Document 11237050

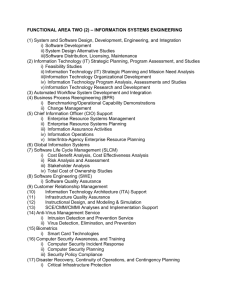

advertisement