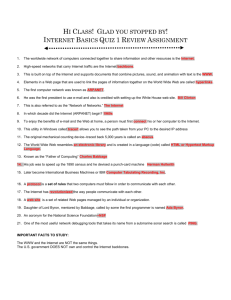

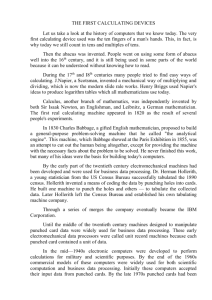

Co-evolution of Information Processing Technology and Use:

advertisement