project

and

on Palestinian Refugees

NBER

at

Harvard University.

I

tiiank the Project for financial

support and the project organizers, George Borjas and Dani Rodrik, for their comments. Thanks also go to Jon Guryan and

Samer Haj Yehia

Archive.

for research assistance.

The data used here

are available

from the Hebrew University Social Science Data

Abstract

were an eventful time in the Middle East. Key events include the Gulf War, the Madrid

peace conference, and the introduction of Palestinian autonomy in all of the Gaza Strip and in most West

Bank population centers. This period also provides the last chance to look at economic conditions in the

territories through the lens of the long-running Israeli survey program, which ended with the transfer of

The

early 1990s

civil authority to the Palestinians.

territories

I

use the Israeli survey data to describe labor market conditions in the

on the eve of autonomy. Special attention

is

given to the impact of changing employment

opportunities for Palestinians in Israel and to the situation of Palestinian refugees. Policy implications of

the findings are discussed.

I.

Introduction

The 1991 Gulf War marked a low

territories

point in Palestinian political and economic fortunes both in the

and abroad. By 1994, however, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank town of Jericho had been

turned over to the newly created Palestinian Authority (PA). In 1995, Palestinian cities and towns in the

West Bank were

also gradually brought under

PA is

relationship between Israel and the

issues

is

how

still

PA control,

although the final economic and political

being negotiated.

One

.

of the most important unresolved

the flow of Palestinian labor to Israel will be regulated or even if it will continue at

The

all.

years 1991-95 were a period of repeated sharp restrictions on Palestinian access to the Israeli labor market,

and, in

These

some

cases,

restrictions

on the flow of goods

were

in

to

and from the

territories (Israel

Employment

Service, 1996).

response to events such as the Hebron massacre and terrorist attacks in

Israel,

sources of variation in economic contacts that need not characterize the Israeli-Palestinian relationship

indefinitely. In the

mean

time,

it is

possible to use the experience of these years to better understand

how

the Palestinian and Israeli labor markets interact.

In three earlier papers (Angrist 1992, 1995, 1996),

Palestinian

for

wage and employment

working

the Israel

in Israel fell

wage premium

working

from roughly 18 percent

rose steeply.

By

in

in Israel increased similarly.

Israeli elasticity

demand

of

model

shows

in

wage premium

that the daily

1981 to zero in 1984. Beginning in 1986, however,

These changes

wage

differential.

fairly inelastic Israeli

for Palestinian labor

The monthly wage premium

parallel the pattern of Palestinian absences

demand curve

specification, but the best-fitting

demand

from

for Palestinian labor.

was estimated by using supply shocks

with security curfews as instrumental variables. FV estimates of

to the details of

number of important changes

1989, daily wages paid to Palestinians working in Israel were 37

work, and are consistent with movements along a

The

described a

patterns since 1981. Angrist (1996)

percent higher than local wages, nearly doubling the 1987

for

I

that originate

equations are somewhat sensitive

models consistently suggest

that the

observed

covariance between Palestinian wages and days worked can be rationalized by a short-run Israeli elasticity

1

of

demand

for Palestinian labor ranging

These

results suggest that labor

possibility that Israeli

demand

between -

1

and -2.

market policies

for Palestinian labor

in the territories

may be

inelastic

should be analyzed

enough

to considerably

earnings loss from reduced access to the Israeli labor market, at least for a while.

On

in light

of the

dampen

the

the other hand,

higher Palestinian wages and an uncertain supply create a strong incentive for Israeli employers to develop

alternative labor resources. Israel's increasing use of non-Palestinian guest-workers to

by Palestinians

now

is

includes as

note that the

fill

an attempt to develop such resources. Recent reports suggest that the

many

as 250,000 guest workers

number of Palestinians working

from Europe and Asia.^ To put

in Israel

positions vacated

Israeli labor force

this figure in perspective,

was probably never more than 120,000

at

any one

time; official statistics indicate between lOO-1 10 thousand workers (Angrist, 1996). Another relevant

piece of background information

is

that in 1995, the entire

only about 1.2 million (Israel Central Bureau of

In light of these recent changes,

it

male civilian labor force

now

seems natural to ask whether

proportional to changes in days worked?

workers on Palestinian wages? This

Another important change

is

numbered

Statistics, 1996).

consequences of negative demand shocks are moderated by

earnings

in Israel

it is still

inelastic Israeli

More

generally,

true that the earnings

demand. Or are changes

what has been the

in

effect of guest

the first set of issues discussed here.

in the Palestinian labor

market that

I

noted in earlier work was a

dramatic reduction in the wage premia paid to more educated workers between 1981 and 1987. Angrist

(1995) provides evidence which suggest that large

shifts in the

supply of educated workers combined with

restricted capital investment explain this decline in returns to schooling. Angrist

different types of workers

schooling coefficients

^This figure

is

were employed

may

reflect

from a recent

in Israel at different times,

(1992) also shows that

which suggests

that these

worker heterogeneity. But the panel data estimates reported

article in the

Hebrew

daily Maariv (1996).

A possible alternative rough

changes in

in

Angrist

indicator of the

flow of guest workers might be had from the number of "temporary residents" (a visa classification) entering Israel. This figure

reached 85,000 in 1996, up from 44,000 in 1995, and 18,000 in 1993 (Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, 1996; Table 4.1).

(1995) show that sharp declines in the returns to schooling are apparent even after allowing for individual

The second

heterogeneity.

more recent

human

issue

look at here

I

is

whether the returns to schooling have recovered

period, perhaps in response to the expectation of increased opportunities for the utilization of

capital

under the autonomy regime.

on the returns

Finally, in addition to updating earlier results

shocks on wages, the third issue discussed in

who Hve

in the

in the

West Bank and Gaza

Strip.

whose

resided in Israel in 1948 and people

this

paper

is

the

economic condition of Palestinian refugees

The TLFS micro data

sets for

1992-95 identify people who

father resided in Israel in 1948.

the children of refugees. Information on refugee status

is

refugee/non-refugee wage and employment gap since

992.

1

and the impact of supply

to schooling

These people are refugees and

used to estimate and characterize the

n. Data and descriptive statistics

The TLFS

In 1967, the Israel Central

Bank and Gaza

territories.

Strip

Bureau of

which was used

The sampling frame was

Because of the

TLFS

rotation

as a

Statistics

(CBS) conducted

a population

Census

in the

West

sampling frame for quarterly labor force surveys in the

periodically updated to reflect migration and

new

construction.

group design, each surveyed household was interviewed four times.

TLFS

interviews were conducted by local Palestinian enumerators employed by the Israeli Civil Administration

in the territories.

The

last

the last interviews in the

survey interviews in the Gaza Strip were conducted in the

West Bank were conducted

in the third quarter

sizes are reported in

Table

1

for selected years through

descriptive statistics and

1989 and every year from 1991-1995.

1994 when the Gaza survey ceased.

Roughly 30-39 thousand interviews were conducted each year

until

The

from a high of 27 percent

fraction of the

sample residing

in the

Gaza

strip fluctuates

quarter of 1994;

of 1995.

The sample used here contains observations on men aged 1 8-64. Basic

sample

first

in

1981-84

to a

low of 22 percent

in

1988.

The mean age of men

Approximately half of the men

in the

in the

sample

is

stable at about 33.

sample are wage laborers, the remainder being mostly

employed (including work on a family farm or business), unemployed, or

constitute 2/3 of the labor force, with participation rates ranging

men

in the labor force

who were employed

This ranges from 37-39 percent until 1993,

shows

that

skilled

and unskilled jobs, and

workers from the

territories

in Israel or

when

who

are

it

Jerusalem

sample rose from 7.7 years

in

shown

is

in Israel

and agriculture

Kleiman (1992) and Semyonov and Lewin-Epstein (1987). Table

level in the

to

Wage

laborers

82 percent. The fraction of

in the last

column of Table

1.

drops sharply, to 32 percent. The lower half of Table

employed

in the construction

from 72

in school.

self-

1981 to 8.7 years

and Jerusalem are concentrated

industries.

1

in 1991,

also

For more on

shows

1

in semi-

this point, see

that the average schooling

and then continued

to rise to

over 9

years in 1993.

For the purposes of this paper,

in the State

of

Israel.

I

define a first-generation refugee to be

someone who

1

indicate that in

Bank and Gaza

Strip,

1992 and 1993, the

when complete

last years

about 5 percent of the

men

in the extract

percent were second-generation refugees. Weighting this by

proportion of second generation refugees to 30.5 percent.

Gaza

Strip than in the

1

948

A second-generation refugee is someone whose father lived in the State of Israel in

1948. These definitions correspond to the information collected in the TLFS. Estimates not

Table

lived in

first

generation refugees.

in

surveys were done in both the West

were first-generation refugees and about 23

CBS

sampling weights increases the

The proportion of refugees

West Bank. About 54 percent of Gazans

refugees and 8 percent are

shown

is

much

higher in the

are estimated to be second generation

The corresponding

figures for the

West bank

are 16

and 3 percent, respectively.

The usual

TLFS.

types of sampling and non-sampling errors in labor force surveys are also present in the

In addition, data collection after

territories that

1988 became more

were part of the Palestinian uprising or

difficult

Intifada.

because of civil disturbances

Because

TLFS

in the

data on the territories were

collected

by employees of the

Israeli civil administration, these

may be

data

less accurate

than data from

comparable labor force surveys carried out elsewhere. Moreover, although there are many sensible

patterns in the

TLFS

data on labor force status

(e.g., seasonality;

wages are

see Angrist, 1996), data on

often poor even in the best circumstances.

As

a check on the

TLFS

data.

Table 2 reports estimates of average wages from the

first

two waves

of the Palestinian Labor Force Survey (PLFS), which was conducted in the third quarter of 1995 and the

PLFS wages

second quarter of 1996.' Average

employed

49 shekels

locally (including Jerusalem),

for Palestinians

employed

in

1995 were 35 shekels for residents of the West Bank

27 shekels for residents of the Gaza Strip employed

in Israel (excluding Jerusalem). Estimates

second quarter of 1995 are about 31 for Palestinians employed

The most

shekels for Palestinians employed in Israel.

quarter of 1994;

when

the average

wage

is

in the

recent Israeli

from the

and

locally,

TLFS

in the

West Bank or Jerusalem and 51

wage data

estimated to have been 26 shekels.

for

Gaza

So

the

is

from the

PLFS and

first

the

TLFS

data seem to generate estimates that are in the same ball park.

There were no

at all locations

following the

Israeli

surveys in the territories in 1996.

between 1995 and 1996. This drop

November 1995 Rabin

is

in

wages

probably due to the disruption of economic activity

assassination, the early

subsequent closure and quarantine of the

The PLFS data show a big drop

1996 bus bombings

territories until the elections in

in Israel,

and the

May.

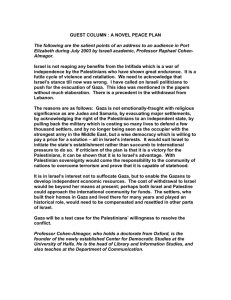

Graphical analysis

After an

initial

decline during the Palestinian uprising, the proportion of Palestinians working in

Israel fell sharply in 1993, largely as a

Israel.

The change

in probability of

consequence of an increasingly

working

in Israel can

be seen

'These estimates were derived from Palestinian Central Bureau of

reports suggests an effort has been

sometimes reported on a different

made

basis.

to maintain

in

Figure

Statistics

some comparability with

restrictive access policy

1

(1996a,

,

enforced by

separately for residents of

b).

The

introduction to these

the Israeli surveys, although the

PLFS

results are

the

West Bank and Gaza

employment/population

Gaza

Recent changes

Strip.

ratios.

These also

fell

Strip to levels not substantially different

Bank employment

unemployment

rates also

rates,

seem

to

employment

in

in the

West

On

have recovered by the end of 1995.

data

show

in

Figure

from those prevailing during the preceding

which are affected by movements

TLFS unemployment

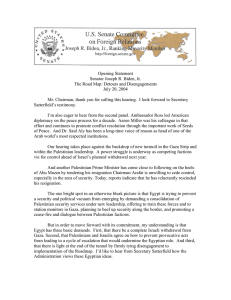

can be seen

2,

which

plots

sharply in early 1993, but recovered very quickly in the

in

and out of the labor

early 1993 than they had been previously, especially in the

most recent

rates

rates

the other hand,

force, stayed higher after

West Bank. This can be seen

around 4 percent

in the

West

years.

Gaza

Strip

in Figure 3.

The

and around 7 percent

Bank."*

Figure 4 plots average days worked by region of residence.' Like the employment data, this figure

also

shows a sharp drop

in

1993 that was almost as large as the Gulf War drop. Subsequently, average

days worked seem to have returned to the 18-19 day level prevalent during the Intifada period. Figure

which

plots average days

worked by work

shows

location,

that reductions in average

5,

days worked

continued to be most severe for those employed in Israel or Jerusalem. In contrast, average days worked

appear to have been on a gradual upward trend for those employed

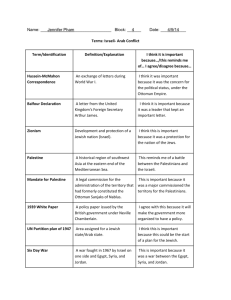

In recent years, the pattern of fluctuations in

days worked, although

it is

somewhat

quarter changes in average days

I

have also confirmed

this

6,

which

worked occurred

at

in

plots

by comparing quarter-to-

worked and average monthly earnings. This comparison shows

recent years at least, changes in days

that

5.

monthly wages largely mirrors the fluctuations

This can be seen by comparing Figure

less volatile.

monthly wages by work location, with Figure

locally.

roughly constant real (daily) wage

changes in monthly wages are roughly parallel to changes in days worked

is

that in

rates.

The

fact

important because this

implies that fluctuations in days worked are not associated with changes in wages.

"•The

TLFS

labor force status recode from which the

similar to those used in the

'Figures that plot information by region of residence

work

location.

unemployment

rate is constructed uses "actual status" definitions

CPS.

Figures that plot information by work location

regardless of region of residence.

show averages for all workers who live in the region, regardless of

show averages for all workers employed at that location,

The

fell

wages of Palestinians increased steeply from 1985

to 1989, fell

from 1989

to 1991,

and

again in 1993. This can be seen in Figure 7, which plots average daily wages by work location. This

figure also

the

real

first

shows

that the

wages paid

employed

to Palestinians

half of the 1990s and declining in Gaza.

in the

But wages paid

West Bank were more or

to Palestinians

working

less flat in

in Israel

or

Jerusalem exhibit an increasing trend from 1991-95. Only in 1995 do wages paid to Palestinians working

in Israel turn

down

the increase in

again, for the first time since 1991 (except for first quarter 1993). Note, however, that

wages paid

to Palestinians

working

in

Jerusalem

is

somewhat more gradual

after 1992.

Interpretation

The

years 1992-95 were

migrant labor to

under curfew, as

on the

Israel.

marked by extended and repeated

In 1992, 1993,

in the Intifada years.

territories instead

interruptions in the flow of Palestinian

and 1994, there were periods when large numbers of people were

It is

also important to note that Israel increasingly

of curfews, so that curfews were not the only or even the most important source of

supply shocks. There were

total closures

of the territories in April 1993, February 1994, April 1994,

October 1994, January 1995, July 1995, August 1995, and September 1995

1996).

The

imposed closures

closures lasted from one

Palestinians were allowed to

work

week to up

to

(Israel

Employment

Service,

two months, during which time few and sometimes no

in Israel or Jerusalem.

During the Intifada years (roughly 1988-91), exogenous supply shocks were associated with an

increase in daily wages. This

wage response

partly offset the decline in earnings

so that earnings were less variable than wages.

wages

in the

more recent period suggests

workers as they used to be.

It

The

that Israeli

fact that earnings appears to

from fewer days worked,

be about as

volatile as

employers are no longer as dependent on Palestinian

should be noted, however, that the period discussed here largely predates the

massive inflow of guest workers to

Israel,

which probably did not begin

apparent insensitivity of wages to fluctuations in days worked

in earnest until 1995.

may therefore

The

reflect a structural

and

perhaps long-lasting change in the Palestinian-Israeli employment relationship.

Real wages earned by Palestinians working in

95 period, only beginning

to decline in 1995.

probably reflects post Guif

wages

in

The growth

War economic growth

1995 may indeed be due

Israel increased substantially

wages paid

in

in Israel.

On

to competition with the guest

over most of the 1992-

to Palestinians

the other hand, the

working

dechne

in Israel

in Palestinian

workers since the IsraeU economy

continued to grow in that year. In contrast with the decline in Palestinian wages between 1994 and 1995,

enjoyed real wage growth of about 2 percent over

Israeli citizens

Statistics,

1996; Table 12.24).

It is

still

period (Israel Central Bureau of

and 1993, when the wages paid

also worth noting that in 1992

Palestinians working in Israel and Jerusalem were

essentially

this

wages of Israeli

increasing, the

citizens

to

were

flat.

in. Regression estimates

and changes

in schooling coefficients

This section uses regression models to show that the pattern in relative wages seen in the figures

is

apparent after controlling for basic demographic characteristics, and to look at recent changes in the returns

to schooling.

Table 3 reports the results of estimating the following equation (computed by weighted

squares using

CBS

sampling weights):

log(wJ =

where

is

6^, is

in-Israel effect in year

term

Xi(aot

-i-

+

Xi,ao,

is

a

Xi,^(x,t is

more

t, aj^

is

a

+

^

aiePc

dummy

+ Zg

+

bigYg.

f.Qt

variable indicating if

i

t, fj

is

a

dummy

variable indicating if

i

works

Cj

is

a

dummy

variable indicating if

i

lives in

variable indicating

work

in

+ C-X +

variable that indicates if

dummy

is

i

in schooling

Jerusalem and

i);

],\\i+ u^,

is in

are:

(1)

age group c and P„

group g and

in Israel in year

t

and

Ygt is

6t is

an urban area and X^

is

is,

8

a work-

a city effect

The

Xit=ageit-years of

25-34, 35^44, 45-54, 55-64. The schooling groups indexed by g

years.

is

a

a work-in-Jerusalem effect.^

a time-varying quadratic function of potential experience (that

'The age groups indexed by c

years, 16 or

Xi,'ai,

a

t,

dummy

+

bjg is

t,

schooling effect in year

t, Jj

Sq,

a quarter effect in year

an age effect in year

in year

least

are:

13-15

schooling|,-6).

Column

Table 3 reports estimates of the daily wage premium for working

(1) of

of residence. The premium

fall

sharply from about 20 percent in 1981 to -.03 for residents of

Bank

1984, and to .056 for residents of the West

.25 for

1994

Gaza

at

residents in

1987 and

both work locations. In

in Israel

to .20 for

fact,

in 1984.

The

West Bank. The

the 1992-1995

Israel

premium

by region

Gaza

in

rose sharply after that, to

increase continued every year from 1991 to

wage premium

for

work

in Israel

was

larger than

it

has ever been. The 1995 premium was about 50-60 percent for Palestinians from both locations.

The schooling

locations,

coefficients

and continued

shown

to decline in the

in

Table 3 decline monotonically

West Bank

thereafter.

But beginning

schooling began to increase substantially for residents of the Gaza Strip.

also increased in 1995 for residents of the

investment and the increase in

until

The

West Bank. This turnaround may

1991 for residents

in 1992, the returns to

returns to a college degree

reflect

1

993

in

an inflow of

and administrative jobs generated by the autonomy process.

civil service

PA administrative activities were concentrated in the Gaza Strip during this period,

in the returns to schooling in

both

at

Gaza pre-dates

the official beginning of

although the increase

autonomy

there.'

Finally, note that in contrast with the specification reported here in Table 3, potential experience

was not included

in the

models reported by Angrist (1995) because exact years of schooling are poorly

measured. But the specification used here

otherwise identical to the ones

is

I

used

potential experience necessarily raises the estimated returns to schooling but has

period comparisons. This can be seen in the second panel

equation (1)

when

the potential experience quadratic

rV. Changes in Refugee/non-Refugee

wage

'The Declaration of Principles was signed

The preparatory

transfer of

power

of Table

3,

little

effect

Including

on cross-

which reports estimates of

dropped (and age dummies are retained).

differentials

Table 4 reports estimates of differences

1994.

is

B

earlier.

in

in other areas

in daily

wages between refugees (men who residing

September 1993 and the Gaza/Jericho withdrawal was completed

was completed in December 1994.

in the

in

May

State of Israel in 1948), the children of refugees

and other Palestinians. Refugee

effects)

fathers resided in the State of Israel in 1948),

models without controlling for covariates (other than period

were computed by estimating:

log(W;,)

where

effects in

(men whose

R,i, is

a

dummy

=

6^,

+

+

R,i,(t)„

for refugees

and

R2i,(|)2,

Rj,, is

a

+

(2)

Ui„

dummy

corresponding refugee effects. Estimates with covariates were produced by adding

equation

1992 and 1993, refugees earned

The 1992 refugee wage gap was about

the

wage gap was about

Strip,

less than

8.5 percent in

4.5 percent in

model (including controls for work

Gaza

Gaza and

Unlike

in the

West Bank. The

first

covariates.

Gaza and

15.7 percent in the

15.3 percent in the

+

(j)2,

are the

R2i,4'2i to

gap

in

Bank and Gaza

Strip.

West Bank. The 1993

West Bank. Adding

covariates to

both years to less than 2 percent in the

Gaza

Strip in

In the

1

covariates-adjusted gap between refugee and non-

percent.

Gaza

generation refugees residing in the

covariates are not taken into account,

in the

non-refugees in both the West

location) reduces the

refugee wages in 1992 and 1993 was around 8-1

men

RntCJ),,

and

an amount less than the standard error of the estimates. Including covariates also reduces, but

does not eliminate, the gap

when

(J),,

(1).

In

refugee

and

for the children of refugees,

1992 and 1993. This appears

West Bank, however,

same when estimated with or without

other Palestinians in the

men whose

West Bank

From 1992-1995,

the

is

the

wage gap

covariates.

Strip,

fathers

to

who

earned less than other Palestinians

were refugees earned no

less than other

be the case with and without controlling for

for first

and second generation refugees

is

about the

The wage gap between second generation refugees and

also largely unaffected

raw refugee wage gap

in the

by control for covariates.

West Bank

fell

from -.16

to -.05. This

is

apparently due in part to changes in personal characteristics. Controlling for covariates, the gap shrinks

much

less.

years.

So

The 1995 gap

for second generation refugees in the

the overall pattern suggest that refugee

West Bank

wage gaps have been

10

is

also smaller than in earlier

closing.

The data

for residents of

the

Gaza

Strip actually

show an

than other Palestinians in that year. But this

1994 survey

in

more

interesting turnaround in 1994, with refugees earning substantially

Gaza was conducted

may be an anomalous

result

which

reflects the fact that the

Also, the 1994 interviews in

in the first quarter only.

Gaza were

the

before the Israeli survey program ended there, and this quarter marks the transition from Israeli to

last

Palestinian authority.

Table 5 reports estimates for employment similar to those reported in Table 4 for wages. The

employment models with covariates do not control

story here

similar in

is

many

refugees residing in both the

Palestinians.

much

of the

for

work

respects to that for wages.

West Bank and Gaza

location since

When

Strip are

some men do not work. The

comparisons are not adjusted for covariates,

much

less likely to

be working than other

But adjusting for education, age, urban residence, and potential experience accounts

first

generation refugee employment gap, especially in the

covariates also reduces the refugee

employment gap

for residents of the

Second-generation refugees in both the West

gap remains

substantial.

employment

rates than other Palestinians, with

difference between the results for wages and

Gaza

Strip.

Controlling for

West Bank, although

Bank and Gaza

and without adjusting for demographic

employment

have been shrinking, the employment gap does not appear

is that,

to

unlike the

wage

for

Strip

the adjusted

have lower

characteristics.

One

gap, which appears to

have changed systematically

in the

1992-95

period.

V.

Summary and

policy discussion

Summary

Three important characteristics of the Palestinian labor market are the wage premium for working

in Israel, the

economic returns

to schooling,

and the refugee wage and employment gaps. For most of the

period since 1991, the wages of Palestinians employed in Israel were rising, while local wages were

The

(log)

premium

for

working

in Israel in

1992-95 reached 50 or 60 percent as the

11

Israeli

flat.

economic

improved while

situation

roughly proportional to changes

change

begun

wage

in

to

fall.

served to

in

Moreover,

rates.

Recent changes

that in the territories did not.

monthly earnings have been

days worked, suggesting that labor supply shocks did not induce a

wages of Palestinians employed

in 1995, the

in Israel

appear to have

were associated with increasing wages, which

In the past, negative labor supply shocks

dampen

in

the consequences of these shocks for earnings and offered evidence of Palestinian

market power in the market for construction and agricultural workers. Overall, the new findings suggest

that the

dependence of

Israeli

now been

employers on Palestinian labor has

reduced, perhaps because of

The question of whether

guest workers, sectoral shifts, or substitution in favor of capital or local labor.

new

situation

is

permanent or transitory remains open.

Other findings suggest that the returns to schooling

sustained decline, although there

pre-Intifada levels.

On

is still

way to go

a long

Palestinians have been concentrated in the

West Bank, once

The

(1996),

Strip.

I

last set

Gaza

of relationships looked

the other hand, there are

at

Gaza

Strip

West Bank

new employment

Perhaps a change

Strip.

began

before the returns on

the Palestinian political infrastructure there

do not find dramatic differences

On

in the

the other hand, educated workers in the

for their schooling. Together, these findings suggest that

the

is

more

to recover after a

human

still

capital reach their

receive almost no

in opportunities will also

percent.

to

established.

market conditions by refugee

some important

however, the adjusted refugee wage gap

come

here are refugee/non-refugee contrasts. Like Pedersen

in labor

than other Palestinians, although the refugee

premium

opportunities for skilled

status, at least in the

differences, especially for residents of the

wage gap appears

in the

to

have been declining. As

West Bank was about 7

The adjusted employment gap

in the

Gaza

12

Strip in

percent, while the

Gaza

West Bank.

Refugees and the children of refugees in the West Bank have lower wages and lower employment

was 4-6

the

late as

rates

1995,

employment gap

1994 was about 7 percent.

Implications for access policy

Structural

Israeli labor

economic changes are almost by definition

long-lasting.

If a structural

market has occurred, then the Palestinians should probably not count on returning

arrangement that allows large numbers of migrant workers to commute to work each day

other hand,

change

if

the

new

relationship

between Palestinians and

by guest workers, prospects for a

Palestinians have been replaced

makers and many commentators

(see, e.g,

Maariv,

1

homes

in the

an

in Israel.

On

the

employers has developed because the

reversal

seem

better.

Israeli policy

996) appear to be uncomfortable with the notion of a

permanent guest worker population; Palestinian workers,

the most part return to their

Israeli

to

in the

at least,

West Bank and Gaza

do not aspire

to Israeli citizenship

Strip every evening.

This

is

and for

a remarkable

and perhaps even unique feature of Palestinian labor migration.

The question remains whether either

number of Palestinians working

Palestinians

employed

in Israel

in Israel as a desirable

must surely be

employers benefit from low cost employees

Moreover,

little

Israelis or Palestinians

outcome. The large wage premium

attractive to workers.

who

are, in

premium apparently need be paid

for

should look to an increase in the

many cases,

more educated

And even

at these

now enjoyed by

wages

Israeli

highly skilled and productive.

Palestinian workers.

On

the other

hand, employment of workers from the territories involves substantial transaction costs on both sides. For

the workers,

employment

in Israel involves long

commutes even though

distances are short (see, e.g.,

Angrist, 1996), as well as arbitrary search and seizure, risk of personal attack, and lockouts in response to

attacks or as a

consequence of local quarantines and curfews. Employers pay a price

in terms of

uncertainty and employee absences, sabotage, and the risk of personal attack.

In addition to these considerations, data

from other countries show

economic integration has increased, migrants from developing countries

analogy appropriate in the

Israeli case) constitute

In a recent study of labor in the world

that while international

to industrialized countries (an

only a modest proportion of the world stock of migrants.

economy. Bloom and Brender (1993)

13

note:

"World economic integration has proceeded even though international labor mobility has

not increased in recent decades

.

.

.

Developed country governments generally do not

encourage international migration and often inhibit

legal or financial barriers

.

.

.

limitations

through the imposition of various

it

on the physical mobility of labor, however, have

not prevented the emergence of a global market for labor services as services can be

exchanged

in a variety of

ways

that

do not require the physical proximity of buyers and

sellers."

This suggests that there are a variety of economic and social factors that limit the benefits from migrant

labor.

In fact, the experience of developed countries around the world

at

who have employed

one time or another has been mixed. Recent examples of non-citizen labor

include

US employment of Mexicans, German employment of Turks,

citizens of

in

migrant labor

developed countries

Western European employment of

Southern and Eastern European nations, and Malaysians employed

in Singapore.

In each of

these cases, pressure has been generated for change in one or both of the following directions: (1) Granting

the full range of civil rights and social benefits to migrant workers, with the possibility of eventual

citizenship.

A leading example is the situation of long-time resident Turkish guest workers in Germany;

(2) Substitution of capital mobility for labor mobility.

manufacturing from

Hong Kong

one hand, under the

1

here

is

the recent flow of capital and

to Southeastern China.

Recent American experience

On

An example

is

especially interesting because

990 Immigration Reform and Control Act,

it

reflects

moves

illegal aliens

in both directions.

who have been

country from a long time can in some cases apply for amnesty and permanent residence.

hand, efforts have been

the

made

Rio Grande. In addition

program

is

the Offshore

to

to

encourage American firms to

low labor costs and proximity

Assembly Provision of the

US

14

tariff

set

to

On

in the

the other

up establishments on the Mexican

side of

American markets, a key component of this

schedule which stipulates that products

assembled or processed abroad with

The Mexican government

value added.

when

the

US

US

closed

down

parts are levied an import duty (to the

originally

promoted

US

US) only on

the foreign

offshore assembly to offset job losses

a program that permitted seasonal entry of Mexican farm workers (Mendez,

Murray, and Rousslang, 1991).

An

analogous "offshore assembly" effort for Israel would be to promote Palestinian industry and

agriculture in 4he territories, integrated with Israeli distribution and marketing, as an alternative to labor

migration. This process will probably develop faster

employing Palestinians or foreign guest workers

employers do not have the option of

if Israeli

in Israel.

In the past, Israeli policy

makers seem

to

have

found local Palestinian economic development a threatening prospect but lessons from other countries

suggest that this need not be the case.

Some

of the features that make Gazan labor attractive to

employers apply equally well to the employment of Gazans

Gaza using

in

Israeli

Israeli

and other foreign

capital.

Recent research on the determinants of foreign direct investment also suggests that for developing

countries, infrastructure, stable international relations, rapid industrial development,

domestic market are the factors most important for attractive capital from abroad

than tax concessions and low labor costs (Wheeler and

Two

Mody,

and an expanding

- more

important even

1992).

other policy issues

I

conclude with a brief discussion of the policy implications of the two others

reported here.

My study of the returns to schooling (Angrist,

political reasons for the decline in

capital

1995) in the

economic returns on human

have begun to recover for workers

who

live in the

Gaza

capital.

territories

returns to

human

capital, either

may want

discussed possible

In fact, the returns on

Strip, possibly

human

because of autonomy.

the other hand, the returns to schooling remain had not yet turned around in the

the near term, the Palestinian leaders

sets of findings

West Bank

to consider efforts directed at reducing the

On

as of 1995. In

imbalance in

by changing the geographic distribution of public sector employment or by

15

making investment

in the

West Bank more

attractive.

Of course,

the success of such efforts depends on a

range of external factors that are impossible to control.

Finally,_the results for refugees suggest that refugees

only moderately worse off than other Palestinians.

(1996).

While the

results reported here

rates than non-refugees, the

wage gap

is

show

who

reside in the

West Bank and Gaza

A similar conclusion was reached recently by Pedersen

that refugees

closing and the

have somewhat lower wages and employment

employment differences

are not dramatic. This

suggests that resources devoted to further integrating refugees into the local Palestinian

most effective

overall

if

are

economy way be

they are focused on improving schools and physical infrastructure and on boosting the

macro economy,

as

opposed to programs of targeted subsidies and

16

transfers.

References

"Wages and Employment in the West Bank and Gaza Strip: 1981-90," Falk Institute for

Economic Research in Israel, Discussion Paper No. 92.02, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, July

Angrist, J.D.,

1992.

"The Economic Returns to Schooling in the West Bank and Gaza Strip," American

Economic Review 85 (December 1995), 1065-1087.

Angrist, J.D., "Short-run Demand for Palestinian Labor," Journal of Labor Economics 14 (July 1996),

Angrist, J.D.,

425-453.

Bloom,

D.,

and A. Brender, "Labor

in the

World Economy,"

NBER Working Paper No. 4266, January

1993.

Israel Central

Bureau of

Statistics,

Labour Force Survey

in

Judea and Samaria: January-September 1995,

Jerusalem: September, 1996.

Israel Central

Israel

Bureau of

Employment

Abstract of Israel 1996, Jerusalem: 1996.

Payments Division, Dates of Closures 93-94-95, Memo dated January

Statistics, Statistical

Service,

15,

1996.

Lewin-Epstein,

Noah and Moshe Semyonov. The Arab Minority

Inequality.

in Israel's

Economy: Patterns of Ethnic

San Francisco: Westview Press, 1993.

Kleiman, Ephraim. "The Flow of Labour Services From the West Bank and Gaza to

Israel." Department of

Economics Working Paper No. 260, Hebrew University, Jerusalem, July 1992.

Maariv (Hebrew Daily), "Foreign Workers: Underground Israel '96", Saturday Supplement, pages 14-20,

October 25, 1996.

A., T. Murray, and D.J. Rousslang, "US-Mexico Employment Effects of Repealing the

Offshore Assembly Provision," Applied Economics 23 (March 1991), 553-566.

Mendez, Jose

Palestinian Central

Bureau of

Statistics,

US

Labour Force Survey: Main Findings (September-October 1995

Round), Labour Force Survey Report Series (No.

1),

Ramallah: April, 1996.

Bureau of Statistics, Labour Force Survey: Main Findings (April-May 1996 Round),

Labour Force Survey Report Series (No. 2), Ramallah: August, 1996.

Pedersen, Jon, "West Bank and Gaza Living Conditions: Are Refugees Different? (the answer is: not very

much), paper prepared for the Harvard Refugee Project, October 1996.

Wheeler, David, and Ashoka Mody, "International Investment Decisions: The Case of US Firms,"

International Economic Review 33 (August 1992), 57-76.

Palestinian Central

17

;

'

E

»rj

Tt

a

*

6

—

o

^

-*

—

^

O

o

rf"

fi

—

oo

•a

Q

5

°-

—

tN

—

—

5'E

2

t_

t?

13

c«

OS

oi

2

o

o

f^

-

c

u O

cr^

c

o

c

p

CT;

—

c*S

r^

vo

^

0>

00 •a

4>

rt

" o

o

a

'd

,:

>>

p

so

r*i

00

q;

•H

u « 5

S *

.^

C3

E'd

.,-

i5

a B o

o

to

8

u c

=*

lis

U~t

C

—

°

.°

S2

^

CO

set

o o

s E a

a*

—

OS

—

^

o

—

<

—

o

oo

—

S a o

lic

o

V]

tf

o

u « g

a.

?J

E a

i

_-

=03

CL

E

OS

in

—

'

—

—

^^

i

T3

O =

ca

c

03

U

—

S

E S «

en

n

as

o^

-*

—

*

03

d

-'

n

2

2

d

o^

1

o ?

c

^^

C

C 3

"E.

iSt

ia

<u

&

2

"5

^

in

a

u

a.

£

o

<

z

<

z

p

O

•a

c

o

o o

Z

.t

I

la

^^

m <3

—

o

U-l

"^

to

o

-*

o

^

— o

r^

O Tt

— o

— "^

oo

*

— o

CO

ifi-a

vn

M

;S

r^ oo

<N

o

(N »n

<N

O

^-1

o

O

u

oo oo

oo

*-

^ o

o

^-

D

u

O

<

vj->

^ & o ;_

uU O ;^

(N

Tt

„H

m

o

^H >i-l

\D (N

Tf

O

—

CS

csi

O

O O

— o

'

O ON

—o

O

T

S

o

mm

o

§

•^

oo

—o

«

mo

m

(N

oo (N

oo

rr\

— —

Tj-

I

rj oo

^

m

O o

—

o

(N —

•* O

^- oo

XT) ^~

OO

oo

o

—

O

—O

^"

D

— o

CM

»n

O

o

s:00 ,o

o

U

^§

k.

OJ

-r

s

rncNt

'OfNl

TtO

o

f*^

^-

(SO

r^—

f^O

On^O

oo—

— O

c^^/^

oo—

—

m

-o —

xn

—

^O

^ (N

o o

82

q

o

_

°o

P o

oooo

-^

OO

P

OO

—

oo

^

P O

oo

CN OO

»o

o

oO

5 ^

MD -J

P O

<2

O

<

z

o

—

mo

u

cs

oo (^

-r

oo

en

O

S •o:9'

li-)

p-i

o>n

r^(N

^o

-rt

oo rs

<M

O

r--—

•

ONCN

— o

oo

oo

—

CN(N

— o

^-.

— o

moo

On —

m

—o

CO

oo ^-

CO

2

^s

Po

a

a E

— o

,/

E

c

-ii

;::

mo

o

Tj-

o

m <N

o

-^

v£J

c^

Ov

»n

O

^

o

E u w

o

Z

(N

o

po

^

1^

"^

s

•a

>

o

CJ

Jr

£

u

«

-c

OOCT

r

:

^

°oS

Oo

t^f^

oR

"^O

CT^^/^

vo^

of-^

<^»n

prS

Po

'^O

frg

HO

O

— o

o

OJ

":

o

o

Oo

— o

—

SiT!

Po

Oo

O

ts

'^

o

o

— OS

2o

—

O

go—

o g^

P o

S2o

:

Sox

Sf^

Oo

U

n<^

^O

S<^

Oo

**

"".

.

p:

P o

OS

r^ Co"

~ o

f:^

"".

O

So

Po

-:

o

~o

qj

'S-

~:

o

" o

ii-S^

M

—o

oo

o

U

^o

Po

>o

o

(S o

—

po

CJ

—

^

Po

'

o

o cs

o

CsJ

CN

>

— o

P O

^

OS

O^

PO

>n Co

o

U

Po

^' oo

»*

J.

Po

OO ^OO so

—o

Po

^

o o

OS f^

V~i

P o

as

OS

^-'

S2

Po

O

CN

in t^

oo

CQ

"^

U

P o

Po

Po

p o

Po

~;

o

Po

P O

P o

°o

P o

M Co

^

po

o

5

P

So

po

S--3

u

>•

-2o

3

-:

S

S'

p o

—

—

:

So

Po

S'

o

o

Po

p)

en

eg-

P o

o

iji

p

P o

S-

£

CSS

-J

ws

D

Z

c=

-a -a

&

§ i

o

o

^

o

£

^

=

2o

Po

-c

"o

Po

—

P o

"^

?°

SI"

PS

"S S^

P8

P o

.g

g

H

to

"a

<U

5 " S

c

1

3 5

c5

IK

^

CN

o S

s

3 ^

o

PO

:

Po

t~ o

Po

P o

rn oo

P o

P o

U 3 ^

i3

u

S

~o

Po

-3 •=

Po

a

p E

Po

= s s

o [^

U a

o w v.

c 60 C/1

u.

^

OC

.o

-S s

^

^

^3

_

'r7

c^

rt

ca

^ u

3

"rt

C

c

1-^

£i

5

-a

C3

uT

^

g s

i

is

.2?

'5

.70

.

65

.

60

0.55-

0.50w

u

m

0.45

•-1

0.401

u

o

^ 0.35

o

Q

0.30-

§0.25

4-)

U

n3

fc

.20

.

.

15

10

0.05-

.

00

'

'

'

'

'

'

I

I

1

82

'

'

'

'

I

'

I

I

83

84

'

'

'

'

I

'

'

'

85

Region of Residence

Figure

1.

'

I

37

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

I

'

I

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

Year

Gaza

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

I

I

95

96

West Bank

Fraction of employed working in Israel by region

Ji^

0.85-

.

80

CO

Pi

c

o

a,

°

0.75

o

QJ

e

>,

o

j—i

a

e

w

.

.

70

65

'

'

I

1

82

'

I

'

i

I

83

84

85

,

I

I

1

I

I

I

86

87

Region of Residence

Figure

2.

Employment rate by region

'

'

88

89

Year

Gaza

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

I

I

I

I

I

I

90

91

92

93

94

95

'

'

I

96

West Bank

c^^S

{

0.10-

.

09

.

08

07

.

0)

>i

o

1—

ex

%

0.06

Q)

U

>-l

O

05

.

O

(0

04

.

o

u

03

.

.

02

0.01-

.

00

Region of Residence

Figure

3

.

Unemployment rate by region

Year

Gaza

West Bank

iL

24

22

20

T3

O

16

-

14

-

CO

Q

12

10

'

'

'

I

'

'

'

I

81

82

'

'

'

'

I

83

'

'

'

'

I

84

'

'

I

85

Region of Residence

Figure

4.

1

I

I

I

I

'

'

I

I

6

87

88

89

Year

Gaza

Average days worked by region

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

I

I

I

I

I

90

91

92

93

94

'

'

'

'

I

95

'

'

'

I

96

West Bank

^7

26

24

22

-

20

-

0)

u

o

16

Q

14

12

-

10

-

'

'

'

I

1

'

'

I

82

'

'

'

'

I

83

'

'

'

'

I

84

'

'

'

'

I

'

85

Work Location

Figure

5.

'

'

'

'

I

86

'

'

'

'

I

87

'

'

I

I

39

Year

Gaza

Jerusalem

Average days worked by work location

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

I

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

XXX

'

'

Israel

West Bank

3.?

1200

1150

/I

1

1100

1050

1000

950

^

900

(0

^

850

(0

QJ

PS

800

750

4-1

G

o

'^

tn

-

700

650

m

u

CD

>

600

<;

550

-

500

450-

400

-

350

-

300-1

81

-T—i—I—r—i—r-

82

83

84

85

16

87

88

89

91

90

92

93

94

95

96

Year

Work Location

Figure

6.

Gaza

Jerusalem

><

X

X

Israel

West Bank

Average monthly wages in 1991 NIS by work location

Male employees aged 18-64

2f

60

55

-

50

-

Q)

(0

S

45

PS

en

en

(0

Q 40

0)

Di

(0

U

QJ

>

35

30

25

I

82

'

'

'

'

I

83

'

'

!''''!'

'

84

85

Work Location

86

—

'

'

'

'

38

7.

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

'

I

I

'

'

'

'

'

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

Year

Gaza

Jerusalem

Figure

I

I

'

I

^—^—^ Israel

West Bank

Average daily wages in 1991 NIS by work location

Male employees aged 18-64

3^