T ree Guide Community

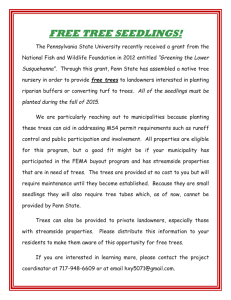

advertisement