Shifting Urban Priorities: By Francesca Napolitan

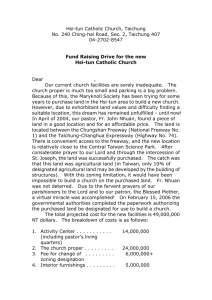

advertisement