The Csang6 in Boundary and Ethnic Definition in Transylvania by

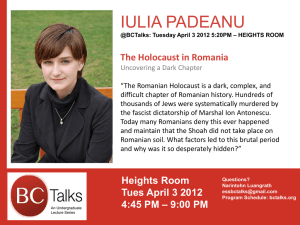

advertisement