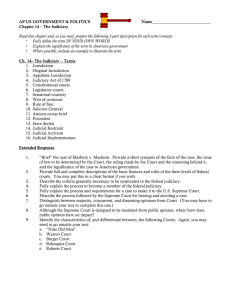

THE RISE OF JUDICIAL POWER IN AUSTRALIA: I INTRODUCTION

advertisement