Where to read more 70 •

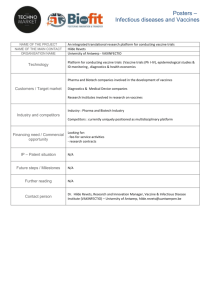

advertisement