Thomas A. Kochan, Casey Ichniowski, David... Craig Olson, George Strauss SWP#: 3886-96-BPS February 1996

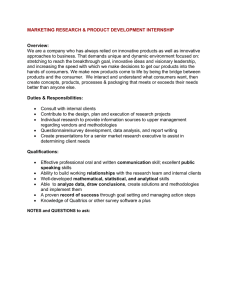

advertisement