Learning Histories: Using Organizational Learning

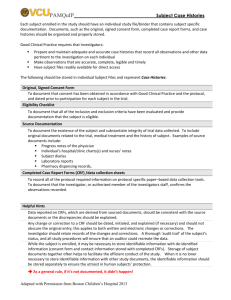

advertisement