A Coordination Theory Approach to

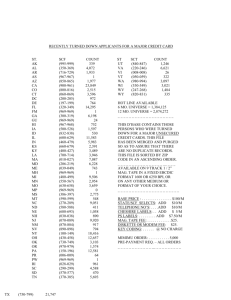

advertisement