.—. ; ; o

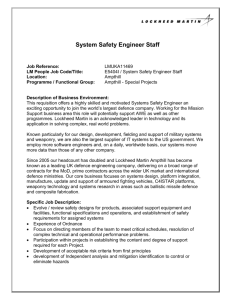

advertisement