(c) crown copyright Catalogue Reference:CAB/24/181 Image Reference:0003

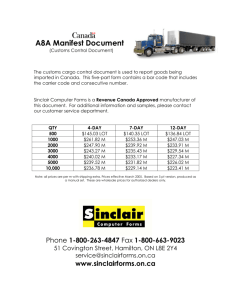

advertisement